A positive betrayal

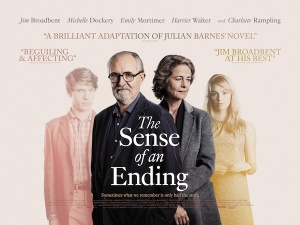

by Mark Reynolds “On one hand it’s a psychological thriller, so people read it fairly quickly. On the other hand, it’s a novel that withholds things from you,” says Julian Barnes of his Man Booker Prize-winning The Sense of an Ending. In the thoughtfully crafted new film version, that withholding remains vital to the slow-burn reveal, but a major hurdle in adapting the book was to flesh out supporting characters beyond the restricted and wilfully imprecise viewpoint of its less-than-reliable narrator Tony Webster (Jim Broadbent).

“On one hand it’s a psychological thriller, so people read it fairly quickly. On the other hand, it’s a novel that withholds things from you,” says Julian Barnes of his Man Booker Prize-winning The Sense of an Ending. In the thoughtfully crafted new film version, that withholding remains vital to the slow-burn reveal, but a major hurdle in adapting the book was to flesh out supporting characters beyond the restricted and wilfully imprecise viewpoint of its less-than-reliable narrator Tony Webster (Jim Broadbent).

Soon after the book’s release in 2011, playwright Nick Payne (Constellations), in a meeting with production company Origin Pictures, was asked if he’d read anything recently that he’d be keen to adapt. “I assumed the rights would be unavailable, but miraculously they weren’t,” he recalls, so Origin moved swiftly to snap them up.

Ritesh Batra, whose debut feature The Lunchbox picked up the Critics’ Week Viewers’ Choice Award at Cannes 2013, had also loved the book: “I tracked it down a little bit, found out that it was already in development and forgot about it. About a year after that, the producers had seen The Lunchbox and came to me with an offer to direct. I was very curious to see what Nick had done with it. I read the script and obviously fell in love with it.”

Payne and Batra then sat down together to work through a few issues. “We just bounced around the script between us for a while,” says Batra. “It’s nice to work with people who are secure with their talent and just really open.”

The best way to be loyal as a filmmaker is to be disloyal to the book; I’ve always believed that.” – Julian Barnes

Batra was struck by an attack of nervous excitement on meeting Julian Barnes for the first time, but ultimately came away with a thoroughly encouraging endorsement. “We sat down in his garden and I’m sitting there, having tea and cake,” he recalls. “He started saying something to me and went on for a good five minutes and I didn’t hear a single word he said because I’m thinking ‘I’m having tea with Julian Barnes!’ But the last thing he said was ‘go ahead and betray me.’ I’m glad I caught that one.”

“The best way to be loyal as a filmmaker is to be disloyal to the book; I’ve always believed that,” Barnes explains. “As long as you’ve handed it over to highly talented people, you have to let them fly free with it.”

Being given licence to stray from a blow-by-blow retelling of the novel was a huge attraction for Payne. “The thing that really appealed was that you can structurally do something quite playful, just like in the novel,” he says. “The screenplay is almost a coming-of-age story, but about someone who’s in their sixties. Often that genre is reserved for people who are younger, but I think people continue to change their entire life.”

Of course Batra and Payne wanted to stay faithful to the essence of the book, but they found the need to extrapolate both place and character in ways that may surprise some readers, but certainly add emotional weight.

Tony’s tragic school friend and love rival Adrian, his estranged wife Margaret (Harriet Walter) and their daughter Susie (Michelle Dockery) are given far more influential roles. Freya Mavor, who plays the young Veronica, Tony’s first love, believes this adds greatly to the viewer’s engagement. “What Nick’s done really well,” she says, “is that these characters that are passing by in the book – the daughter, the friends, Margaret – they all become pillars in the script. I think that’s a feat to be able to do that and still remain so true to the book’s essence and feeling.”

Veronica is an enigma in the book since Tony, whose descriptions are all we have to go on, simply can’t work her out. “The Veronica in the book is a tragic figure that really works within the book,” says Batra, “but our Veronica is someone who is full of life, and her life is more interesting than Tony’s.”

Nick Payne was thrilled that Charlotte Rampling was signed up to play the older Veronica. “She’s so experienced that she can convey an awful lot through doing very little,” he says. “I think that’s a great thing for Veronica, who isn’t in the story a huge amount but is a vital element. You need someone who can convey an entire history, an entire life that’s been lived while not literally giving any of that away within the scenes.”

“She’s not so mysterious,” observes Rampling, “she’s just somebody that actually lives by her own way of thinking and her own social rules. She has a particular idea of her own individuality. She behaves in the way she wants to behave and feels that it’s appropriate to behave, she doesn’t really think too much about other people’s sensitivities. Veronica’s not necessarily a mystery, but she’s certainly a mystery to a man like Tony.”

The actors relished Batra’s openness to new ideas on set. “The good shooting days are always the ones where you discover something about the characters; more than what you thought you knew,” maintains the director. While Broadbent describes Batra’s approach as “very precise and very detailed, watching every shot and every moment of the action. It’s a comfort as an actor to have someone taking that degree of care. You feel in safe hands.”

“I think he is the perfect person to make a film on English manners,” says Emily Mortimer, who plays Veronica’s mum Sarah in the flashback scenes, “because, like all the best films that have been made about English manners [she cites Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility and Robert Altman’s Gosford Park ], he’s not from here. I think he has a way of seeing through to the heart of what is actually going on and finding humour in the absurdity of the way English people relate to each other that bring it alive and give it a peculiar quality.”

Batra agrees that he had a fascination for understanding the English psyche from the outside. “I think it has to do with the British reserve and how they don’t ever really say what they’re thinking [or] they have strange ways of expressing it. All of the characters have trouble expressing their feelings. It seems to be a quintessential British problem. You just have to keep this sense of discovery alive and make sure the work keeps speaking to you, and you’re sort of talking back to it,” he explains.

The same fluidity applied to the script too, with Batra in constant touch with Payne about the story during filming. “I think I’ve been very lucky in that he wanted to keep me around,” says Payne. “We worked on the script very closely and even changed a few things during shooting.”

Looking back over the whole writing process, he reflects, “I think the bit that really appealed was that it was about memory, but not in a way that film normally is. It’s a kind of everyday memory where everyday people have mythologised retrospectively how badly they treated people.”

“I think we’ve all got stories that we built up in our heads about what actually happened,” adds Rampling, “because Julian Barnes doesn’t really give us any tips. And so it’s up to us, as the actors, to fabricate the story.”

Payne sees a positive in Tony’s conscious choice to face up to a past he had selectively erased from his memory. “He is given the opportunity to look back over his entire life and see it in a completely different way,” he concludes. “I think there’s something quite optimistic about that. History is not infallible; it’s fluid and can change. You never run out of a second chance. The scale of the story is relatively small and it celebrates the ordinary. I hope that you can walk away with a sense of a very particular kind of longing that Tony feels.”

The Sense of an Ending is out now in cinemas nationwide, distributed by StudioCanal.

thesenseofanending.co.uk

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

Read his round-up of April 2017 adaptations and biopics.

@bookanista