A selective objective

by Mark Reynolds This year’s shortlist for the 2017 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award – open to any novelist or short-story writer published in the UK, and at £30,000 the richest prize in the world for short fiction – includes three women and three men, four American writers, one British and one Irish author.

This year’s shortlist for the 2017 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award – open to any novelist or short-story writer published in the UK, and at £30,000 the richest prize in the world for short fiction – includes three women and three men, four American writers, one British and one Irish author.

The US writers are Kathleen Alcott, Bret Anthony Johnston, Victor Lodato and Celeste Ng; the British nominee is novelist and poet Richard Lambert; and Ireland is represented by Sally Rooney, whose forthcoming debut novel Conversations with Friends is creating a huge buzz.

The judging panel consists of Anne Enright, Mark Lawson, Neel Mukherjee, and Rose Tremain, and is chaired once again by Andrew Holgate, Literary Editor of The Sunday Times. The winner will be announced at a gala dinner at Stationers’ Hall in London on Thursday April 27.

A longlist of 14 stories was judged ‘blind’. But since the authors were revealed, did past reputations or the emergence of a bright new talent colour the selection of a ‘best’ six, and will either factor influence the choice of the eventual winner? And how can anyone really choose between stories that vary so widely in style and content? Subjects range from the ethics of reputation management, a lifelong love of horses, and the putative discovery of a lost story by Jorge Luis Borges, to intense autobiographical memory, and charged encounter with an ex-lover, and mysterious cross-generational understandings. Read an extract from each of the shortlisted stories and see if you can pick a favourite.

Half of what Atlee Rouse knows about horses

by Bret Anthony Johnston

© Nina Subin

His daughter’s first horse came from a traveling carnival where children rode him in miserable clockwise circles. He was swaybacked with a patchy coat and split hooves, but Tammy fell for him on the spot and Atlee made a cash deal with the carnie. A lifetime ago, just outside Robstown, Texas. Atlee managed the stables west of town; Laurel, his wife, taught lessons there. He hadn’t brought the trailer – buying a pony hadn’t been on his plate that day – so he drove home slowly, holding the reins through the window, the horse trotting beside the truck. Tammy sat on his back singing made-up songs about cowgirls. She named him Buttons. No telling how long he’d been ridden in circles at the carnival. For the rest of his life, Buttons never once turned left.

A year later, days after Hurricane Celia hit and everyone was digging through soggy debris for ruined photo albums and missing jewelry, an old woman from Corpus called Atlee about a chestnut mare. It wasn’t hers. She’d found the horse standing in her fenced backyard, soaked to the bone and spooked. “I think the storm dropped her here,” she said. He drove out and threw a rope not around the mare’s neck but her hoof, then coaxed her into the trailer with quiet talk and sugar beet. He ran an ad in the paper, hung signs in the feed stores, called every rancher he knew. He named her Celia and she turned out to be as fine a horse as he’d ever seen, smart and sure-footed. No one ever claimed the old girl. Not something he’d been able to parse.

The most beautiful thing he’d ever seen were the wild horses in Arizona. He’d gone to deliver Celia to a couple in Phoenix; they needed a companion horse for an old blue roan that was cribbing and stall-walking. Atlee was going to miss her and that must have been evident because after supper, a ranch hand said he knew something that would cheer him up and they drove out to the Salt River. No one knew how long the herds would survive. The state considered them stray livestock and staged round-ups without notice or due process. But Atlee saw a hundred horses that first evening. He glassed the mesa with the ranch hand’s binoculars and found the animals in the orange dust. They pawed the ground and threw their heads. They clacked their teeth and nipped each other, bucked and gave playful chase. Wind lifted their manes and tails. They bit at each other’s knees and reared up and sniffed the air. When one of the stallions caught a scent, maybe of Atlee himself or the truck or the ranch hand’s cigar, they broke into a run like nothing he’d ever witnessed. The herd spread and gathered, spread and gathered, one tremulous and far-ranging body, until they came together in a gorgeous line, a meridian dividing before and after.

Read on

Every little thing

by Celeste Ng

© Kevin Day Photography

First let me try and explain: it’s like falling into deep, deep water. A sudden plunge that knocks your breath away, and once you go under, you forget which way is up. One minute I’m in line at the bank, or crossing the street, or pushing my cart through the Sav-Mart. Then something trips me and my memory opens up and I tumble in. Maybe I see a barrette in someone’s hair and suddenly I’m six years old, at the Gimbels perfume counter. Eight greasy fingerprints on the plate-glass front. Eleven atomizers on a tray, piano music tinkling through the store stereo. A poppy seed stuck in the saleslady’s front teeth. She turns her head towards Leather Goods and two wisps fly loose from her tortoise-shell clip and my mother slips a bottle of Chanel No. 5 into her pocket and a snail of sweat creeps down my back and she pulls me away by the hand. I live it again, every little thing, and when I come back to the present the teller is shouting Miss? Miss? through the hole in the plexiglass, cars are honking, a quart of ice cream is melting to soup in my hands. On my back the same wet snail-trail. In my nostrils, Chanel No. 5.

You’d think this memory would’ve made me a straight-A student, a Jeopardy champion. You might call it a gift. I wouldn’t. In school, when I opened my locker or sharpened my pencil or sat down with a quiz, I’d suddenly fall into some other day, some other moment. Ten minutes later I’d still be standing there, lock in hand as the late bell rang, or my pencil would be ground down to a nub, or the teacher, gently and sadly, would say, “Brianna, time’s up.” Even now, behind the wheel, I get lost in a memory and find myself parked at the Dairy Queen by the train station, or the hospital where Caitlin was born, or on Route 6 halfway to Chatham, and Caitlin, if she’s in the car, says, “Mom, you have the worst sense of direction.” But I can’t help it. Once I heard a story on the radio about a woman like me. She had scientists baffled. “Hyperthymesia,” they called it: highly superior autobiographical memory. They thought there might be forty or fifty people in the world like us, people whose pasts keep opening up and swallowing us down. I went to a doctor once, myself. I thought he would look at me and just know. But he took my blood pressure and told me to take a vitamin and said I was just fine, and I never told him. I never told anyone.

That’s how I ended up cleaning rooms at the Meadowlark. It’s just one of those little motels that dot every roadway up and down the Cape, nothing fancy, and the pay isn’t much. My mother sighs every time my job comes up. She’s spent all her life cleaning too: thirty-five years across town at Channel 17, dusting the archive rooms, vacuuming the studio and wiping down the desk after the eleven o’clock news. All those years she kept picking the wrong men: they didn’t hit her or try to touch me, but they drank or ran around or slipped bills from her purse or sat in their underwear watching Maury all day. Uncle Tommy, Uncle Jimmy, Uncle Tony, Uncle Robbie: all of them big men with names like little boys, who stayed for a while and made my mother cry and then drifted out of our lives, some on cue, some on their own. She’d wanted more for me, a husband and a house and a job where I had to wear pantyhose. Instead it’s just me and Caitlin, just enough money for rent and food and a movie once a month. But I work at the Meadowlark because there, my memory doesn’t matter. If the sheets are changed ten minutes later, no one cares at all.

So this is what happened last week.

Read on

Reputation management

by Kathleen Alcott

© Michael Leviton

Alice Niemand had been working for the company two years when the young Hasidic man died, and it made her look at her things, the cashmere cardigans and the pebbled bathmats, and consider how she had earned the money to buy them. On a normal day, it was easy enough not to examine: she never went into a workplace, never talked to anyone who did the same job she did, never discussed aloud the clients whose reputations she had repaired, never shook their hands or heard their voices, these lawyers and dentists and PTA mothers with some angry review or mug shot to suppress. The man who was dead – nineteen, a boy really – had been the victim of sexual abuse by the Yeshiva teacher who had been Alice’s client. The boy had claimed to be his victim, she reminded herself, but then came another feeling, lower in her body, which seemed to ask, in the way it roiled: why would anyone claim that?

On the coast of California where the garnet had eroded to make the sand purple, and from a multi-colored veranda in the New Orleans garden district, and in view of children pushing toy boats in the Jardin du Luxembourg, she had reviewed files summarizing lives and careers and misdemeanors, had typed the stiff sentences that financed her comfortable life. Her parents were as impressed by her new place in the world as they were intimidated by the gifts she sent to their sagging split-level home in the middle of the country. What could they do with an iPad that they couldn’t on their computer, the pauses between their thank yous said, what should they put on these asymmetrical walnut serving boards? Would she be visiting sometime? They were sorry to say they did not have the money to make it to New York. It was never mentioned that the cost of the things Alice sent could have easily covered the flights that would put the three of them in a room together.

Alice had bumped from one Craigslist apartment to the next in the years after college, making friends chiefly to learn from them, when to tilt the head in the course of flirtation, how to conduct oneself in an expensive restaurant, never telling anyone about her father’s job ringing up purchases of gas and Snickers, her mother’s meager income selling Mary Kay cosmetics. She had visited the office, a hyper-color portrait of Silicon Valley opulence, for three interviews and a training session. It was her last month in San Francisco and the last hiring period in which the company bothered to meet anyone in person.

A guy on a skateboard had careened down an aisle that separated two rows of desks, clipping the heels of the formal, uncomfortable shoes Alice wore, and she watched as he landed on an L-shaped couch and began to comment on a Ping-Pong game. To the right of a freestanding iron staircase nearby, a man jogging on a treadmill typed on a computer that hovered above it. “Casey prefers the running desk to the standing,” Alice’s tour guide explained, with a satisfied laugh that she understood she was meant to mimic. In the company kitchen, the snack foods, arranged by color, sat up straight on transparent shelving. “There is such a thing,” she heard a departing tour leader say to a group of new IT personnel, “as a free lunch.”

Read on

The hazel twig and the olive tree

by Richard Lambert

A lost story of Jorge Luis Borges1

A lost story of Jorge Luis Borges1

Irving Samuelson, University of Texas, Austin

In January 1935, Jorge Luis Borges lost his job as literary editor of the Saturday supplement of Buenos Aires’ mass-market daily newspaper, Crítica. One month after his departure, the supplement published a piece by a certain Herbert Lock, retelling the story of the adulterous lovers Tristan and Isolde. It has hitherto been believed that copies of this story had not survived. In fact, until now, Borges’ editorship and Lock’s Tristan story had been considered unconnected, despite the compelling arguments this author made in a 1993 article, that showed that Herbert Lock and Jorge Luis Borges were one and the same.2 But now further evidence, refuting the glib malignities of earlier critics, namely a bill of sale from a bookshop in Jerusalem, and an interview with a member of the 1930s Argentine avant garde, have added weight to my earlier arguments and definitively show that a hitherto lost story of Jorge Luis Borges has come to light.

***

The supplement Revista Multicolor, which Borges co-edited with Ulyses Petit de Murat between June 1933 and January 1935, came out in Buenos Aires on a Saturday, a day of the week imprinted upon Borges’ memory, for it was on a Saturday in November 1926 in the Orangery Restaurant of Palermo Park that Borges lost his fiancé Norah Lange to another man.

This was a break so significant that it was the moment to which Borges would allude in that lost, now rediscovered, story of 1935; and it was also the moment which was to dominate the next seventy years of his life. Even once he had made the rediscovery of romantic love in old age, which allowed him finally to step from the shadow of family (he shared a flat with his mother until her death in 1975) to be with the young Maria Kodama, he still lingered over that first loss of Norah Lange.3 So much so that it received the most oblique and final of textual references in his gravestone inscription, a line from a late, intimately autobiographical story, ‘Ulricca’, in which the memory of a lost love is finally redeemed. And thus he closed the circle on that first loss, and revealed too, how far for him the textual and biographical were merged.

The impact, then, of that meeting of Norah and Oliverio Girond, that preposterous, cruel couple (at parties Norah would stand on tables and declaim her poetry, while Oliverio once drove a funeral carriage through Buenos Aires taunting his defeated rival with a papier maché caricature of him) was long-lasting. A photograph records that Saturday when the literary elite of the city gathered in the restaurant in Palermo Park: Borges stands unaware that, though he arrived at the lunch with his girlfriend, he was to depart alone.

Read on

1 This paper was rejected by Modern Fiction Studies. The anonymous referee, to whom I would dedicate this article were it not that he has chosen to remain nameless and that any dedication, where Borges is concerned, is owed to absence, concluded his report with characteristic cruelty: ‘notwithstanding the author’s shrill protests, this story never existed.’

2 I. Samuelson, ‘A Lost Story of Jorge Luis Borges’, Hispanic Review, 44 (1993), 234–47.

3 The household was strange: even as an old man Borges informed his mother of all his movements and each night before going to bed, would receive two sweets from the family maid like a little boy.

Mr Salary

by Sally Rooney

This extract no longer available here, but you can read the story in full on the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award website.

Read on

The tenant

by Victor Lodato

© Nancy Crampton

When Marie saw the small house, nestled almost invisibly among weedy hills and sycamores, she thought, jackpot. She thought, heaven.

Hell, she thought, I could live and die here.

Of course, all she said to the McGregors was, ‘It’ll do.’

The McGregors owned the property and lived in the large house next door – though next door was a relative term; the main house was at least a hundred yards away. Through the trees all Marie could see of it was a patch of pale blue siding – which, in the right mood, she could easily pretend was part of the sky.

The right mood was not uncommon lately. It often involved gin. Marie was careful not to put the empties in the recycling bin. She didn’t wish to give the McGregors the wrong idea.

Luckily they hadn’t asked her to fill out one of those renter-information packets, or done a credit check. They’d been satisfied with her offer to pay the first six months in advance.

As soon as Marie signed the lease, she felt a weight lifted from her heart. Maybe this lightness had something to do with the land and the trees, which reminded her of the estate she’d grown up on, across the valley, in the Rincons.

Not that she’d been particularly happy there – but it was childhood and so, at a certain age, revered. And certainly it hadn’t been terrible. Her parents had been decent people – though they’d had their edges, their sorrows. Their moods had oppressed her as a child, but now she saw it as a good sign, a sign that perhaps they’d wanted more than what they’d had. When they died five years ago on the highway, it had been their first trip out of Tucson in twenty years. They were going to Apache County to see the ruins, but made it only as far as Pinetop. A sleep-deprived trucker carrying a load of frozen fruit had swerved and toppled.

‘Blueberries everywhere,’ one witness had said.

The caskets had been closed.

Read on

About the authors

Bret Anthony-Johnston is the author of the internationally bestselling novel Remember Me Like This, which was featured on BBC4’s Book at Bedtime series, was named a Notable Book of the Year by The New York Times Book Review, and is being made into a major film. He also wrote the multi-award-winning short-story collection Corpus Christi, which was named a Best Book of the Year by the Independent and the Irish Times, and was shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Fiction Prize. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he has received awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Book Foundation, the Pushcart Prize, the Virginia Quarterly Review and elsewhere. He is the Director of Creative Writing at Harvard University and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

bretanthonyjohnston.com

Celeste Ng is the author of the novel Everything I Never Told You (Little, Brown), which was a New York Times bestseller, a New York Times Notable Book of 2014, was named a best book of the year by over a dozen US publications, and has been translated into over twenty languages. She has also been awarded the Pushcart Prize, the Hopwood Award, and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her second novel, Little Fires Everywhere, will be published bt Little, Brown in September 2017. Celeste grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Shaker Heights, Ohio. She has taught writing at the University of Michigan and Grub Street in Boston and currently lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts with her husband and son.

celesteng.com

@pronounced_ing

Kathleen Alcott, born in 1988 and raised by two journalists, is the author of the novels The Dangers of Proximal Alphabets and Infinite Home, the first of which was published in the US when she was twenty-three. Infinite Home, released in 2015, was nominated for The Kirkus Prize and shortlisted for The Chautuaqua Prize. Her journalism has appeared in the Guardian, The New York Times, The New Yorker and elsewhere, and her short fiction has been listed as notable by The Best American Short Stories. A native of Northern California, she divides her time between there and New York City, where she serves as an adjunct professor at Columbia University.

kathleenalcott.com

@KathleenAlcott

Sally Rooney © Jonny L. Davies

Richard Lambert is a poet and novelist, and a graduate of the MA in Creative Writing at UEA. His poetry collection Night Journey was published in 2012 and he is the recipient of an Arts Council award to write a new collection, The Nameless Places. Individual poems have appeared in The Spectator, the TLS, Poetry Review, Poetry Ireland Review, PN Review, The Rialto, and The Forward Anthology 2014. His novel The Wolf Road was longlisted for the 2017 Caledonia Novel Award for unpublished debut novelists and he is currently on Escalator, a talent development scheme for writers in the east of England. He has a PhD in medieval history from the University of Bristol and has worked in higher education, local government and the NHS. He lives in Norwich.

eyewearpublishing.com

Sally Rooney was born in the west of Ireland in 1991. She lives and works in Dublin, where she graduated from Trinity College with a BA in English Literature and an MPhil in Literatures of the Americas. Her work has appeared in Granta, The White Review, The Dublin Review, Winter Papers and The Stinging Fly. Her debut novel, Conversations with Friends, is published by Faber & Faber in June 2017 and forthcoming in twelve territories worldwide.

@sallyrooney

Victor Lodato was born in New Jersey. His novel Mathilda Savitch (2009), was hailed by The New York Times as “a Salingeresque wonder of a first novel” and was a best book of the year in Christian Science Monitor, Booklist and The Globe & Mail. The novel won the PEN USA Award for Fiction and the Barnes & Noble Discover Prize, and has been published in sixteen countries, including the UK (Fourth Estate). Victor is a Guggenheim Fellow, as well as the recipient of fellowships from The National Endowment for the Arts, The Camargo Foundation (France), and The Bogliasco Foundation (Italy). His short fiction and essays have been published in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Granta and Best American Short Stories. His latest novel Edgar and Lucy is published by St Martin’s Press. He currently divides his time between Tucson, Arizona and Ashland, Oregon.

victorlodato.com

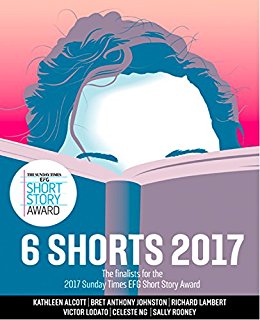

The six shortlisted stories are published together in a Kindle Edition as Six Shorts 2017, £1.99. Read more.

The six shortlisted stories are published together in a Kindle Edition as Six Shorts 2017, £1.99. Read more.

shortstoryaward.co.uk

@ShortStoryAward

#STEFG

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

Postscript

The 2017 Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award was won by Bret Anthony Johnston. Read our interview with him moments after he accepted the prize here.