Bret Anthony Johnston: Tricks at the top

by Mark ReynoldsBret Anthony Johnston has won the Sunday Times EFG Short Story Award with his story ‘Half of What Atlee Rouse Knows About Horses’, a touching meditation on memory and loss that weaves together significant moments from the life of an 80-year-old Texan through the prism of the three great loves of his life: his wife, his daughter, and horses. I caught up with him moments after he accepted the prize at a gala dinner at London’s Stationers’ Hall.

MR: How does it feel to be the winner? And do you have a few words for the other shortlisted writers?

BAJ: I feel immense humility and gratitude – and a deep conviction that this is a mistake. The other writers’ stories set the bar so high in terms of the way each one reinvented the short story. The level of imagination, the level of empathy, the abiding lack of judgement in all of the stories feels to me like a new standard, and I’m a better writer for having read them. In many ways I feel that just being introduced to these particular stories was in itself a victory.

The story is written in fragmentary vignettes, which you accumulated over almost a decade, reworking and re-sequencing them over time. Do you often write in this way? And what did that approach bring to this story?

I’ve never written in this way before. My friends and family have heard me for many, many years calling this ‘the weird horse story’: you know, “I worked a little more on the weird horse story today”; “I wrote another thing for the weird horse story.” I didn’t even think of it as a complete story until very nearly the end, it just kept finding its form and surprising me in the directions it would take itself. I’d spread the story out on my office floor, and I would look to see not just how many long vignettes were up against a short vignette, it was more of a sense of how would this man feel the memories moving through his consciousness? The structure that it was published in was not the structure it had in the draft before; it was constantly in flux, and then in the final version it did feel as though there was a kind of integrity and intuitiveness with which it was moving from beginning to end.

The wife and daughter come in and out of focus throughout the story, but they are always the filter through which his memories are flowing.”

Because of the nature of memory, you could’ve sequenced it in many ways. So how did you come to the final sequence?

On its surface this seems like a story about horses. I ultimately realised that this is a story about a man looking back on his life through the lens of his wife and his daughter. The story begins with an anecdote that has both his wife and daughter in it, and that became the organising principle. The wife and daughter come in and out of focus throughout the story, but they are always the filter through which his memories are flowing. And it was only in the last iteration that it seemed to cohere in a way that made not a logical sense but an intuitive sense.

You mentioned in your acceptance speech the work that the editors at American Short Fiction did to help shape it. What did that entail?

They had a very soft touch on the story, but a significant one. When I got the manuscript back from them with their questions and comments, I remember thinking they understood the story better than I did, and I don’t know that you could ask for more out of a relationship with an editor. So they made the story better than it should’ve been.

How many of the themes of failing memory, love, death, illness, danger, survival, and the shared stories that bind a family and a marriage were present when you first had a glimpse of Atlee?

None of it. They emerged as I wrote more and more vignettes, and I started to understand how they were related to each other. In many of the vignettes that I wrote early on, there was no Atlee, it was completely disembodied, and it was only years into it that this character started crystallising and I understood that these were his memories, even if he were not in the memory itself. So it was very much a process of discovery and surprise that led me here. I had no idea what I was doing. I’m not in any way being coy or disingenuous; not only did I never think this story would be published, always thinking of it as this weird horse story, I also didn’t ever really think it was going to be a story. It was just something I was doing while I was working on the real stories, the real novel. So clearly I’ve been doing it wrong for so many years, and I finally got lucky!

What keeps drawing you back to Texas as a landscape for your stories?

What keeps drawing you back to Texas as a landscape for your stories?

Texas is a place that I know very well, but I feel like a stranger there. I just happen to know the map very well – the geographical map, the emotional map, the cultural map – and yet when I go back there I find myself in the role of witness.

What’s the latest on the film adaptation of Remember Me Like This?

The goal as I understand it is for them to begin filming by the beginning of the fall. I have nothing to do with the film except that I’m a very big fan of the script, and of everybody who is involved in it, and I’m very, very hopeful, because I think they’re putting together something special. All the information I’m getting is second-hand, but I believe they want to start shooting at the beginning of the fall because Rosamund Pike is going to star in it, and that’s the time that works best for her. The director is Vadim Perelman, who adapted the Andre Dubus III novel The House of Sand and Fog. He optioned the book, and the team that is doing it just seems like a dream team to me.

I think skateboarders look at the world in a different way, in the same way that writers and artists do, and what they notice defines who they are.”

I believe you’re the first ex-professional skateboarder to win this prize. Tell me a little about that passion.

Yiyun Li is a very competent skateboarder! It’s more accurate to say that for thirty years I have been a very, very serious skateboarder. I toured the country on a professional team, and skateboarding is one of the loves of my life. It’s as much a part of my identity as being a writer, and the two far more similar than one would immediately think. I think skateboarders look at the world in a different way, in the same way that writers and artists do, and what they notice defines who they are. What a writer notices defines what kind of writer he or she is. I think the other blatant similarity between skateboarding and writing is that they both depend on an inhuman patience, an inhuman resilience, that you are just going to work at something until either it breaks you or you break through. I couldn’t be happier that I won tonight, and I couldn’t be more shocked. Had it not gone my way, which it very easily might not have, I would’ve still thought, well, that doesn’t feel so great but it doesn’t feel as bad as falling to the bottom of a drained pool when I’m trying to do a trick at the top. But with both of these things, you just pick yourself up and go back to work.

On your creative writing course at Harvard, which short-story writers do you compel your students to read first, if they haven’t already encountered them?

It really depends on the student. There are certainly many, many stories that I think everybody should read, but as I get to know the students I try to tailor the reading list toward their visions and their voices. But to answer the question broadly, I have them read Chekhov, I have them read Amy Hempel, I have them read Jamaica Kincaid, I have them read Ethan Canin, the list goes on and on. I want to introduce them to work that is going to make them want to write. What’s going to inspire them? Who are the writers that are going to move them to emulation? That’s what I’m trying to understand. Sometimes I will have them read someone like Alice Munro or William Trevor, but I always do it with a caveat of “don’t try this at home”. You don’t want to take on Alice Munro…

In your speech you gave Vanessa Furse Jackson a shout-out as an inspiring writing teacher. Who were your other tutors at Iowa, and what were the best pieces of advice or encouragement you received?

I’ve had a number of great teachers over the years. At Iowa I worked with Frank Conroy, Marilynne Robinson, Chris Offut, Ethan Canin, James Alan McPherson, and I had many great pieces of advice. The first thing that comes to my mind is Frank saying that you need to establish a routine as a writer, because the routine is going to make it easier and easier day by day to reach the level of deep concentration that you need to do this work. So I suppose that if you have the choice between working seven hours on Saturday or working one hour every day of the week, work every day of the week for one hour because your work on Monday is going to be very hard and very foreign and frustrating. On Tuesday, because you’ve logged an hour on Monday it’s going to be just a little bit easier. On Wednesday it’s going to be even easier, because you’re conditioning yourself to come back to this level of imagination and concentration. And that advice has stuck with me.

“Johnston showed brilliance over the long distance in his novel, Remember Me Like This, and now proves equally adept at brevity.” Mark Lawson

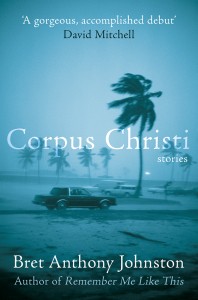

Bret Anthony Johnston is the author of the internationally bestselling novel Remember Me Like This, and wrote the acclaimed documentary Waiting for Lightning, about extreme skateboarder Danny Way. Previously shortlisted for the Frank O’Connor International Short Fiction Prize for his story collection Corpus Christi (Random House, 2005; Two Roads, 2015) he has received awards from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Book Foundation, the Pushcart Prize and the Virginia Quarterly Review. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, he is Director of Creative Writing at Harvard University and lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Read more.

bretanthonyjohnston.com

shortstoryaward.co.uk

@ShortStoryAward

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

Read ‘Half of What Atlee Rouse Knows About Horses’ and the other shortlisted stories:

shortstoryaward.co.uk/shortlists/2017