Procedures

by Laidi Fernández de Juan

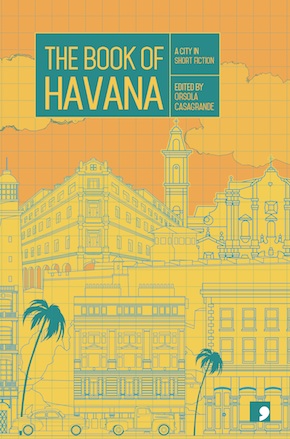

“A collection that’s saturated with the sights and smells of Havana… to show you the reality of the city in all its glory and squalor.” Indie Lit Fic

Maria E never knew anyone to quit smoking without claiming that they’d been on three packs a day until just the day before. Nor did she know anyone to have their appendix removed without saying the surgeon claimed that if they’d arrived three minutes later, it would have burst and caused fatal peritonitis. Similarly, she had never heard a single story about red tape genuinely being reduced in her country, even though the programme of ‘de-bureaucratisation’ was announced with great fanfare.

“Something had to be true,” she told herself, “some mechanism had to be weakening the chains.”

This was the only explanation she could think of for why the newspapers kept talking about the willingness of the state to reduce formalities in the legal apparatus, even though Maria E had never seen a single, concrete example of it. This was why, after three years of procrastination on her part – not unlike the three packs of cigarettes and the three critical minutes between life and death – she resolved to contribute to the regulation of the city by registering, as legal property, the house in which three generations of her family had been living, ever since the year she was born.

“Three things Peru doesn’t have, but Havana does: El Morro, La Cabaña, and a lover like you,” the residents of Havana used to say when they were kids, happy to live without an identity card or a mobile phone, let alone property. At that age, no one seemed to worry about material things. The enlightenment of poverty made everyone part of the same family, which in turn made the major transitions in life, from one stage to another, all the more bearable, being free of needing to rush from office to office trying to authenticate the status of ‘owner’. As Maria E still had the unfinished business of ‘House Registration’ to see to, she took advantage of her early, voluntary retirement, and dedicated herself to the task – just at that moment when rumours started circulating through the streets of Havana that citizens would be relieved of this unforgiving and (as the practice showed) outdated legal process.

Three documents were needed to start the endlessly postponed marathon of recording the fact that her family was the owner of the Havana building where her kids had been born and learned to walk, and where she herself had opened her eyes for only the second time, on returning from the clinic where her mother had given birth to her, in this city they once called ‘Courtesan of the Sun’.1 A yellow certificate awarded to her grandmother – now deceased – congratulating her on being the owner of the house, was the first of the three essential papers. An application to confirm such ownership, made three years earlier, came second in line of importance. And finally, a notary’s witnessing of her signature – granting her authority to deal with all things pertaining to registration, legalisation, authentication, and whatever other convolutions might come her way – conferred on Maria E the necessary legal power to face, with joy and enthusiasm, these apparently streamlined procedures.

Even though the office didn’t have any seats, it was still a nice place to wait. The grass outside where hopeful applicants could sit wasn’t too itchy, the air wasn’t unbearably humid and the dog shit was easily avoided.”

According to the information she was given, her first task was to commission a plan of the house from a specialist experienced in such matters, outlining the house’s perimeter and the property boundaries. This first step wasn’t hugely inconvenient, it had to be said. Even though the damn office where you could wait for an appointment with one of these specialists – known as ‘Community Architects’ – didn’t have any seats, it was still a nice place to wait. The grass outside where hopeful applicants could sit wasn’t too itchy, the air wasn’t unbearably humid and the dog shit was easily avoided. Although one of several signs on the door announced that contracts must be signed at 9am sharp, as is natural in Havana, nobody turns up before 10. This makes for some pleasant ‘Vedadenese’ conversation among the applicants (‘El Vedado’ being Maria E’s neighbourhood), so that when people finally get served, no one is too surprised by the details that get shouted between the architect and his poor client – for what looks like the lobby to the office is actually the only place you can explain to anyone what is needed. The presence of everything outside of the lobby – the lawn, the front door covered in information posters, the staircase leading upwards, and the tiny room beyond – all seem superfluous to it. This was more an impersonation of an office than an actual one. But who cares about such details in Havana, let alone in El Vedado?

Maria E was eventually seen by an architect the same age as her son. A very friendly guy; confronted by her surprise at the lack of privacy (at the start of the procedure she was astonished, and showed it), he led her away by the hand and they resumed the meeting in a closet next to the door that served as an information wall. Suppressing her tendency for claustrophobia, Maria E found the courage to express her determination to legalise the only space she’d known as ‘home’ since she was born in El Vedado – that once aristocratic neighbourhood now showing all the signs of falling into ruin. Mercifully, this charming little boy, once he had taken off his barely noticeable earphones, explained the various steps she needed to take next. Going to the offices of UMIV would be her first step and then, after he had drawn up a plan of the house, she would need to register it at the Land Registry office, once any mistakes had been first corrected at a public notary’s office. In other words, three more steps to go.

Not one for asking lots of questions, Maria E wrote everything down in a notebook she had already labelled ‘Procedures’ and, immediately after the meeting, brimming with energy, headed to what they call UMIV, the Unidad Municipal de Inversiones de la Vivienda2, several blocks away. Its whereabouts had been explained to her by a man who’d been her companion on the grass, among the dog shit, earlier that morning. Around mid-afternoon, having waited over three hours sitting on a stair that sagged rather comfortably in the middle, she was attended by a UMIV lady the age of her mother, who was kind enough to explain to her that her job was to confirm the number of each house. Despite the fact that our protagonist presented the lady with papers proving her Vedado house number had been set into the doorframe before the famous cyclone of 1926, the woman insisted she needed at least one more month to verify this, because in order to ensure this number was the correct one (which needed to be done before the architect could draw up his map with perimeter and boundaries included), she would need to draw up a different map first – of the block surrounding her house. In other words, she would have to visit the whole of El Vedado, draw a schemata of the house’s surroundings, measure whatever was measurable from the asphalt of the street to the front door, and then and only then, determine that indeed the number provided was the correct one. Or not.

Six weeks later the same woman, the age of her mother, asked Maria E to return to the office that she shared – as is the tradition in Havana, even more so in El Vedado – with other UMIV officials. Little to her surprise (her astonishment was fading fast by this point), the woman informed her that, even though her house number was indeed correct, from then on, they would have to add a letter to the end of the number. In their case, the capital A. The lady smiled as she listened to Maria’s objection that there was no B nor C near her house, so it didn’t make sense to add an A. She smiled at our heroine, and replied enigmatically, “One day you’ll understand.”

1.Credited to Jorge Mañach (1898–1961); a Cuban journalist, philosopher, essayist and biographer of José Martí.

2. The Local Housing Investment Office

From ‘The Trinity of Havana’ in The Book of Havana (Comma Press, £9.99)

Laidi Fernández de Juan was born in Havana in 1961. A writer and doctor, she has worked many years in Cuban medical missions, especially in Africa. She began her literary career in 1994 with a collection of short stories, Dolly y otros cuentos africanos (Letras Cubanas, 1994) and has now published ten books. She writes a regular column in the literary magazine Cuba Contemporánea and for the online magazine La Jiribilla. The Book of Havana, edited and with an introduction by Orsola Casagrande, translated by Orsola Casagrande and Séamas Carraher, is published in paperback by Comma Press.

Laidi Fernández de Juan was born in Havana in 1961. A writer and doctor, she has worked many years in Cuban medical missions, especially in Africa. She began her literary career in 1994 with a collection of short stories, Dolly y otros cuentos africanos (Letras Cubanas, 1994) and has now published ten books. She writes a regular column in the literary magazine Cuba Contemporánea and for the online magazine La Jiribilla. The Book of Havana, edited and with an introduction by Orsola Casagrande, translated by Orsola Casagrande and Séamas Carraher, is published in paperback by Comma Press.

Read more

@commapress

Orsola Casagrande was a journalist with the daily national Italian paper il manifesto for 25 years. She is currently co-editor of the web magazine Global Rights, is fluent in Italian, English, Spanish and Turkish, and reads and speaks Kurdish. She currently lives in Havana. Her translations into Italian include works by Gerry Adams, Ronan Bennett and Robert Newman. She is also the author of several non-fiction books and a writer and co-director of documentary films.

Séamas Carraher is a writer, poet and freelance translator who has also worked as a filmmaker. He is currently supporting long-term homeless street drinkers at night to pay the rent, having been a community activist for over 30 years. Orsola and Séamas have worked together for a number of years translating, writing and publishing in a variety of journals and literary reviews, in both English and Spanish, as well as for Global Rights.

globalrights.info