A proposition

by Meryem AlaouiThat’s when she arrives. A skinny stick slides her head through the curtain and opens it with a fluid movement. A skinny stick with long disheveled hair at the end. Hamid told me she was the neighbor’s niece but I hadn’t imagined she would be so young. She’s standing in front of the door and she’s looking at us and smiling. Toothy grin. Horse’s mouth! I look at her. She keeps smiling. I want to laugh. I had imagined her like Nassima el Hor[1]: pale, well padded, well dressed, coiffed, makeup done, put together. And a bit younger, of course; but at least a real journalist!

Instead, standing in front of me is a broom with its bristles dyed brown. She is so skinny that I’m afraid she’s going to snap in two.

—

There are a good dozen bottles in front of us. And the butts of Camels and Marvels intertwined in the ashes. This girl is crazy. I underestimated her, based on her mosquito size. But she can hold her alcohol.

She told me some of her life story and a lot about the film she’s working on. I didn’t catch everything, but the important part is that she left for the Netherlands when she was three and she’s lived over there ever since. She comes back to Morocco every summer. Now, she’s going to produce the film between the Netherlands and Morocco. It’s the story of a girl who earns her living as a prostitute. The girl, whom she hasn’t named yet – but she’s deciding between Jamila and Hasna – meets a man. They hit it off and get together, more or less.

They rob a jewelry store. And after they succeed, he rolls in the dough and takes off. And at the end there’s a twist that I don’t fully understand. And I don’t remember anymore who comes out on top. A story like any other.

And she just wants to chat with me so I’ll tell her what my life is like. That’s all. And she has a small budget for it, but first and foremost, she wants to know what I think about it.

“About what?”

“About what I told you. The film, the story… Everything, really.”

“It’s good. It seems good to me. I don’t know.”

“Could it happen in real life? Could a girl fall in love with a guy and find herself robbing a jewelry store with him? Could she be scammed like that? What do you think? I don’t know if it could really happen that way.”

“…”

This girl might be crazy. She gathers her hair in a long ponytail at the top of her head. Some strands fall to the side.

I don’t know why she’s bothering with these questions. If you want to make a film, make a film and be done with it. She continues, “I’m also trying to imagine the ambiance. It would be filmed in my aunt’s neighborhood. Next to the market, with the setting exactly the way it is. Maybe we’ll change a few things, but we wouldn’t touch the trash. Did you see how bustling it is over there? Hang on, I’m going to get another beer.”

She weaves between the bin-ou-bin[2] boys and comes back with the beers.

“Okay, you know what, in any case, we have time. We’ll talk about it another day.”

Honestly, she makes my head spin.

Why does she want everything to be as it is in real life? Why does she think people watch movies? To see the nasty reality or to get a change of pace and have a laugh?”

We stayed in the bar until they kicked us out. It must have been one in the morning. I don’t know how many Spéciales we downed, but by the end beers covered the table.

Now, we’re sitting in the car staring at the water. You can’t tell where the sky ends and the sea begins. It’s more distinct between the water and the sand. The waves, when they break, form huge braids of white wool. My nose is full of the smell of the sea. And I’m so drunk that I’m not even dizzy anymore.

Leaving the bar, Horse Mouth didn’t take the road through the neighborhood. She turned left. I don’t care. I’ve had so much to drink that I could go to Tangier if she wanted. She drove until we arrived at the corniche. There was almost no one in the streets. When we arrived, we drove slowly, looking at the seaside as we worked our way down the coast, until we reached Sidi Abderrahmane, directly across from the island.

We’re not talking right now, but when we were at the bar, she talked a lot. I couldn’t understand everything she said.

Basically, she came to Morocco to finish writing her story and to find locations to shoot. Now she’ll return to the Netherlands to look for money from a producer to make the film. That part, for example, I didn’t really understand.

If she doesn’t have money, how is she going to make her film? And how has she almost finished writing it? And why does she want to keep the Casa streets as they are, why does she want everything to be as it is in real life? Why does she think people watch movies? To see the nasty reality or to get a change of pace and have a laugh?

Maybe it’s the weed that’s put those ideas in her head.

At the bar, while I was eating, I know she got up to smoke a few joints. She must have had two or three over the course of the night. When she came back her eyes were a bit glassy, completely calm. I know that look.

Also, she has a smoker’s hands. Skinny and dark and a bit yellow at the tips. Now, she’s just rolled another. The first one she’s had in front of me. She hands it to me to light it.

“No, I don’t smoke.”

“You don’t like it?” she says, lighting it and taking a long drag, her eyes half-closed, head slightly tilted back.

“I have a bad history with hashish. It’s a long story,” I tell her, seeing my husband’s face in front of me.

“Mmmh…” she says, taking a puff.

I don’t know if it’s because the hashish is good or if it’s in response to what I said. But I don’t care. It’s nice out, the drive was cool, and I feel good. We don’t have music in the car. There’s a radio but the FM button spins and spins. There’s only the CD player, which works, but she doesn’t have any CDs, she says.

“Next time, I’ll bring Nass El Ghiwane.[3] Do you like them?”

“I don’t know them. Is it chaabi[4]?”

“No. When you listen, you’ll tell me if you like it. What kind of music do you like?”

Without thinking, I respond, “Najat Aatabou, do you know her?”

“Who doesn’t know Najat Aatabou?”

She takes another drag and looks at the water. I light a cigarette.

When I think about it, in the end, I barely spoke that night. We ate, we drank, we drove. We talked a bit about Hamid. The neighborhood. And that’s it. Leaving the bar, she took my number and asked if there was a good time for her to call me.

Then, she asked me to reflect on the film and whether I wanted to work with her or not. She also said that if I were to accept, we would talk about the money later.

And then she drove us here. That’s all.

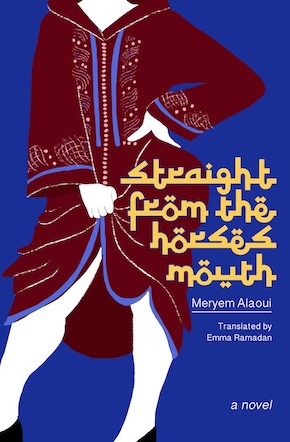

from Straight from the Horse’s Mouth (Other Press, £14.99)

[1] Famous host of discussion shows about social issues. Because of her great empathy for those in the lower classes, many of them consider her the quintessence of journalism.

[2] “Between two.”

[3] A legendary Moroccan musical group popular in the 1970s for their political and poetic lyrics, as well as their revolutionary rhythms. Martin Scorsese once called them ‘the Rolling Stones of Africa’.

[4] Literally, ‘folk’: used to describe folk music.

Meryem Alaoui was born and raised in Morocco, where she managed an independent media group that combined publications in French (TelQuel) and Arabic (Nichane). After several years in New York, she now lives in Morocco. Straight from the Horse’s Mouth, her debut novel, is published by Other Press, translated by Emma Ramadan.

Meryem Alaoui was born and raised in Morocco, where she managed an independent media group that combined publications in French (TelQuel) and Arabic (Nichane). After several years in New York, she now lives in Morocco. Straight from the Horse’s Mouth, her debut novel, is published by Other Press, translated by Emma Ramadan.

Read more

@otherpress

Buy from bookdepository.com

Author portrait © Francesca Mantovani/Gallimard

Emma Ramadan is a literary translator based in Providence, Rhode Island, where she co-owns Riffraff bookstore and bar. She is the recipient of an NEA Translation Fellowship, a PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant, a Fulbright, and the 2018 Albertine Prize. Her translations include Sphinx and Not One Day by Anne Garréta, Pretty Things by Virginie Despentes, The Shutters by Ahmed Bouanani, and Me & Other Writing by Marguerite Duras.

emmaramadan.com

@EmKateRam