Bees can teach us a great deal – but what?

by Lotte Möller

“A fine balance of knowledge and humour on a high level.” Weekendavisen

From antiquity and until very recently bees were likened to exemplary subjects in a perfect monarchy. It was taken for granted that they were ruled by a king because Aristotle had said so in the fourth century B.C.E. and his word – not just about bees but almost everything else as well – would remain the truth for nearly two thousand years.

The Catholic Church has frequently referred to bees and the bee colony as a paradigm for the faithful. Saint Anthony wrote in the thirteenth century that “Christ Our King flew to us from the beehive, which is the breast of the Father. We should flock to him as bees follow their monarch.” In the Revelations of Saint Birgitta of Sweden, bees crop up on numerous occasions. The nineteenth chapter of the second book contains the following passage: “I am God, the Creator of all things; I am the owner and the lord of the bees. Out of my ardent love and by my blood I founded my beehive, that is, the Holy Church, in which Christians should be gathered and dwell in unity of faith and mutual love.”

The attribute of the bee that the Church was otherwise particularly keen to promote was that it does without the pleasures of the body. The Franciscan monk Bartholomeus Anglicus wrote in the thirteenth century that bees “are not medlied with service of Venus, nother resolved with lechery, nother bruised with sorrow of birth of children”.

The Renaissance would give new life to the image of the bee colony as a perfect monarchy, with a noble king that had been created by the writers of Antiquity. Erasmus of Rotterdam (1467–1536) had Seneca in mind when he wrote that the lord of the bees is the most powerful of all rulers because he refuses to oppress his subjects and is their benefactor instead. The bees love him and work for him with joy.

Shakespeare described the similarities between the bee colony and human society in Henry V, Act I, Scene 2:

… for so work the honey-bees,

Creatures that by a rule in nature teach

The act of order to a peopled kingdom.

They have a king and officers of sorts;

Where some, like magistrates, correct at home,

Others, like merchants, venture trade abroad,

Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings,

Make boot upon the summer’s velvet buds,

Which pillage they with merry march bring home

To the tent-royal of their emperor.

Detail from The Coronation of Napoleon by Jacques-Louis David, 1805–07. Musée du Louvre/Wikimedia Commons

Towards the end of the Renaissance the Aristotelian notion that bees were ruled by a king would be challenged, however. First of all by the Spaniard Luis Mendez de Torres who, in 1586, maintained that he had seen la maestra laying eggs with his own eyes, which meant she could not be male. In 1609 bee music The Feminine Monarchie was published by the English priest and scientist Charles Butler in which he wrote that bees had a queen, without, however, providing any evidence for this assertion. But as England had been successfully ruled by Elizabeth I for forty-five years it was not considered improbable that the bees too might have a queen. Butler’s book attracted a great deal of attention and is still considered to be a milestone in the literature on bees. Much later the Swede Marten Triewald would write that he had heard of a book by “an Englishman called Carl Butter” in which he argues that the bees have a queen although “it has become so rare that I have been unable to hunt it down either here or in England.” But even without reading “Butter”, Triewald was convinced that the queen was female. “Anyone who opens the abdomen of a queen with a flat-edged sewing needle or the thin point of a penknife when she is laying eggs will be able to see the ovaries and eggs for themselves.”

The first person to study the anatomy of bees using a microscope, and who thus eliminated – or should have eliminated – any doubt about their different genders, was Jan Swammerdam. But despite an increasing body of scientific evidence that proved the “bee king” was not a king, the question remained a sensitive subject throughout the eighteenth century. Human society was steeped in Christian belief, and the bee colony was a divinely ordained model of excellence. What kind of ruler and regime was the right one? Theology and monarchy were ranged against science and the Enlightenment. The debate and discussion of these issues were particularly fervent. In Spectacle de la Nature by Noël-Antoine Pluche, an early popular science bestseller from 1732, a count asks a priest who knows about bees whether it is true that bees have a queen. He receives a long and complicated answer – on the one hand, on the other – that concludes with a counter-question: What does the count think? It would have to be a queen, he says, because he has seen eggs in her abdomen. Although, he adds, he has no desire to get mixed up in a disagreement about this with someone who holds a different view.

Samuel Linnaeus described how the queen “accompanied by one or two bees, first sticks her head into a pipe (a cell) once her escort has poked at her rear: when she pulls out her head she immediately inserts her abdomen inside which reaches the bottom of the cell and then presumably has laid an egg, while her rear or abdomen remains inserted her escort has been stroking her head as though they were feeding the Queen or caressing her.”

When the republic was introduced and both noblemen and priests would be guillotined en masse, the beehive became a symbol of diligence and civic spirit.”

And yet despite this observation he hesitates over the sex of the ruler, writing now he, now she. He finds it inconceivable that “a single female can lay 400 to 500 eggs every day from Lady Day to All Saints… when she has so much else to manage besides.” Even stranger is the fact that the queen knows the nature of the egg before it has been laid as he/she lays drone eggs in drone cells, worker eggs in worker cells and queens in queen cells.

Eventually it was no longer possible to question that bee colonies were ruled by a female. But those who found this difficult to swallow might nevertheless devalue her status and appearance. “An awkward creature,” wrote the Englishman John Keys, “Not unlike a too tall woman in a dress that is much too short.”

In the course of the French Revolution, a new set of ideas as to what the beehive represented would come to the fore. It stood first for the collaboration between the nobility, the priesthood and the Third Estate in the National Assembly. But when the republic was introduced and both noblemen and priests would be guillotined en masse, it became a symbol of diligence and civic spirit. The problem, however, was that a single bee appeared to have power over all the others. The fact that it was a female did not make the situation any more palatable. She was the perfect match for the much-loathed Marie-Antoinette. The status of the bee sovereign – if there was such a thing – had to be determined, and this would be resolved by a debate that took place in 1794 (the year III, according to the Revolutionary calendar) at the new teacher training college, the Ecole normale. It was conducted between a student, Laperruque, and Jean-Marie Daubenton, a seventy-nine-year-old professor and well-known scientist. Previously a member of the Royal French Academy of Sciences and Superintendent of Le jardin du roi, the professor had skilfully trimmed his sails to the winds of revolution and would be rewarded with high positions under the new regime as well.

When Napoleon crowned himself Emperor and his wife Joséphine Empress, their red velvet mantles were strewn with bees embroidered in gold thread.

The best known of all bee allegories in history is The Fable of the Bees by the Anglo-Dutch philosopher and doctor Bernard Mandeville, a satirical account in elegant rhyming verse accompanied by an explanatory prose text. The newspapers and periodicals of the day were filled with furious attacks on Mandeville’s book. Entire volumes were written about how reprehensible it was. A court in Middlesex declared it a public nuisance. Priests thundered against the impious Mandeville from their pulpits.

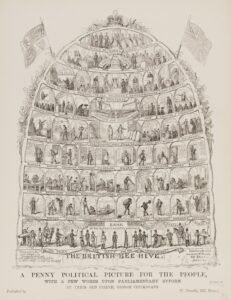

The British Bee Hive by George Cruikshank, 1840 (published 1867). V&A Collections

Today Mandeville is considered to be a prominent social philosopher and has been praised by posterity – or parts of it, at least. He has influenced economic theorists such as Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes as well as neo-Liberals and libertarians such as Friedrich von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises and Milton Friedman.

With the rise of the labour and non-conformist movements in the nineteenth century, the issue of who actually ruled the hive would be set aside. Instead, the straw hive came to stand for solidarity, hard work and altruism. The trades union movement in England published the periodical the Bee-Hive; in France there was La Ruche populaire. In the 1840s, when the Mormons settled in the area that would become the state of Utah, they called it “the Deseret State”. Deseret is the honeybee in the Book of Mormon. Utah would then become “the Beehive State”, with a beehive as its official emblem. In 1872 the first issue of Bikupan (The Beehive), a Sunday school magazine, was published by the Mission Covenant Church of Sweden.

The conservative cartoonist George Cruikshank responded to the labour movement’s claiming of the beehive as their symbol with an image of Great Britain borne up by the armed forces and the banking system, with Queen Victoria at the very top. In this hierarchy everyone knew their place and was happy with it.

This is an edited extract from from Bees and Their Keepers (MacLehose Press, £20)

Lotte Möller is a Swedish writer and journalist, and author of a number of classics in cultural and garden literature including a monograph on the lemon, which was shortlisted for the August Prize for Best Non-Fiction. She has also been a beekeeper. Bees and Their Keepers is published in hardback and eBook by MacLehose Press, translated by Frank Perry.

Lotte Möller is a Swedish writer and journalist, and author of a number of classics in cultural and garden literature including a monograph on the lemon, which was shortlisted for the August Prize for Best Non-Fiction. She has also been a beekeeper. Bees and Their Keepers is published in hardback and eBook by MacLehose Press, translated by Frank Perry.

Read more

@maclehosepress

Author portrait © Nille Leander

Frank Perry has translated many of Sweden’s leading contemporary writers, poets, and playwrights, including Stig Larsson, Henning Mankell and Katarina Frostenson. His translations have won the Swedish Academy Prize for the introduction to Swedish literature abroad, the prize

of the Writers’ Guild of Sweden for drama translation, and his 2016 translation of Lina Wolff’s Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs (And Other Stories) was awarded the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize and the Society of Authors’ Bernard Shaw Prize.