Recapturing infinity in the present

by Mika Provata-Carlone“Am I the same person?” asks Fela Rosenbloom, whose narrative of her early life in Łódź, and her internment in no fewer than six German labour and concentration camps, prefaces her husband’s longer, very different account of the 20th century. Miracles Do Happen is a joint memoir of war, Jewish life, community and identity, survival and reintegration into an unreliably bright new world determined to reclaim normality. Elemental though it may seem, Fela Rosenbloom’s question is the fundamental ontological and historical aporia for everyone in the wake of the Holocaust – and of any atrocity, private or ecumenical. Fela and Felix Rosenbloom each propose a very different, particular answer, offering at the same time a tactile and forthright itinerary of a way beyond devastation, which is resolutely contingent upon a relationship of absolute frankness with memory – and with one’s duty to humanity.

It is this principle of frankness, and the transcendental as well as humanising value given to storytelling, to the power of stories to resurrect, save, rebuild lives, that endow Miracles Do Happen with a special kind of evocativeness, and give it the authority to lay claim on our emotions, our intellect and our conscience. Both segments of what is not simply individual or conjugal, but essentially collective memory, are striking for their unmediated, un-literary voice, which proposes, instead of stylistic virtuosity, the quality of a distinct human sound and presence, a verbal timbre certain of its purpose, its ethics of narrative, and especially of the legitimacy of its communicative potential. The Rosenblooms are in no doubt that there can be, if not poetry, then at least poesis of words after Auschwitz: in fact, they proclaim that such words are what our lives depend on.

Both have the gift of turning strings of words into tales that conjure up worlds and lives now out of reach – lamentably, often beyond our society’s interest to understand, be unsettled by or to sympathise with. Fictionalising a life becomes a signal of public awakening and an act of refashioning in their case, a means towards the reconstruction of what was lost and must be recovered through remembrance, and especially through the genuineness of a human gesture of connectedness.

The two narratives are complementary, as were their lives and human dispositions; they are equally and sharply contrasting, even antithetical, as were also their experiences, their world outlooks and legacy.”

Miracles Do Happen was written as a private record to be shared in the intimacy of a family audience; it was intended to be a personal narrative securing the edges of a fraying communal fabric. Yet its voice was deemed to have a resonance that exceeded closed spaces, a select readership or individual ears – it was decided that the story it contained had not been told in this manner, or in this permutation, and that it needed vitally to be made public, in order to be heard, or even to be heeded. Publishing it was undeniably the right decision; that it was possible for the book to be published by the family firm, when printing and typesetting, book-making and the dissemination of words, ideas, history and stories is so very central to the individual journeys of its authors, makes for a very unique volume to hold in one’s hands.

The two narratives, Fela’s and Felix’s, are complementary, as were their lives and human dispositions; they are equally and sharply contrasting, even antithetical, as were also their experiences, their world outlooks, the ethno-genetic inheritance and legacy they each came with. Fela’s account is a very personal journey down paths of memory which, because of their value of individual quotient, acquire the significance of a universal code of being and survival, similar to Bella Chagall’s diaries, yet lacking the latter’s potential for humour, hyperbole, oneiric fancy. Fela came from a similarly orthodox, close-knit background, and hers is a very sensitive portrait of an older, more ritualistic way of life, as it converges with a newer, more instinctual yearning. Fala’s portrait of Poland is not flattering, yet it is particularly revealing, perhaps even more so today. Like Alfred Döblin’s Journey to Poland (1926), she offers us a relief portrait of her city from every facet: the bustle and enterprise of her community, its codes, rhythms and dreams, and the anti-Semitism and social discomfort she feels surrounded by. “I am Jewish and I was born in Poland… Outside our quarter Jews were often physically attacked. I was always terrified of the hatred shown towards us.” Even with the distance of several decades and the perspective afforded by different countries, Fela’s prism retains its sense of fragmentariness, the distortion imposed by exclusion, the aggression on any perception of self-image or ethnic identity. We get a sense of someone trying to refocus a sharp but unwieldy lens in order to afford clarity, explanation, understanding, closure, or perhaps even guilt or penance, to a blur of horror that demands a duty of confrontation and assessment.

Fela’s tone is clipped, precise, as though carefully restoring each memory, each detail of an obliterated life to its rightful (no longer possible) place. It is a struggle to make words speak the unspeakable. Her style is simple, lento, reluctant, and at the same time defiant, determined, full of resurrected emotions, while remaining untainted by sentimentality or kitsch fictionalisation. Her people (they are not characters) are infallibly genuine, palpably real, requiring no embellishment or beguiling falsification. And yet, neither are they one-dimensional, merely biographical, gossipily naturalistic. The experience of history, the trauma of the Holocaust, the challenge and duty of a particular heritage, endow each with the aura of a persona: they have acted and been acted upon in a total, ultimate drama that should never be forgotten or repeated.

Fela gives us raw, immediate experience without retrospective analysis, except to offer details which underscore the sense of apocalypse without revelation, and the surreality that made an impossible future possible.”

Fela went through the labour camps of Unterdiessen, Buchloe and Augsburg in her attempt to survive the ghetto of Łódź, before being sent to Auschwitz, which she miraculously survives. She is then pushed on to Ravensbrück, from where she escapes as the war comes to an end. She gives us raw, immediate experience without retrospective analysis, except to offer details which underscore the sense of apocalypse without revelation, and the surreality that made an impossible future possible. Word by word, step by step, we see the ‘natural course’ that led from communal history and existence to persecution, to the retrieval of being in the world. The phatic quality of this sequence, the ostensible lack of problematics, accentuate the inherent social evil, the sinister irony that made the Holocaust possible. Fela’s is an emotional narrative and existential journey. It is also a female narrative through and through, both in what it says and in the silences that it inevitably succumbs to.

Felix’s story is that of the non-concentration camp survivor. Even the experience of Soviet labour camps, the visceral confrontation with that ideological, social and material reality, stands in stark contrast to everything Fela had to endure as a state of being. Felix’s narrative could join Benjamin’s or Koestner’s memoirs of their childhood and young adulthood as a log of urban life, evolution, history and social analysis. His account is richer, more detailed, historically discursive but also mischievous and ribald. Not everything he says or does is strictly kosher. He interweaves socio-historic commentary with personal biography in a way that resurrects an entire era as well as individual voices of personal significance. Of particular interest is his probing into the awakening of a new Jewish conscience, a more consequential and proactive Jewish agency. He traces the genealogy of causes and effects since the Russian Revolution of 1905 to the time the memoir was written, thus creating a singular thread of the symptoms of the times. His is a historical, social and cultural documentary with a human voice.

There is a sense that he must speak for a whole generation and nation, and he does so with staggeringly objective humanity. The most resonantly devastating are the unconfirmed facts: a friend who “perished in a camp somewhere” evokes the fate of the undocumented many, those who were yanked from homes, arrested at random at roadblocks or during systematic raids, to be shot or loaded onto railway cattle trucks or to the sides and fronts of trains as human shields, and who did not even have the chance to have their deaths recorded. In the telling of a personal odyssey, Felix provides an unflinching view into the “very fertile ground” Nazi anti-Semitism found in Poland, the inertia of England and France during the 27 days that it took for Hitler to occupy the country, the systematic, instant application of racial laws against Jews. He offers rare insight into Russia during the time of the Pact of non-aggression with Hitler’s Germany, into Soviet anti-Semitic practices, bureaucracy, and the delusions of a dogma that had seemed like an ideology. German death camps stand side by side with Soviet labour camps in what is a J’accuse of anger and incomprehension.

Felix’s account is richer, more detailed, historically discursive but also mischievous and ribald. Not everything he says or does is strictly kosher.”

Felix’s recording of every detail recovers something that is lacking in most survival narratives which stop with the end of the war, the liberation from the camps, or the return to a home, however devastated. Here we are asked to experience the path of recovery, of re-humanisation, of faith and of practical, material effort. The density and efficacy, the spontaneous responsiveness of the Jewish network at home and abroad is quite startling, given the context of the times, the dogmatics of each country, the experience they have emerged from. There are vignettes of everyday life but also surreal images: in 1946 Fela and Felix have left Poland for a DP camp in Germany. They decide to join “a kibbutz that occupied a farm near [Munich]. We worked in the fields during the day, and in the evenings we had a lot of fun, learning Hebrew songs and dances.” Dachau too is near Munich…

A particular attraction of Felix’s narrative is his account of the perambulations and tribulations of Jewish politics during that time, especially the evolution and devolution of the Bundists. He offers shrewd political commentary, deductive analysis of Soviet ideology, its promises, means and illusions, but also of the dynamics and polemics inherent within the global Jewish community. Because unfiltered, unscholarly, Felix’s perspective is an especially interesting one.

Episodes or certain moments in time loom larger than others – not disproportionally, but magnified to suit human measurements of history and experience. At their core lies the need, true for the wider generation that came out of the war irrespective of culture, nation or religion, to retrieve and to voice a certain sense of pride, to lay a determined claim to a dignity that had been violated and taken away. It is this plasticity of perception, significance, broader horizon, that renders Felix’s account, in particular, so vivid and yet so concretely objective at the same time.

Felix and Fela left Poland for France, which they left in turn, at the start of the Korean War, for Australia. Their story chronicles the passage from an old to a new world, from death to life. It is also a farewell to Europe, in many ways, and to its troubled record of history that cannot be erased. Australia was the blankest page they could find, unblemished, we are told, by a war on its soil. On that blank page, Felix and Fela traced a rather remarkable life, which resonates with so much of the human qualities our society now thirsts for. Miracles Do Happen is a harrowing yet infinitely reassuring read. It is a reminder and a promise, as well as a testament to the value of a purer, simpler diction.

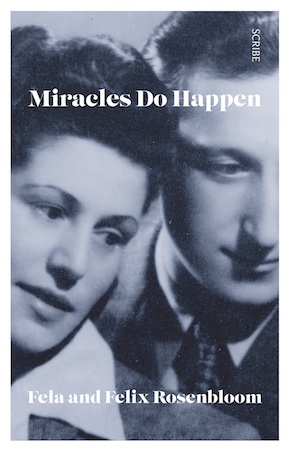

Fela Perelman and Felix Rosenbloom were born in Poland in the early 1920s. They grew up in the same street in Łódź and became sweethearts, before their lives were devastated by the Holocaust. After the war, they reunited, married, and moved to Paris. They migrated to Australia with their son Henry in 1952 and settled in Melbourne, where their second son John was born. Felix died in 1995 and Fela in 2018. Miracles Do Happen is published in paperback and eBook by Scribe, which was founded by Henry Rosenbloom in 1976.

Read more

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

Monday 9 April

Monday 9 April

Book launch: Miracles Do Happen

6:30 to 8pm

Free

Reading, remembering, resisting: publisher Henry Rosenbloom launches his parents’ memoir at The Wiener Library, London.

More info