Riad Sattouf: Tykes and tyrants

by Mark Reynolds

“Brilliant, sharp and surprising.” La Repubblica

In The Arab of the Future, his first book to be published in English, bestselling French comics artist and former Charlie Hebdo contributor Riad Sattouf begins an epic five-volume graphic memoir about his formative years as the son of a volatile but vulnerable Syrian father and a forbearing French mother. Told with childlike wonder and the merest hint of mature understanding, it’s a wide-eyed and unforgettable tour of the early days of Muammar Gaddafi’s Libya and Hafez al-Assad’s Syria (via rural Brittany), as Sattouf’s professor father pursues an unbridled ambition to help build a proud Arab nation through the power of education.

MR: What triggered your decision to create a graphic memoir of your childhood? Was it a sudden inspiration, or a long and deeply held desire?

RS: I had this project in mind for a very long time, but I was thinking of a good way to tell the story. I’ve been making comics for fifteen years now, and I didn’t want to start by telling my story because I didn’t want to immediately become The Arab of the Comics World. So I started to make other comics and I directed two movies, not from my life story, but from creation and observation. Then in 2011 I tried to help a part of my family that was still living in Homs come to France, and I had a lot of difficulties obtaining authorisation. It got me thinking I have to make a comic about this. But if I wanted to tell this story, I had to tell it from the beginning.

The title is monumental, setting up the hyperbolic vision of pan-Arabism, but at the same time it’s a wonderfully inappropriate description of you as this disoriented mixed-race kid at the centre of the story. Where did it come from?

It’s a phrase my father used. Like all children I didn’t want to go to school and my father was from a poor family. He was the only one who went to school, who was able to learn to read and write. He loved school and education because it gave him status. So when I didn’t want to go to school my father was always telling me, “You have to go to school because the Arab of the future will go to school.” In his time the Arab world was uneducated – or miseducated – and for him education should be for everyone. I also like this title because it’s outdated, it’s a form of nationalism from another age.

When you are young you believe that everything that comes out of the mouths of your parents is the truth.”

The book is described as depicting a childhood lived in the shadow of three dictators – Gaddafi, Assad and your father. Was your dad as bad as all that?

How can I answer this? I wanted to tell the story from the point of view of a boy who admires his father. Children tend to be forgiven for everything. When I was young something that intrigued me is that when a child commits a crime, the parents could face jail. Children are almost holy: they can say anything, do anything, with no sense of morality. I also wanted to show the point of view of my father, who was for modernity and education, but against democracy. He was an extremist, he wanted to make a coup, he wanted to execute people, he was for the death penalty. It’s a strong paradox.

And his views get stronger and stronger as the book goes on…

Wait till you see the rest of the story! I wanted to show how, when you’re growing up, it takes a long time for a child to understand what his father is really saying, because when you are young you believe that everything that comes out of the mouths of your parents is the truth.

Your father is shown to be flamboyant and bullish, but also prone to humiliation.

I tried to be honest in describing my family at that time. I waited a long time to tell this story because I don’t often like autobiographical stories. When I read stories of people telling their life, especially in comic books, sometimes they are too gentle with themselves and their family. They say their father or mother is so fantastic, you can feel that they’re not telling the truth. Everybody loves their parents, and they refuse to see them as normal people. I have a strong interest in showing the weaknesses of my characters.

The kids in Libya and Syria could be quite brutal.

I promise you, they were not. It would be unfair to say that because they were just more mature than I was, than French children. In Syria at five years old they were able to walk alone in the village, and to go and have adventures. French children at five, as I describe in the book, were big babies. I was like that, I was a big baby. It was a peasant life, like in Dickens, where children are left on their own and steal in order to eat. This is the difference. Children in Europe, in France, are overprotected. At 20 years old, they’re still babies.

The book opens when you are two years old. What are your earliest memories of being uprooted from France to Libya?

Actually I have a very precise memory of my early childhood. I have a better memory of my early childhood than from last week. It’s like another world in my head where I can go back and I see things. I have memories from before what I’m telling in the book – situations and smells and tastes and sounds and visual memory. I recreated all the dialogue in the book, but each scene comes from a real memory. For example at the beginning there is a scene where my father is reading Gaddafi’s Green Book and my mother is laughing at what he’s reading. Of course I recreated the scene. I took real sentences from the book but in reality I don’t remember what my father was saying, I just remember he was reading the Green Book and my mother was laughing at what he was reading. It’s from a true memory.

I was convinced as a child I had a destiny to become a comic artist, and it’s very funny to show how a misunderstanding could decide a whole life.”

You experienced smothering adulation as well as name-calling and bullying. Which was worse?

Oh, I preferred to be admired!

But what’s the long-term effect of that?

Like I was saying, I have very precise memories of that time, and I remember a world where everybody was smiling at me. All day you’re the most precious thing, and you think you’re so wonderful. But then comes a time when your body changes and you become a teenager, and this is over. But somewhere in your head you still think the world is still looking at you and you don’t understand why it’s not happening any more.

One bit of praise that clearly did have a positive effect is when your drawing was admired.

Yes, I wanted to express in the book that a lot of the characters think they have a destiny, and for myself I was convinced as a child I had a destiny to become a cartoonist and comic artist, and it’s very funny to show how, in fact, it could be so futile an event as a misunderstanding that could decide a whole life. As I tell in the book, one day I made a drawing and my grandmother thought it looked like President Pompidou, so she showed it to my father, who was really impressed and said, “Oh my God, it is Pompidou!” They asked me “What did you draw?” and I said “Oh, it’s Pompidou,” and so I was a genius! But I liked the look in their eyes, so I decided to draw and draw to find in their eyes the same admiration, and it’s what I’m still doing today.

Did you ever tire of drawing Gaddafi and Assad for this book?

No, no, no, I like drawing men of power.

Although you don’t see yourself as a political cartoonist.

I think each book, each work is political, but here I’m telling stories that happened to me. It only became political because of the time and the context, but I don’t wake up in the morning and say, “OK, I’m going to make a humanist, leftist story now, to impress everybody.”

You were enthralled by Tintin at an early age, and have said that as soon as you realised that the books were drawn by a human, you wanted to become a comics artist. What age were you then?

I think I was five or six.

And when were your first drawings published?

My first comics came out when I was 19. Each week I’d send drawings to all the publishers and they’d reply, “No, no, sorry, no, thank you but no.” I was thinking it was impossible to have 100 per cent rejection, so I’ll send 100 projects and there will be one, or at least half of one that someone likes.

Which was the first publication you appeared in?

Oh, it was not very famous. I was only the drawer and a scriptwriter wrote the words. My first personal comics, where I wrote and drew by myself, were published when I was 23.

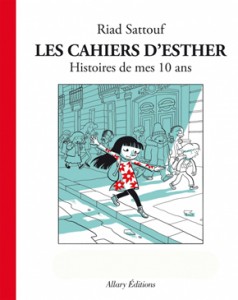

Your long-running strip for Charlie Hebdo, La vie secrète des jeunes, was based on overheard conversations among young people on the streets of Paris, and now Les cahiers d’Esther in L’Obs is based on stories told to you by a girl who was 9 years old when the strip started and is now 11. The first ran for ten years. How long do you expect the Esther strip to continue?

I would like to tell the story of this young girl until she is 18. She’s an ordinary middle-class little girl who tells me stories about what she likes in life, what she thinks about justice, death, love and everything, and it’s interesting to observe what comes into her mind, and how she will develop as an adult. In The Arab of the Future I’m describing my youth in the 80s in the Middle East, and at the same time I’m describing her youth today in France, in a more privileged place.

Will her true identity ever be revealed?

No, never.

Even if she decides to stop telling you stories?

Maybe one day she’ll say “I don’t want to do this,” or “It’s me,” but I don’t think so.

I wanted to talk about your films as well. How did your first film, the teen comedy Les Beaux Gosses [The French Kissers] come about? I understand the producer approached you.

I’d published several books on teenagers, with themes of teenhood, and the producer Anne-Dominique Toussaint liked my comic books and proposed that I write a script based on one of them. So there I was in the office of a producer, and I thought, “OK, it’s your day, say any old rubbish!” So I told her I wanted to write an original script, and I wanted to direct the movie. And she said, “Yeah, why not?” So that’s how it began.

And it got fantastic reviews and audiences [also winning a César for Best First Film]. Then your second film, Jacky au royaume des filles, was a satire on gender reversal.

But it had absolutely no success! I tried to invert gender codes to the maximum, so I created a parallel world where women had power and men had to stay at home and raise children, and women had the right to have a lot of husbands. And like in our world where men are obsessed with the bodies of women, in this parallel world women are obsessed with men’s bodies, and force them to cover up. It was a huge failure, no one was interested, so I went back to making comics. I realised that comics are my real passion, my obsession.

Finally, I can’t help but ask if you think the attacks last year on Charlie Hebdo and the Bataclan say anything about intolerance or prejudice that is particular to France? I happened to be in Paris within days of both attacks, and was struck by a city-wide feeling of solidarity and sympathy, and a determination to carry on as normal.

I’m very bad at analysing big political events, and hesitate to give an opinion. Those attacks of course were a huge trauma, but I think perhaps France is a stronger country. Sometimes people ask me, what do you say to people who say France is a racist country? I’ve travelled to a lot of places on earth, and I haven’t yet found a country that is less racist than France. In Syria, for example, in my village everybody was incredibly racist. And when I went to Japan I found it a very divided society, they make a strong separation between gaijin and Japanese. In France it’s not like that. The French like to say bad things about their country – Oh my God, we are destroying ourselves, it’s over! – and it never happens because people are intelligent and they want to live together. I’m quite optimistic. I don’t know, maybe I’m a fool.

I guess the Front National have been around for decades, and they’ve still not seized power.

But each election people say, “Aargh, they’re coming! The Nazis of the Front National are coming!” – and they never win. It’s always the same. That’s why I like France. Although its people are always debating, I like this type of society. Of course there are racist people and a lot of injustice, but people are trying to live together. For me racism in society is when you have laws that are racist, and in France there are no racist laws. In some countries your ID card has to state your religion. But I can’t think of a single country where racism is very lower than in France. Racism is the dark side of humanity.

Even where a society seems to make the right choices, and has all the well-meaning laws in place, you find extremists. In the Scandinavian countries, for example.

Yes, of course. And there are Italians from the north and south that hate each other, and in Ivory Coast or Mali, for example, you have ethnic groups living side by side who hate each other. In Syria, people in my village hated people in the next village just two kilometres away. I think it’s always a human story to hate other people before learning to know them.

And tolerance will only come about through understanding.

This is a positive message. I’m optimistic. I’m sure in 300 years everything will be cool.

Riad Sattouf is a bestselling cartoonist and filmmaker who grew up in Syria and Libya, and now lives in Paris. The author of four comics series and weekly columns in the satirical publication Charlie Hebdo and L’Obs, Sattouf also directed the films The French Kissers and Jacky in the Women’s Kingdom. The Arab of the Future is his first work to appear in English and is out now in paperback from Two Roads. Read more.

Riad Sattouf is a bestselling cartoonist and filmmaker who grew up in Syria and Libya, and now lives in Paris. The author of four comics series and weekly columns in the satirical publication Charlie Hebdo and L’Obs, Sattouf also directed the films The French Kissers and Jacky in the Women’s Kingdom. The Arab of the Future is his first work to appear in English and is out now in paperback from Two Roads. Read more.

riadsattouf.com

@RiadSattouf

Author portrait © Olivier Marty

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.