Riddled words, puzzled lives

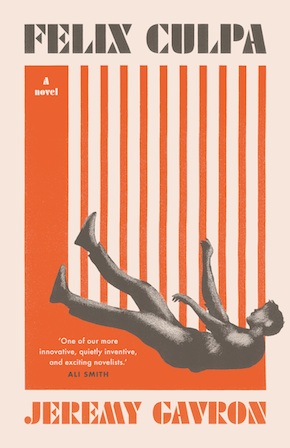

by Mika Provata-CarloneThere is something deliciously provocative about a work of literary fiction that begins with the statement “If it sounds like writing, rewrite it”. It is a pronouncement that holds the reader in irresistible tension: will this prove to be the most flawless of narratives or be exposed instead as the most bombastic of bathetic ironies? We read on, to experience triumph or thundering fall.

In Felix Culpa, there is no doubt that Jeremy Gavron utilises this tension, this temptation, to engage and to entice; to challenge and lure; to flex not only his own muscles as a writer, but also our own consciousness and consciences as readers. His ploy is not a novel one by any means: to create, as though by linguistic and mythopoetic alchemy, a new story out of the borrowed elements of tales that have already been told. To weave together echoes, allusions, textures, cultures and lives into an original piece of fiction that has only just been born before the reader’s eyes. Horace and Virgil did it before him, as did Ovid, even more flamboyantly; the modernists, to make one grand literary leap, made such ‘referencing’ their bread and butter, from Pound to Joyce, to the Vorticists, or to the later Beat Generation and the self-assured postmodernists.

What may be called Gavron’s particular achievement is that he brings back a by now almost standard modernist technique to launch new literary ventures and express what might seem like the terminus of our existential anxieties. The story can be described as predictable: a writer drained of inspiration and perhaps even talent, seeks revelation in the darkness of a prison where he is the writer in residence. There is a classic film-noir subplot of grittiness, defeatism, bleak introspection and dogged perseverance. Of foil characters who are larger than life and blurred enough to feel like wraiths in a world of eternal ghosts. There is an unsolved crime, flashes of an existence gone to waste, a deeply human story that has not been told. The writer’s quest will be for the words to say it, for the clues that will lead to a plot, to coherence, to a regained faith in language, narratives, life stories – ultimately in life itself.

Gavron is essentially a Mary Shelley of words: he seeks to galvanise old sentences, the members of all stories, with new life, in a new body made of the severed parts of many others.”

Gavron’s set task, to craft his novel by means of selected shreds and tatters from the writings of others, is near-Herculean: “the great majority of the lines in this novel are sourced word for word from the hundred or so books, by some eighty authors” listed in an appendix to the novel. “Fourteen of the chapters, including the last nine [of a symbolic 33] are made up entirely of sourced lines.” His challenge is to produce a seamless mosaic, where the tesserae do not distract from the vision of the whole, while retaining their full value of individual resonance, the scintillating secrets of the image they once belonged to. Gavron is essentially a Mary Shelley of words: he seeks to galvanise old sentences, the members of all stories, with new life, in a new body made of the severed parts of many others.

More than an experiment, Gavron’s novel (or perhaps novella) might best be described as an extreme exercise in the ethics of writing and of language. As the narrator searches for sentences, words and stories that belong to others, and which will awaken in him the need to tell the untold story of a fragment, or offer him the total narrative of fragments that vicariously will fall into place, what is in question is originality itself, thought itself, the existence (or not) of an individual consciousness. To what extent do we own what we say, or even the words to say it?

Felix Culpa is on the one hand a daring piece of writing (and sleuths of the “sourced lines” will undoubtedly have a field day, creating blogs or search engines to track them and to capture them, like big game trophy hunters). On the other hand, it is a harrowing philosophical and existential undertaking. Gavron has written before the untold story, he has a strong fascination with howling absence. He has sought before the explanations for lingering questions – especially the questions relating to guilt and abandonment, to destruction and creation. With Felix Culpa, what was autobiographical before now becomes more ecumenical – a testament to our state of language, our state of being, and of relating. The sourced fragments, the amputated parts that will be reunited to form a new species and a new whole, never lose their sense of being stumps, spolia, barbarically or judiciously collected remnants of destruction. The resulting haziness and inchoateness of language, the exposure of its limits, the tacit or explicit challenge against cultural or systematic conventions that make words the signifiers of lives and a vehicle of meaning, raise the question of what value we can assign to language today. A poet once said that “a literary movement is a movement of the soul” – and perhaps this is true in a wider sense: the quality and timbre of our writing reflects the mettle of our society’s psyche, it is a barometer of the state of our humanity.

From such a perspective, Felix Culpa comes with the heavy semantic panoply of its title: another “sourced line” from the Catholic mass for Easter. The fall from Paradise is seen as the happy misfortune that led to the advent of the Saviour. St Augustine would push this even further: the Fall is an illumination of the divine plan, “For God judged it better to bring good out of evil than not to permit any evil to exist.” The Christological echoes and nuances in Gavron are many and unmistakable (including the use of 33 chapters, as many as Christ’s mortal years), as is the subtext that our times are post-redemptive, perhaps even beyond salvation. Sourced lines become lifelines or Ariadne’s threads: they lead to the heart of the labyrinth of our humanity, and perhaps back out into the light again.

Given the systemic nature of language, can it (and therefore also what we create with language as imagination and utterance) be truly original?”

Gavron’s novel is taxing on the reader’s mind. Both for the proximity to tragedy, devastation, abjection and despair that it imposes, but also as a result of the relentless questioning of the very possibility of language and meaning to exist that it postulates. As we read each severed yet seamlessly chained-up line, the compulsion to hold on to an individual voice, to a semantic value, to a narrative truth or at least flow, often becomes overwhelming. How much, Gavron seems to be saying, of our discourse is original rather than expertly rearranged prior patterns? How much of our human enunciation has true value rather than being the programmatic consequence of structures inherent in the linguistic system? Given the systemic nature of language, can it (and therefore also what we create with language as imagination and utterance) be truly original? Gavron pushes these questions to the most extreme limit – and ultimately it will be up to the reader to assess their validity and the success of his project.

As we are invaded by the echoes of the books from where the lines have been sourced, there is a disturbing feeling of voyeuristic intimacy, of a vicariousness of meaning and lives that makes relationships, real and intellectual, abortive. Felix Culpa is perhaps about trying to make sense out of the chaos of echoes each of us leaves behind. In this manner, the “sourced” stream of consciousness of a writer’s journey becomes a relentless diatribe against the decomposition and fragmentation of our humanity, our society, our history and individuality. It is even an exposure of the tolerated anomalies that have led to the rise of anarchist or alt-right ideologies which now dominate as mainstream, natural alternatives. The echoes of T.E. White’s ant language, Faulkner’s cold anger, blurred ugliness and the sense of a stained, soiled, irreparable society, Papadiamantis’ razor-sharp psychological analyses of the worldly and the holy, are strong in Gavron’s text as well, as is the keyhole or dirty window perspective of a scorched earth. Felix Culpa is a narrative journey of self-destruction as much as it is a journey through destruction.

Does Gavron succeed in the end? In many ways he does, and quite spectacularly. Each of those disjecta is aligned to the others by an almost transcendental process of signification. We do get one distinct individual story out of the clashing junction of so many. Yet even when we find ourselves gripped by this fogged-up humanity looking for light in order to look at itself, there is an unremitting sense of cumbersome cleverness, virtuosity and of too-muchness. The emotional intelligence behind Felix Culpa however certainly makes it a rewarding encounter, and a promise yet to be fulfilled. The last line is that the “End is not yet told”, so here’s to the next glimpse of mortality and of eternity from Jeremy Gavron.

Jeremy Gavron is the author of six books, including the novels The Book of Israel, winner of the Encore Award, and An Acre of Barren Ground; and A Woman on the Edge of Time, a memoir about his mother’s suicide. Educated at Cambridge and New York universities, he started out as a journalist and was a correspondent in Africa and Asia. He has been writer-in-residence in a prison, a hospice, and at University College, London. Based in London, he also teaches on the MFA at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina. Felix Culpa is published by Scribe.

Jeremy Gavron is the author of six books, including the novels The Book of Israel, winner of the Encore Award, and An Acre of Barren Ground; and A Woman on the Edge of Time, a memoir about his mother’s suicide. Educated at Cambridge and New York universities, he started out as a journalist and was a correspondent in Africa and Asia. He has been writer-in-residence in a prison, a hospice, and at University College, London. Based in London, he also teaches on the MFA at Warren Wilson College in North Carolina. Felix Culpa is published by Scribe.

Read more

Author portrait © David Katznelson

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.