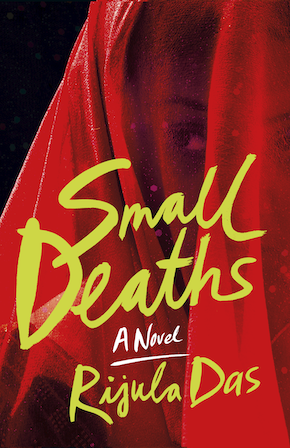

Rijula Das: The constant smallness of being

by Karin Salvalaggio

“Rijula Das is a writer to watch.” Avni Doshi

Set in Calcutta’s notorious red-light district Sonagachi, Rijula Das’s debut Small Deaths resists lazy stereotypes. Years of research have provided Das with an intimate understanding of the power dynamics at play between the madams, pimps and police, and how their often-cruel manoeuvrings have devastating consequences for the endless stream of girls and young women trafficked into modern-day sex slavery. If their families don’t betray them, a helpful stranger at a train station will. Yet this is not a book without hope, as there are signs of resilience everywhere in Sonagachi. The sex workers live full lives. They have children, build friendships, and sometimes marry. And for many, a locked room in brothel is the only security they’ve ever known.

Now in her late twenties, Lalee was sold into sex work by her family as a child. Her dreams of freedom are tinged with an innate understanding that “hope was a bad survival strategy in Sonagachi.” Beautiful and fiercely intelligent, she has long since internalised her shame: “She couldn’t look in the mirror, its spotless surface too exposing, too confronting for her to endure.” Her loyal client Tilu Shau is also ambitious. Low caste and impoverished, he ekes out a living penning erotic novels while aspiring to write stirring histories of his beloved Calcutta and one day free Lalee from the Blue Lotus, a sprawling brothel run with an iron fist by Shefali Madam.

Following the brutal murder of her friend Maya, Lalee is lured upstairs to work with high-end clients who are willing to pay more money. She soon finds herself in a dangerous world defined by corruption and sexual brutality on a scale she never imagined possible. She will need all her courage and strength to escape Maya’s fate.

Maya’s murder sets off weeks of protests outside the nearby police station and a candlelit march through the streets of Sonagachi. For the NGOs and cooperatives that long to offer the sex workers some semblance of protection and justice, “real crime was about waiting.” Police reports are filed but days and weeks pass by before the authorities bother to lift a finger. While the sex workers’ stories will break your heart, few women in Calcutta escape the daily grind of objectification and degradation: “At one time or another, every woman is turned into a profanity.”

Karin: The world depicted in Small Deaths is dangerous, disorientating and oftentimes chaotic. There are moments when it feels like historical fiction, but then someone whips out a smartphone and you’re reminded that the novel is set in the here and now. This is not long-lens fiction. Calcutta and Sonagachi are fully realised settings. What research did you have to do to achieve such a high level of authenticity? Where did you learn so much about Calcutta’s red-light district and the lives of the women who live and work there?

Rijula: Small Deaths is based on years of my doctoral research, which focused on sexual violence on women and its relationship with public space – how gendered bodies are allowed to use public space, how we demarcate and gender space, and the violent consequences of using this space. I was very interested in understanding the colonial origins of Sonagachi and how it shaped the modern red-light district. There is also plenty of case studies, documentaries, conversations and testimonials of women and intersex persons who live and work in Sonagachi. While the book needed a significant amount of research to do it justice, it also draws on my experience of living in Calcutta for years as a young woman.

The history of a place, its origins, have a lot of bearing on how a place is in the present. Sonagachi, like Calcutta itself, wouldn’t exist without imperial expansion.”

Calcutta transcends the role of setting and steps effortlessly into the realm of character. The city is vibrant, complex, corrupt and stratified, with one foot firmly rooted in its colonial past while the other is racing toward its future. Tilu Shau is fascinated by its rich history and dreams of the days when Park Street was still a jungle frequented by tigers and thieves. Such reveries are unusual to find in a crime novel. Why did you feel it was important to delve so deeply into the history of the city?

In many ways, Small Deaths is a novel about, and of, Calcutta. Sonagachi is a neighbourhood of North Calcutta, but I needed to see the brothels of Sonagachi in the context of the city at large. Like me, Tilu Shau is also fascinated with the rich colonial history of Calcutta and, unlike me, he dreams of becoming a historical novelist. I also think that the history of a place, its origins, have a lot of bearing on how a place is in the present. Sonagachi, like Calcutta itself, wouldn’t exist without imperial expansion, which made me interested in exploring this history.

Small Deaths is a dignified portrayal of a vibrant community of women. For many of the prostitutes, it’s the only safe place they’ve ever known – the only family they’ve ever had: “It was not a good life, not always, but sometimes it was, and despite everything else, it was theirs.” Lalee, Amina, Nimmi and Malini support each other. When Maya is murdered, they gather at the police station to demand justice or, at the very least, an official report. This is a point of view that is largely unrepresented in fiction. Would you concur with Australian author Sulari Gentill’s assertion that “Crime fiction is the new literature of resistance”?

Absolutely. One of the storylines in Small Deaths is about the ongoing and unfinished fight for sex workers’ rights. I wanted to give space to this grassroots movement by sex workers that has achieved an incredible amount in Sonagachi. Although I didn’t see Small Deaths as crime fiction, but rather as an exploration of the repercussions of the deaths that we let slip through the cracks. Gendered violence affects the individual but also the community around that individual life. This is where the title is resonant for me. I’d love the reader to be able to peek into the real political struggle and achievements of sex workers as labour rights activists, sexual health advocates, and people at the margins of society organising collectively to better their life and circumstances, rather than a romanticised version of sex work that we are used to seeing.

Now in her late twenties, Lalee was nine when she became one of Shefali Madam’s Blue Lotus ‘girls’. After Maya is murdered, Malini, a friend who runs the Sex Workers’ Collective, believes she can force the police to take action. Lalee “wanted to have Malini’s absolute faith, her recalcitrant rage and bullish optimism, but she had learned her lesson well – there was no hope, no escape.” Lalee will have to find something to believe in if she wants to survive the hell that is coming her way. What or who was the inspiration behind this incredibly compelling character? Will we be seeing more of Lalee in future novels?

Small Deaths is a standalone novel, so I doubt we’ll see Lalee again. But Lalee was a very difficult character for me to write. Her experiences are an amalgamation of many people’s stories and experiences in Sonagachi. Every other character felt completely familiar to me, but Lalee was the central absence around which I was writing. Every sentence I wrote for Lalee, I needed to pause and ask if it felt authentic, if it rang emotionally and ethically true. It wasn’t conscious, but in hindsight that was the right way to approach writing Lalee. It’s very gratifying to see readers connect with a complex, not always likeable, female character.

A culture heavily invested in the goddess/slut dichotomy, and where women have traditionally been associated with ideas of purity and treated as possessions, struggles with seeing women outside of their gendered roles.”

Tilu Shau is the keeper of Calcutta’s history and the author of a series of modestly successful erotic novels. He gives the reader a sense of time that has elapsed since Calcutta’s colonialist beginnings and a glimpse of the city beyond Sonagachi. He loves Lalee but she is unknowable, so he creates a fictional world where he adds a narrative to her life that fits his preconceptions. He is fully aware of his place in Indian society but longs to reach beyond those predetermined boundaries. That his writing “was allowed to exist in a world where he himself felt out of place. It was a miracle.” Tilu is a wonderful character. Could you please discuss how he came to be play such a large part in the narrative?

When I first started writing the novel in 2014, Tilu was the central character who led the way into the novel’s universe. It started with the first chapter where Tilu comes to visit Lalee. I think of Small Deaths as a novel about dreams, among other things. Tilu is possibly the best dreamer in the novel. His story is also weighted with his caste identity; he is low caste and comes from a historically marginalised community even if his family wasn’t poor. The insecurity he carries is also due in part to that social stigma. In some ways, Tilu compliments Lalee; where she is bitter and cynical, Tilu is hopeful and naïve.

It strikes me that the police officer Samsher Singh, the pimp Rambo Maity and Lalee’s most loyal customer Tilu Shau are incapable of having a proper relationship with a woman. They don’t see the women in their lives as individuals with separate thoughts, dreams and desires. They are instead reflections of themselves, a way to make money or an erotic fantasy. The only relationship of equals appears to be between the social worker Deepa and her husband Vishal. Did you set out to portray women and men as living in two entirely separate realities? If so, do you feel this is a true reflection of relationships in Calcutta today?

I don’t want to suggest that this is a generalisation of all relationships in Calcutta. But a culture heavily invested in the goddess/slut dichotomy, and where women have traditionally been associated with ideas of purity and treated as possessions, struggles with seeing women outside of their gendered roles, and especially as political subjects. The male characters like Samsher, Tilu and Rambo often are only capable of seeing the women in relation to themselves. Deepa and Vishal have a more equal relationship because they both bring a more cosmopolitan sensibility, due to their class privilege, education and exposure. This is not to say that equality between the sexes does not exist outside of privilege, but that one of the novel’s preoccupations is exploring women’s agency in situations where they seemingly have none.

Small Deaths is an accomplished debut that made me want to know more about the history of Calcutta and the people who live there. I’ve started listening to an amazing new podcast called Empire, which is thankfully filling in some of the many blanks. I’m curious to know about your next project. Are you working on something new?

I’m hoping to start on the next book really soon (fingers crossed), in the meantime, I’m finishing work on a novel I’ve been translating from Bengali to English, to be published by Seagull Books, and working on some short fiction.

Rijula Das received a PhD in Creative Writing/prose fiction in 2017 from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where she taught writing for two years. She is a recipient of the 2019 Michael King Writers Centre Residency in Auckland and the 2016 Dastaan Award for her short story ‘Notes From a Passing’, and ‘The Grave of the Heart Eater’ was longlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2019. Her short fiction and translations have appeared in Papercuts, Newsroom New Zealand and The Hindu. She lives and works in Wellington, New Zealand. Small Deaths was first published by Pan Macmillan India as A Death in Shonagachhi, was awarded the Tata Lit Live First Book Award and longlisted for many prominent awards including the JCB prize, and is in development for TV by Dryshyam Films. It is now out in hardback and paperback from Amazon Crossing and as a Kindle Edition.

Rijula Das received a PhD in Creative Writing/prose fiction in 2017 from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where she taught writing for two years. She is a recipient of the 2019 Michael King Writers Centre Residency in Auckland and the 2016 Dastaan Award for her short story ‘Notes From a Passing’, and ‘The Grave of the Heart Eater’ was longlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize in 2019. Her short fiction and translations have appeared in Papercuts, Newsroom New Zealand and The Hindu. She lives and works in Wellington, New Zealand. Small Deaths was first published by Pan Macmillan India as A Death in Shonagachhi, was awarded the Tata Lit Live First Book Award and longlisted for many prominent awards including the JCB prize, and is in development for TV by Dryshyam Films. It is now out in hardback and paperback from Amazon Crossing and as a Kindle Edition.

Read more

rijuladas.com

@RijulaDas

@AmazonPub

@PanMacIndia

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana’s wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on a crime novel set in California. Jessica Carson has returned to her conservative roots after working as a cop in Berkeley, one of America’s most liberal cities. The transition is not without difficulties. The police detective she’s replacing was involved in the 6 January riots and her estranged son has become immersed in Antifa.

karinsalvalaggio.com

Karin on Bookanista

@KarinSalvala