The land where Saturn reigned

by Mika Provata-Carlone“Each man is in his Spectre’s power” – these are words by William Blake that Marcello Fois deliberately places as the inscription over the gates of heaven or hell that was Sardinia as a private space of memory and genealogy, and as a very public constituent part of Italian society and history, a microcosm to distil and amplify the details and the traumas, the truths, transgressions and sins of a larger whole.

The Time in Between tells a story full of spectres, private ghostly dreams and the phantoms of a darker political and individual past. It aims to trace a pattern of belonging, a lineage of being, and a continuity of hope beyond the ravages of human actions or the rhythms of an unleashed modernity – against the march of time. It is the story as much of an interval, a break, as it is of a space suspended between history and timelessness. In 1943, war in Sardinia “had sounded like quarrelling neighbours, smashing plates, or a father raising his hand against the son who will not listen to him… This is how this war had been, a war they did not even dignify with the name of ‘war’. They preferred to call it a conflict, because the War, or Gherra had been the other war, from 1915 to 1918. Oh, yes, that had been a real war.” It is a privileged, insular viewpoint, granted not only to an island that is a “rock in the middle of the sea”, but also to people and families, communities, and perhaps even to Italy as a country. It allows for a revision of recent events, for a land of the Phaeacians that will render re-entry into life possible. Fascism is a nebulous category, an old-fashioned coat, almost quaintly worn by the older generation, and as prosaically discarded by the new ruling forces, Christian Democrats and Communists, clashing indifferently, even if zealously. The Russian front is the place of Italian martyrdom, of butchered and frost-bitten sons of the land, sacrificed by an unknown, un-Italian demon or dark lord who “sent us there… No one wanted to go. We had no choice.” The citizens of Nuòro, the Sardinian village whose ambition is to become a disproportionate and remarkable metropolis, will claim the choice to revise and forget, since “if the facts cannot be known, it means they never really happened at all.” “With the horrors of the abyss raging all around them, these people had taken refuge in a sort of rustic Switzerland, where they could argue about the distribution of the spoils and dream of expanding.”

Fois is curious about misplaced or displaced identities, about the loss of selfhood through tragedy, of the otherness of being an orphan – real or metaphorical.”

Fois’ countryside is also an intensely synesthetic world, where the landscape and the natural elements are prime movers not only of plots but also of souls, catalysts of the human condition, maps to being and destiny. A desolate, savage scenery that becomes a metaphor for a chart of both the human and the divine, the personal and the more universally historical. To this very physical and yet otherworldly space will arrive a stranger, a No One, a Ulysses figure who will claim roots, a past and a future, biographical details and everyday joys, banality and drama. Fois is curious about misplaced or displaced identities, about the loss of selfhood through tragedy, of the otherness of being an orphan – real or metaphorical – of a post-war reality that presses the question of the kind of identity that can or cannot be retrieved. His hero, metonymic and real, is Ulysses, who sought an Ithaca where infinity could find human embodiment, an antidote to the looming post-war reality that is “the very opposite of poetry… a new world… that seemed bent on rejecting eternity.” Are change and permanence mutually exclusive? Hardly ever, Fois constantly reminds us.

Vincenzo Chironi has been a No One as an orphan, and is now slowly retrieving the traces (or the figments) of his identity. There are Nausicaas and Cyclops on his way, the travails of restitution, recognition, return, survival (and even a suitor who may have to be sent on his way). There is an absolute faith in bloodlines, in the marks of genetic inheritance, but also doubt as to what truly constitutes affinity and individuality. “You have reached a land where everything is ancient, where taking and leaving can require thousands of years,” he is told, and Fois would perhaps like to suggest that at the beginning of things (a point every character seems particularly anxious to define, attain and ultimately evade), Italy was founded by a refugee who was given the status of native recognition and of inclusion into a race about to be born – Aeneas, fleeing Ilium, conquering Latium, instituting Rome.

Rebuilding, re-dreaming, re-living require confronting the question of the unbearably vivid presence of absence and death; of remembrance and forgetting; of returns that are promises of new beginnings but also engulfing labyrinths; and of a cyclicity in history and in individual destinies that confirms as much as it entraps characters and events in an inevitability of tragedy, simple joys and fatality. The war, malaria, a vicious attack of locusts and lesser or greater private dramas act as reminders of an almost Tolstoyan sense of history’s predestination, of the fallacies of historical analysis or in the belief in rational, humanly controllable dynamics and forces. And to an extent Fois does set out to produce a grand, if quieter, bucolic epic of his land, where the earth’s formation and stigmata, the natural elements, define psychology and history, where external factors and the inalienable bonds of blood ties reign supreme, as does the secret, inescapable code of affinity we attribute to them and which in Italy, especially in the south, can be almost more important than life itself.

The physicality of genealogical trees, of bodies and of nature replace character or socio-historical analysis, as though human beings and society formed part of the geological relief, and up until the very last sections of the novel there is a sense of impassive chronicling, of a simple objectivity that almost seems oblivious of its object. It is an objectivity of tragedy, of an ancient modern drama, that once fully enacted on the stage can only be articulated by an intrusive, anonymous, partial and revealingly confused tragic chorus, an ‘I’ that is multiple, diffused, problematic and interestingly empowering.

How is a man or a nation reborn? Through a process of erasure, of establishing a tabula rasa of which only god is capable? Through ritual cleansing, remorse, penitence? Through the demolition of all that existed before, and further divine creation ex hihilo? The Time in Between has lulls of beauty and stretches of tragic tension, mathematical sequences of questions and philosophical disputations of answers. It has moments of fragile and infinite humanity and shocks of stark cruelty and despair. The crisis and catharsis afforded are followed by an essay on life and death, on transformation and permanence, on the epic and the lyrical side of existence. One does not rage into the night, but walks to it slowly, resignedly, with the timeless wisdom of being but a link in a chain of lives, forming a genus, history, perpetuity. “Alright, let’s start again” are the novel’s last words.

Fois’ novel is distinctly new, original, skilled and ambitious; it is also an unmistakable homage to Grazia Deledda, to the power of literature to reignite a human soul and a communal psyche.”

Fois has written a tale of his people and homeland. He belongs to a generation of Italian writers who sought to revisit and revise the 19th-century genre of naturalism that was firmly topographical, perhaps even ethnographical, infusing it with critical force and a more urgent contemporary currency. He is also consciously establishing himself as the legatee of a lesser-known, yet crucial literary inheritance. Nuòro he tells us fleetingly, almost dismissively, was “home to a presumptuous bourgeoisie and intelligent shepherds, after which the world had been turned upside down and history with a small h had briefly crossed the main road and created a little insipient Sardinian Athens – projected onto the world stage by a Nobel Prize winner and rebranded arbitrarily by the Fascists as a city.” He does not tell us more, yet perhaps it is Fois who is now in his spectre’s power. Grazia Deledda (1871–1936) won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1926 – the second woman to win it, after Selma Lagerlöf in 1909, and one of 49 women on the Nobel roster all told. She was recognised by the Nobel committee “for her idealistically inspired writings which with plastic clarity picture the life on her native island and with depth and sympathy deal with human problems in general,” according to her citation. More importantly, she sought to find the words to speak the life of Sardinia and its people, to transcribe the landscape as a language of the soul. To break new ground by focusing on outcasts, on the voiceless, on transgression and obedience, on sin and affirmation. In a way, she dreamt of creating a myth of the local psyche, where Stanislavsky’s “I am being” could find poignant, even unsettling expression. Fois’ novel is distinctly new, original, skilled and ambitious; it is also an unmistakable homage to Deledda, to the power of literature to reignite a human soul and a communal psyche.

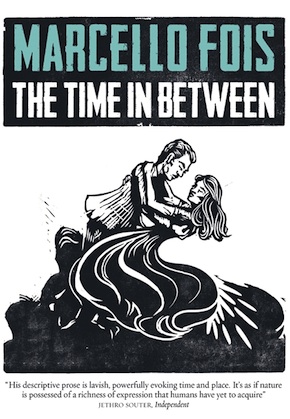

Marcello Fois was born in Sardinia in 1960 and is one of a gifted group of writers called Group 13, who explore the cultural roots of their various regions. He writes for the theatre, television and cinema, and is the author several novels, including The Advocate, Memory of the Abyss and Bloodlines. The Time in Between, translated by Silvester Mazzarella, is published in hardback and eBook by MacLehose Press.

Marcello Fois was born in Sardinia in 1960 and is one of a gifted group of writers called Group 13, who explore the cultural roots of their various regions. He writes for the theatre, television and cinema, and is the author several novels, including The Advocate, Memory of the Abyss and Bloodlines. The Time in Between, translated by Silvester Mazzarella, is published in hardback and eBook by MacLehose Press.

Read more

Author portrait © Daniela Zedda

Silvester Mazzarella is a translator of Italian and Swedish-language literature. For many years he lived in Finland, where he taught English literature at the University of Helsinki. He now lives in Canterbury.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.