Seabirds

by Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä

“These wry and winsome autobiographical sketches demonstrate the couple’s virtuosity in the art of living and their transmutation of that life into art.” Nancy Campbell, TLS

Of course I know the seabirds were here first! They’ve had their own registered territories for God knows how many generations, and it’s very clear they must hate us. They do screaming nosedives, beaks wide open. The terns are worst, real warriors, and their aim is perfect when they crap on us. These shimmering white symbols of freedom and distant horizons are driving us crazy. Tooti can’t do any graphic work without an umbrella, and when she jumps rope in the mornings they take it as a declaration of war. (I think it’s funny.) We can’t go swimming, can’t lay nets, can’t even go down to the boat. Never have I been so demonstrably hated!

And the common gulls! But how could they know that we scolded Brunström when he collected their sacrosanct eggs in his cap to make an omelette, or that we almost murdered a herring gull when he ate their chicks, or that we saved their stupidly placed nests when the water level rose, or that we collected gull food all winter, and in general that we put up with their horrible screeching on the roof of the tent at every sunrise?

But they are right. We came later and have no business being here.

It took us a long time to realise that the island needed to deal with its dramas on its own terms. Always the same. The herring gull strides down from his rock, saunters tranquilly from nest to nest and gobbles down the chicks, the poor babies’ legs stick out and twitch once or twice, the sky is full of screaming birds. Tooti rushes out with her pistol; it’s too late, once again, every time.

But there was one gull that wasn’t like the others. He wasn’t mad at us, and not afraid. His name was Pellura. Pellura strutted back and forth on the gangplank veranda outside the window, sometimes he’d tap on the glass and put on a kind of show.

Years ago on Bredskär, Papa had a gull of his own he called Pellura. This may very well be the same gull. They say gulls can live forty years, and Papa was over seventy when he died, so that must have been some time in the 1930s. In any case, Pellura was pretty old now, so no wonder he eventually got sick. There was something wrong with his throat. He could no longer howl with the other gulls, although he did his best.

Psipsina and Pellura ignored each other completely. They seemed almost contemptuous.

One of our morning rituals is to give the cat a shower. Here’s how it works. We brush our teeth at the corner of the house, the cat knows perfectly well what’s going to happen but sits and waits down on the meadow. We bang our brushes violently in our mugs and bellow, and only then does the cat take off like a rocket. But often as not we manage to give her a drenching.

Some people think we’re cruel. And childish to boot.

I tried to cheer up Pellura with a splash of water in his face, but he didn’t flinch. He had his territory on the other side of the lagoon and came over when I whistled. Next to the water barrel we had a short mast with signal flags spelling H, A, R and U, and he’d sit on the top to keep an eye on us. When it was time for the mast to come in for the night, he refused to fly home, just flapped his wings and held on tight with me shouting at the other end. It was a ritual.

Pellura grew brazen. One time he stole Tooti’s salmon sandwich right from under her nose and flew away with it, sick as he was.

“You spoil him,” Tooti said. She made a big deal of the fact that Pellura lured the whole gull colony over to us and worried that one of them might step in the bowl of nitric acid she had out on the gangplank. So Pellura got his meals around the corner, without any playfulness or finesse. But he continued to promenade back and forth outside my window. I hung up a bit of cloth so I wouldn’t have to see him, but I always knew he was there.

One night there was a storm from the south-east – why is it always south-east when something bad happens? I found Pellura the next morning. By then he was already full of maggots and had to be thrown out to sea.

The swallows came and, as expected, put on a great show – and then, presto, they were gone, leaving no promises behind. If only we could be like that and come back only when people no longer expect us! That would be so elegant.”

Every summer there was the same wait for the swallows. Brunström had told us that they nest only in houses where people are happy, but not if the house is painted with Valtti or Pinotex. The swallows came and, as expected, put on a great show, ripping through the air like shrieking knives, around the cabin again and again, to our admiration – and then, presto, they were gone, leaving no promises behind. If only we could be like that and come back only when people no longer expect us! That would be so elegant. Swallows nested in Ham’s old summer hats and on every possible ingratiating shelf and refuge that Tooti had nailed up under the eaves.

All birds are pretty, but few have a face like the eider – elongated, solemn, long-suffering and patient. She doesn’t move from her nest when you walk past, she stays where she is, looking self-controlled and inscrutable.

An eider hen nested for many summers under the rosebush in front of the cabin, and she did show respect for the cat. There were eider nests all over the island. We’d meet them at dawn in the ravine and wandering around the tent, conversing in their own quiet way. When the chicks hatched, their mamas led them to the water immediately, but without rushing, and they’d start swimming at once and loved the surf, or so it seemed. We noticed that eiders don’t count very well. One mama tows her young ones around the point, another mama crosses the procession with her babies behind her, and chicks break off without hesitation and follow a new mother. Sometimes muddled eider chicks would take refuge beside Victoria, which is large and protective. There were two abandoned chicks we called the orphans. They were always together and played in the lagoon and surfed the waves and grew up and lived happily ever after as far as I know.

© Tove Jansson

Extracted from Notes from an Island by Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä (Sort of Books, hardback, £12.99, October 2021)

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a writer and artist best known as the creator of the Moomin stories, which were first published in English seventy years ago and have remained in print ever since. Her life partner Tuulikki (‘Tooti’) Pietilä (1917–2009) was a graphic artist. Notes from an Island combines Tove’s spare, precise diary entries and vignettes – and extracts from the log of a maverick seaman named Brunström, who helped them make a summer home on the barren island of Klovharun – with subtle washes and aquatints created by Tooti of the island landscape.

Read more

tovejansson.com

@MoominOfficial

@SortofBooks

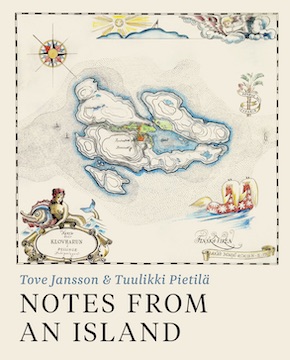

The cover of Notes from an Island (top) is a map of Klovharun penned by Tove’s mother Signe Hammarsten-Jansson (known affectionately as ‘Ham’)

Read more Tove Jansson on Bookanista:

Taking an interest in the meerschaum tram

Extract from the reissued The Memoirs of Moominpappa (Sort of Books, 2017)

Premonitions

Short story from the collection Letters from Klara (Sort of Books, 2017)

Keeping the Moomins above water

Interview with Tove’s niece Sophia, guardian of Moomins Characters, on the release of the film adaptation of Moomins on the Riviera (Vertigo Films, 2015)

The rain

Short story from the collection The Listener (Sort of Books, 2014)