The shovelist

by Orlando Ortega-MedinaGuillaume Morin stood at his kitchen window, peering through the falling snow. Across the street, two men in matching brown leather jackets were unloading boxes from a metallic blue Cadillac and lugging them into Suzanne Sillery’s old place.

“Stop staring! It’s not proper.”

Guillaume looked at his wife. She was seated at the kitchen table, pretending to focus on her daily crossword puzzle, but he knew she was as curious about Magog’s newest arrivals as he was. Anne made it her business to know everyone else’s.

“Diane Lapointe heard from the estate agent that they’re Pakistanis from Toronto,” she added.

“They don’t look like Pakistanis to me,” said Guillaume.

Anne set down the newspaper and glared at him over the rim of her glasses.

“When was the last time you saw a Pakistani?”

Guillaume shrugged and looked back out of the window. “What do you suppose they’re doing here?”

“Don’t know and don’t care,” she said, carefully writing a word into the puzzle. “I don’t much like the look of the pair of them.”

Guillaume poured himself a steaming mug of coffee and shuffled to the kitchen table.

“They look fine to me,” he murmured.

Anne set down the newspaper. “All I know is you’d better make sure they let you shovel their snow,” she said. “Because if it’s shovelry they need, you’re the one to do it.”

“That’s not a word.”

“What isn’t?”

“Shovelry. It’s not a proper word.” Guillaume glanced at the crossword puzzle. “And neither is this,” he added, pointing at the grid.

“Ha!” Guillaume’s wife said, swatting away his hand. “Another English lesson from Professor Over-the-Hill.”

Guillaume smiled, drained the last of the coffee from his mug, and stood tall. “In any case,” he said, “my arrangement was with Suzanne, not with them.”

“Maybe she told them about your arrangement.”

As he contemplated the pair, he vaguely wondered, not for the first time since he’d retired, just when did he and Anne get so old?”

Guillaume stretched his weary legs and returned to the window in time to see the young men haul the last few boxes on their porch and into the house. As he contemplated the pair, he vaguely wondered, not for the first time since he’d retired, just when did he and Anne get so old? Was it that long ago that they were moving into their own house as newlyweds? He had returned home early from the war, having suffered a major shrapnel wound. Fifty years later his hip still pained him, especially on cold days like this.

“Go introduce yourself,” Anne’s voice cut into his musing.

Guillaume narrowed his eyes at his wife. “Don’t you think we should at least let them settle in before we bother them?”

“Bother them? Guillaume Morin, you get yourself over there this second and don’t come back until they’ve agreed to let you shovel. We can’t afford to lose that money. Not with that miserable pension of yours.”

Knowing she was right, Guillaume sighed, pulled on his parka and homespun cap, and hobbled to the door. “Too old for this,” he mumbled as he stepped outside and braced himself against the penetrating cold wind. “A man ought to be someplace warm like Florida.”

He slogged across the snow-choked road until he reached the shining Cadillac, trying his best to look casual, hoping the young men might come out of the house again and save him the trouble of knocking on their door.

“What are you doing?” his wife shouted from the doorway. “Knock on the door!” She balled her hand into a fist and made a pantomime of pounding the air.

Guillaume waved her off and grumbled as he moved cautiously up the steps to the icy porch. Just as he lifted the brass knocker, the front door flew open and Guillaume found himself facing one of the young men. The knocker landed with a ringing thwack! – startling them both. The young man appeared to be in his 30s, wore his blue-black hair closely cropped and sported a smartly groomed goatee.

“Um, hello,” he said, staring curiously at Guillaume. “Can I help you?”

The other man stuck his head out the door. He was obviously much younger, clean-shaven with large, almond-shaped eyes. “Who’s this?” he said.

Guillaume attempted a smile but already his face felt frozen solid. He gestured across the street and managed the word “neighbour”.

“What was that?” the younger of the two said.

“He said ‘neighbour’,” said the other. “Is that right, sir? You’re our neighbour?”

Guillaume nodded. He regretted having crossed the street. Meeting new people, he reminded himself, was not his strong point. Fortunately, he thought, new people rarely appeared in this part of the Eastern Townships, least of all Pakistanis from Toronto.

“It’s freezing,” the man with the goatee said, moving back into the house. “Would you like to come inside?”

Firing a backward glance across the street to see his wife still standing in the doorway, Guillaume nodded and crossed the threshold into Suzanne Sillery’s former home. The young men ushered him through a maze of boxes, bags and suitcases into the living room. Guillaume looked around but didn’t see anywhere to sit.

“I’m Jake Abulafia,” the goateed man said. “This is my boyfriend, Ronny Dwek.” He thrust his hand toward Guillaume. “And you are…?”

“I’m the shovelist,” Guillaume replied, shaking the proffered hand.

The two young men exchanged a glance.

“I’m sorry,” Ronny said, raising an eyebrow at Jake, “you’re the what?”

“The shovelist. I do the shovelling. For the snow.”

“What do you mean?” Jake said. “They have snowploughs here, I’m sure.”

Guillaume shook his head. “For the streets, yes, of course, but I’m the shovelist for this house – front porch, side yard, backyard, deck.”

“I’m going to make some tea,” Ronny said with a curt shake of his head. “Would you like some?” He moved to the kitchen without waiting for an answer.

“We’ve always shovelled our own snow actually,” Jake said. “Thank you anyway.”

“But,” Guillaume reddened a bit and he cast his eyes about the room for a moment, wondering what would happen to his own house when he and Anne were gone. He had heard that Suzanne’s children had sold most of her beautiful furniture and all her paintings, clearly more interested in the cash than keeping what their mother had worked so hard to acquire. Now, nothing of substance remained. Only the shell of a house filled with boxes belonging to new owners. Who would move into his house when he was gone, he wondered. Someone from the townships? Or strangers?

Guillaume was suddenly aware that Jake was staring at him. He coughed into his glove and wiped it on the seat of his trousers. “I always shovelled for Madame Sillery. The woman who lived here before you,” he said, looking at the empty walls. “She painted,” he added.

“Did she?” Jake said distractedly, wondering where Ronny had got to with the tea. “You know, we have quite a lot to do at the moment.” He pointed at the unopened boxes. “Perhaps we might speak about this again, some other time. But stay for a cup of tea first. It’s dreadful out there today. We’re not used to seeing this much snow.”

Guillaume stared hard at the floor, praying for a solution to this dilemma. He didn’t want to explain to his wife that he had lost the contract. She would blame him throughout the long winter for not selling himself hard enough. He could imagine her nattering at him all day, all night, that if someone needed shovelry, then he was the best man around and it was all a matter of his convincing these young men.

“Well,” he answered, his legs stiffening from standing so long in one position, “I don’t guess you get much snow in Pakistan.”

Ronny was just walking into the living room carrying a brass serving tray on which he balanced three teacups, a teapot and a creamer. He cocked his head and stared strangely at the old man. “Pakistan?”

…

“Did you get it?” Guillaume’s wife said, as he hung his parka on one of the coat pegs.

Guillaume pulled off his mittens with his teeth, hobbled over to the blazing fireplace and held up his hands against the warmth.

His wife crossed her arms and glared at him.

“They’re not Pakistanis,” Guillaume said, staring into the flames.

“What?” The woman took a step toward Guillaume.

“Remember, I told you they didn’t look like Pakistanis, and you said, how would I know?” he said, half-turning to peer at his wife out of the corner of his eye. “Well I was right. They’re not. They’re some kind of Jewish or Spanish. Work for the government.”

She rolled her eyes at him. “I don’t care where they’re from. Did you get the contract or didn’t you?”

“Yes, Anne, I got it,” Guillaume muttered. He creaked toward the bedroom before stopping to turn back to his wife, touching her cheek. “Don’t worry, poppet. We’ll be all right.”

…

“What’s that noise?”

Jake rolled over in bed and opened one eye. Ronny was sitting bolt upright, his hair sticking up like a black jaggedy cockscomb.

“What noise?”

Ronny raised a finger and cocked his head. A moment later, a faint scrape-scrape-scraping sound floated into the room. Ronny instantly leapt out of bed, flung back the blinds and looked outside.

“That crazy old man’s shovelling our driveway.”

He rapped on the window several times, then turned to Jake, a look of exasperation on his face. “He’s ignoring me.”

Jake glanced at the clock on his nightstand and shook his head. “I’m sure he can’t hear you. It’s 6:30 in the morning, for fuck’s sake, Ronny, go back to sleep.”

“But you told him no,” Ronny said, looking back outside at the old man, who was moving slowly to the side yard, the shovel trailing behind him leaving an impotent rut in the snow.

“I’ll talk to him later.” Jake fluffed his pillow and pulled it over his face. “Come back to bed,” came his muffled voice.

Ronny quickly padded around to Jake’s side of the bed and yanked the pillow off his head.

“You’re not going to let him shovel after you told him not to, are you?”

“Why not?” Jake said, prying the pillow from Ronny’s grip.

“Because it’s not right! People can’t just go doing whatever they want on other people’s properties because they feel like it.”

“Maybe he thought I said he could do our shovelling.”

Ronny marched to the closet, extracted Jake’s bathrobe, and held it out to him. “Go tell him to stop.”

Ronny knocked vigorously on the glass door and Guillaume looked up at him, lifting a mittened hand in a weak attempt at a wave.”

Jake sat up and rubbed his face. “I have an idea,” he said, “Let’s just let him do our shovelling today. It’ll save us the time and trouble and will likely do the old guy some good, too.”

Ronny let the bathrobe drop to the floor and stormed out of the room. He raced down the stairs to the sliding glass door at the back of the house. Guillaume was starting to clear the snow from the steps leading up to the back deck. Ronny knocked vigorously on the glass door and Guillaume looked up at him, lifting a mittened hand in a weak attempt at a wave. Ronny signalled him over to the door.

“Good morning,” Guillaume said, his breath billowing through the narrow opening. “It’s a cold one today.”

Ronny looked at the shovel then back up at the old man. He looked somehow different in the blue light of early morning. He could see that the old man had been once handsome in his youth, but his face was now deeply lined and chapped an angry red. A rheumy film was starting to cover the iris of his left eye, and his right eye was shot through with spidery veins. The lanky old man would have stood over six feet tall if it were not for a noticeable stoop, a sagging of the head as if his neck could no longer support its weight. Despite his posture, the old man carried himself with a clear sense of dignity.

“You’re shovelling our snow,” Ronny said quietly.

The old man nodded, “I’m the best shovelist around.”

“But we told you not to.”

Guillaume looked down at his boots for a moment, then looked back up at Ronny and pulled himself to his full height, clearing his throat. “This is a sample of my work. For free, of course – to see if you like it. You can let me know tomorrow if you’re pleased with the job.” He continued to shovel, as though the matter were settled.

***

Some time later, Jake came downstairs in his bathrobe and stockinged feet to find Ronny sitting on a box in the living room, staring thoughtfully into a cup of Earl Grey. “I was beginning to wonder what happened to you,” he said.

Ronny took a considered sip, then rose from the box to make his way into the kitchen. “We’re going to have to go out for breakfast,” he called over his back. “All the cooking stuff is still packed away.”

“Right,” Jake said, following him, “but what about the old man? Did you talk to him?”

“I did,” Ronny said, staring out at the back deck, now completely cleared of snow. “I told him it was all right. He can do our shovelling.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Like you said,” Ronny put the tea kettle on the stove, “it will save us the trouble, and will be good for Guillaume.”

“Who?”

“Guillaume. His name is Guillaume Morin. I realised while I was outside that we never got his name yesterday.”

Jake looked out of the window. The removal of the snow was irregular at best: perfect in some spots, downright sloppy in others. He looked back at Ronny, a doubtful expression on his face.

“Guillaume?”

“Guillaume, and Anne, his wife. You know, it’s not a bad job for an old guy.”

Jake looked out the window again, then shook his head and moved to the kitchen to pour some boiling water into the teapot.

“We can always fix it later,” Ronny added. “It’s not a big deal.”

Jake opened his mouth, calculating a clever retort, when he caught sight of Guillaume out their front window, his shovel slung over his shoulder, striding across the road toward his house. He looked back at Ronny with a slight shrug of his shoulders.

“I guess we should finish unpacking these fucking boxes.”

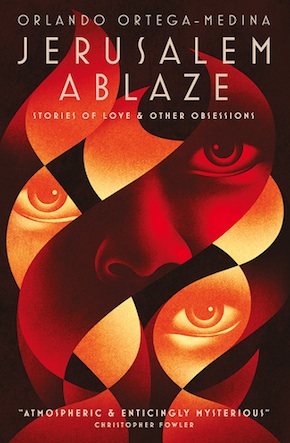

From the collection Jerusalem Ablaze.

Orlando Ortega-Medina was born in California of Judeo-Spanish descent via Cuba. He studied English Literature at UCLA and has a Juris Doctor law degree from Southwestern University School of Law. At university he won The National Society of Arts and Letters award for Short Stories. He is now a British national and resides in London, where he practices US immigration law. Jerusalem Ablaze: Stories of Love and Other Obsessions, his first published collection, is published by Cloud Lodge Books.

Orlando Ortega-Medina was born in California of Judeo-Spanish descent via Cuba. He studied English Literature at UCLA and has a Juris Doctor law degree from Southwestern University School of Law. At university he won The National Society of Arts and Letters award for Short Stories. He is now a British national and resides in London, where he practices US immigration law. Jerusalem Ablaze: Stories of Love and Other Obsessions, his first published collection, is published by Cloud Lodge Books.

Read more.

orlandoortegamedina.co.uk

@OOrtegaMedina

Also by Orlando Ortega-Medina in ‘Favourite Stories’

Yukio Mishima: ‘Swaddling Clothes’