Stories from the front

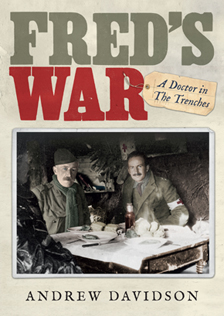

by Andrew DavidsonAndrew Davidson’s Fred’s War tells the story of the 1st Cameronians, who achieved notoriety for selling the Great War’s earliest frontline photographs, and of the author’s grandfather, one of the first medical officers to win the Military Cross. He blends Fred’s photographs and those taken by his friend Lieutenant Robert Murray and others with contemporary narrative to piece together the stories behind pictures that have passed through the family for three generations; describing the conditions the men served in, the battles fought and horrors witnessed by a band of brothers who later proudly dubbed themselves ‘Old Contemptibles’. He selects ten other revealing works about the war.

Partialities first. I fell into this through three photo albums left by my grandfather which revealed an extraordinary episode in his life: the eight months he spent as medical officer with the 1st Battalion, Cameronians, fighting the Germans at the beginning of World War One. That initial period – sailing to France, marching to Mons, being driven back to Soissons, fighting towards the Channel, trying to flank the enemy, entrenching south of Ypres – is a very different war to the one that is now familiar to many. The British Expeditionary Force was the professional army, upbeat and uncynical, looking forward to dispatching the Germans in a short campaign. Later came Kitchener’s volunteers, and then Britain’s conscripts, with a concomitant fall in morale and a sapping of belief in any justice of the cause. But my grandfather’s war was a different fight with men still full of hope, out on a lark, initially anxious it would be over too soon – and totally unprepared for what ensued. Many of the books that most intrigue me cover that first part of the war, the lesser-known one, and focus on the areas I find fascinating: medicine, photography, the individual, the quirks of regimental behaviour. Bigger books on why the war happened became less interesting as I burrowed down. Apologies in advance for leaving the obvious, large-scale histories off the list, and the best-known novels, but they’re easily found in bookshops. Some of these aren’t. They are niche, or old, or discarded, and frequently take on a subject in an odd way, and are all the more rewarding for that.

Morale: A Study of Men and Courage by John Baynes (Cassell)

One of the most eye-opening books you can read about what it was like to serve in an Army regiment in 1914. Written in the 1960s by a serving officer in the Cameronians, it dissects with a sociologist’s precision the bonds formed in military units, unpicking everything from the peculiarities of Mess protocols – never discussing women by name, never starting a conversation with a senior officer in your first few months – to the backgrounds of officers and ranks pre-war, including their hobbies, diet, and even sexual habits. Now imagine all that plus a sober, sad retelling of the massacre at Neuve Chappelle, where the 2nd Battalion of the Cameronians were all but wiped out in one of the key early battles of WWI – it is a sad portent of everything to come.

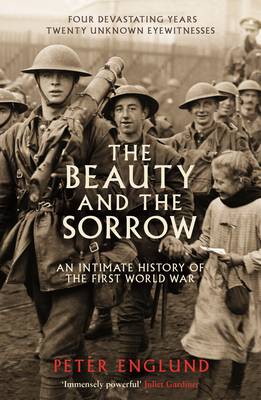

The Beauty and the Sorrow by Peter Englund (Profile Books)

The Beauty and the Sorrow by Peter Englund (Profile Books)

The cleverest of books, interweaving multiple viewpoints of 20 ‘unknown witnesses’ involved in WWI at all levels – soldiers, nurses, politicians, civilians, on all sides – using diaries and memoirs as a base, then augmenting that by giving each a voice, as if the author has climbed into their heads and seen it all through their eyes. It inevitably suffers from being bitty, but is so sensitively written by Englund, a Swedish academic, and elegantly translated by Peter Graves, that you often feel you are living the lives presented. “I want to depict the war as an individual experience,” writes Englund in the Foreword. And he succeeds.

Private Pictures by Janina Struk (I.B. Tauris)

It starts with Abu Ghraib, then moves back through how soldiers use the camera, what they take, why they take it, and how it has changed, war by war. Struk, a photographer and lecturer, writes a smart chapter on WWI and the push by American manufacturers to get the new ‘vest-pocket’ folding cameras into solders’ hands, opening up new lines of sight on how ad campaigns in the press helped form views on where a camera can be taken. ‘Tourists in uniform’ sums up an approach rather different to that later adopted by the Nazis, who happily recorded their own atrocities. It is extraordinary, powerful stuff.

No Hero This by Warwick Deeping (Cassell)

Deeping was a celebrated storyteller of the 1920s and 1930s who published over 50 novels and has since sunk into obscurity. This 1936 book is deeply felt, not least because the author served as a medical officer in WWI, and accurately captures the blether of the officer class, the dependency on the men around you, and the danger that one idiot in command can cause. Martin Amis knowingly poked fun at Deeping, who rarely stopped to polish a phrase, in his novel The Information – his unsuccessful protagonist is working on a never-completed essay on the over-prolific author – but No Hero This is important, not least for its strong vein of pessimism about the war, and the strategies pursued. It is, however, ruined by the overt racism with which Deeping deals with a bolshy ‘Hebraic’ East Ender promising class war at the end. Revealing, in more ways than the author intended.

Doctors in the Great War by Ian Whitehead (Leo Cooper)

And if you cannot get enough doctors in WWI, this may be the book for you, a diligently crafted tome on every aspect of becoming a doctor in the Royal Army Medical Corps of 1914. Incorporating training, administration – lots of that as the Army prided itself on its organisation – and practice in nine readable essays and a conclusion, it is the best book on the mechanics of medicine during WWI that I know. It doesn’t, however, tell you how the RAMC allocated Medical Officers to specific regiments. I suspect it was often on a ‘Who fancies it?’ basis.

The War the Infantry Knew by J.C. Dunn (Abacus)

Privately published initially (like so many of the best books from the period), this day-by-day chronicling of first-hand accounts from members of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Welch Fusiliers, was put together by Dunn, their Medical Officer, to correct the perceived exaggerations promulgated by the battalion’s two bestselling officer-authors, Robert Graves (Goodbye To All That) and Siegfried Sassoon (Memoirs of an Infantry Officer). It’s as fat as a brick and rich in detail, and while Dunn doesn’t come over as a particularly sensitive or perspicacious doctor – he is rumoured to have touted a pistol and taken over the battalion when other officers were invalided out of battle – it is excellent on the fug of war. The Welch served side by side with the Cameronians on the Bois Grenier front. Suffice to say, they didn’t like each other.

War/Photography by Anne Wilkes Tucker et al. (Yale University Press)

Essentially a collection of essays and pictures to accompany the Houston Museum of Fine Arts’ exhibition War/Photography: Images of Armed Conflict and Its Aftermath, it analyses the impact of photographs taken in war over different centuries and across different cultures. For its breadth alone, it is fascinating – and every photograph chosen is absorbing. As gallery director Gary Tinterow writes in his Foreword, the pictures stand “as a testament to the extraordinary power of photography to capture and intensify human experience.”

Her Privates We by Frederick Manning (Serpent’s Tail)

All the cussing and cynicism and pessimism that pervaded the conscripts’ war is here in Manning’s groundbreaking account of what it was like to be a reluctant NCO in the face of the horror and tedium of trench warfare. A literary hack in London, Manning served initially as a private, was regularly promoted then busted back again for over-drinking, and wrote Her Privates We (a quote from Hamlet and knowing dirty joke) for friends after the war, before publishing it pseudonymously as Private 19022 without the swearing. Now it’s available unabridged, unexpurgated and brilliant in its bloody-minded anger. “We’re fightin’ for all we’ve bloody got” says a soldier discussing the reasons behind the war. “An’that’s sweet fuck all,” ripostes another.

Shots from the Front by Richard Holmes (Harper Collins)

Once picked up, this compendium of great British photographs from WWI is hard to put down, interwoven with perspicacious essays about the war by historian Holmes. However it’s light on the technology of cameras; and what of the men in the pictures – who were they? Wouldn’t it be great if we knew what had happened to them before and after the picture, why they were there, what battles they were about to face? That was what I thought before I started Fred’s War – my grandfather did the rest.

‘Mademoiselle d’Armentières’ by Anon

This is for Fred. Sorry, not a book but a living, morphing, extraordinary piece of sung literature that captures generation after generation. Based on a old French marching song, and originally titled ‘Two German Officers Crossed The Rhine’, it became WWI’s most popular, filthy soldiers’ song, was resung in WWII in an even filthier version, then recrafted again in yet filthier form – if possible – as a rugby club song. Perhaps now, in more PC times, it is finally losing its draw. But it’s hard to think of ‘Mademoiselle’ without humming the tune, and it’s one of the few works of literature that everyone is invited to improve. And I’m sorry, but the simile involving the Maxim Gun does always make me laugh. My grandfather, stationed in Armentières in February 1915 when it initially took shape, heard it first, so hats off to him and inky-pinky, parlez-vous.

Andrew Davidson is an award-winning journalist whose previous books include Bloodlines, an anatomy of daily life at St Thomas’s Hospital, and Smart Luck, an anthology of his interviews with well-known entrepreneurs for the Sunday Times. Fred’s War is published by Short Books.

Andrew Davidson is an award-winning journalist whose previous books include Bloodlines, an anatomy of daily life at St Thomas’s Hospital, and Smart Luck, an anthology of his interviews with well-known entrepreneurs for the Sunday Times. Fred’s War is published by Short Books.

Author portrait © Paul Vicente

Browse some of the images from Fred’s War on Facebook:

facebook.com/FredsWar