The story of their history

by Mika Provata-CarloneThe experience of lost places of belonging, of lost states of existence, together with the tenacity to defy and resist both loss and non-being, are deeply ingrained in the Russian language: thanks to Maxim Gorky, a term such as Бывшие люди, or ‘former people’, would come to acquire an eerily tangible corporeality, reality, and even harrowing normality. There is a stinging cynicism and a butterfly effect of connotation in these words, derived from the title of one of Gorky’s short stories, which was translated, with unflinching matter-of-factness in English as ‘Creatures That Once Were Men’. The word Бывшие contains in it a pastness, an ineluctable finality, that is overwhelming in its terminality, but also deeply evocative in its timelessness: applied to people, it presupposes an ancientness that is as removed and alienated from the here and now, as it is indelibly embossed on it. It contains everything and nothing all at once: the colossal presence of a history of troubled continuity, and the titanic gesture of violent dismissal, of outright annihilation, that a particular moment in time deemed necessary in its ideologically intoxicated fervour. More than a struggle between Ancients and Moderns, the word Бывшие, and the state it embodies, prefigure the battle for a Paradise Lost, the dire angst as to whether it can ever be Regained.

Gorky’s ‘former people’ were from the start much more than just unfortunates who had fallen on hard times, or the dramatic victims of riches-to-rags personal sagas and catastrophes; they were the emerging emblems of a totalising process of erasure that transcended the personal, the ontological, or even the historical. In the fast evolving, all-dominating technocrat language of the Soviets, ‘former people’ became literally just that, the people of a former reality, who could no longer be allowed to exist. These ‘lasts’, as they appear in the Russian, English and French titles of Nina Berberova’s novel The Last and the First, are the multitudes who were declassed, displaced, and pragmatically decimated by the 1917 Revolution and its aftermath. There would be ‘former people’s’ public court trials, ‘former people’s’ arrests and deportations to Siberia, more thorough and systematic cleansing of ‘former people’ during the Great Purge, and ultimately an officially defined, nearly 35-million-strong category of ‘former people’ (and current undesirables). In France alone, 400,000 such ‘former people’, spanning every subdivision and minor subsection of the species, would seek a place of belonging (if possible), of exile (if permitted), of suspended, transitory or outright spectral being (in most cases). The efforts throughout, of those “that once were men”, those last remnants of what could no longer exist, were to outlast the process of their own forced disappearance and its mechanisms of near-extinction.

With the background of its history, the story takes on a momentous poignancy – and especially an almost portentous currency and resonance readers cannot fail to recognise for their own fates and destinies today.”

The history of this ‘formerness’, and the individual stories that were its vestiges, transpierced each individual Russian émigré life, and resonated across this involuntary diaspora in a booming, unforgettable, petrified whisper. It is this rising whisper and the dread behind it, together with a pervading sense of stubborn resignation and resilience, that underlie and inform Berberova’s debut novel. Written in Russian in Paris, it first appeared in serialised form in 1929, in the famous literary journal Sovremennye zapiski – Contemporary Papers, which would also publish early Vladimir Nabokov, the Nobel Prize-winning Ivan Bunin, the Comrade Count (and Turgenev’s relative) Aleksey Tolstoy, and George Steiner’s friend Andrei Bely. In the whirlwind of the early post-revolutionary years, Contemporary Papers occupied that nebulous space of revolutionary counter-revolutionism, advocating agrarian socialism with neo-romantic, Tolstoian twists. It articulated hope and despair, confusion and enlightenment, the mottled crowd of humanity, ideological positions and experiences that made up both its authors and its readership. In 1930, Berberova’s novel would see publication in one of the most overlooked, yet also remarkable of Parisian maisons d’édition, Jacques Povolozky & Cie., whose owner and founder was also a gallerist who hosted Modigliani, Picasso, Picabia and Soutine in his La Cible. Everyone who was anyone came to Jacques and Hélène Povolozky’s vernissages; to be published by them was no mean feat, yet it also hints at the bleak insularity of the émigré predicament: it took a fellow Russian to publish a Russian brother or sister. Berberova would for long feel a certain resentment towards the French: not a single publisher would accept her books for publication until Hubert Nyssen and his Actes Sud in the early 1980s, less than ten years before her death.

One can read Berberova’s novel without seeking to grasp at the countless threads of personal or public narrative that it evokes and contains, the history that frames and infuses it, and still be gripped by the quandary and tragic resilience of its humanity. With the background of its history, the story takes on a momentous poignancy – and especially an almost portentous currency and resonance readers cannot fail to recognise for their own fates and destinies today. The Last and the First evinces both talent and awkwardness, yet bear with it through its first slightly overburdened and wavering pages, and you will find yourself in the midst of a tale where myth and human plight fuse into one unignorable plea for compassion, for a careful assessment of history and its warning signs, for the symptoms of the madness and frenzy that can strike nations as well as individuals.

There is proper literary craftsmanship in Berberova’s writing, a respect for writerly conventions, traditions and precedent, even when a certain inclination for anthropomorphic qualifiers and storytelling artifice, for superimposed, serial attributives, and perhaps some insecurities in the translation, may weaken on occasion what is a fine narrative canvas. Her novel contains almost every recognisable Russian trope and character: the Tiresias figure who is both a living saint and a Dostoyevskian shadow, the Anna Karenina anti-heroine, the Tolstoian idealist, the Turgenev love subplot, the Chekhovian paralysing ecstasy and epiphany, the Gorkian unflinching realism. It features agents provocateurs, ruthlessly ambitious politicos, half-hearted double agents, demi-monde lost souls, and noble, self-denying heroes. It has polished style and lyrically folkloric, throbbing authenticity, a quick pace, and the hard oneiric quality of Nabokov’s Pale Fire. Its story is as complex as it is simple: the Russians who fled also yearned to return; they longed to settle as much as they were compelled to err and wander: they would often describe their state of existence as “sitting on their suitcases”, ready to leave for the homeland, for a return that was as much a chimeric dream as a lifeline of despair; the Russians who claimed the new Russia as their own could neither tolerate nor afford to let go of these ‘former’ Russians, who threatened to become ‘first’ in a new Russia of their own.

It is a no-man’s land of forced exile, an impossible tension between assimilation and belonging, alienation, depersonalisation, cultural, historical and very real vanishing of actual lives. Through a seemingly classic format of a neo-romantic, neo-realist account told with grand narratological poise, Berberova subtly delineates a substantial spectrum of émigré psychology, contributing importantly to what would become an established exilic genre. Halfway through the novel emerges an unmistakable j’accuse, meting out historical and individual blame, demanding both agency and responsibility over mere fate or improvidence. It raises questions of ideals over ideologies, of integrity over racial purity and categorisation, of clarity of vision over irony, cynicism or dejection. It above all urges – The Lost and the First is unmistakably littérature engagée – for action over reaction, for resolve and solutions over revolutions, but also over a certain nostalgie de la boue. Having lost a country, a history, a place of roots and belonging, Russian émigrés feared the much more fatal loss of a Russian soul. Russian revolutionaries in turn feared that émigrés might in fact counterclaim that same soul they were so intent to call exclusively their own. As The Lost and the First hints menacingly, it was a battle to the end, a struggle of life and death. Stripped of mythologies, romanticism, fervour and grand proclamations, the pursuit of a social and individual utopia as the Soviets saw it emerges as a chilling and far more unsettling mirage or nightmare.

As we envision or are faced with our own fervent and determined revolutions and world convolutions, the question of lasts and firsts, of pasts and futures, has a particular urgency.”

The émigré times are also the interwar times, and the further implications and permutations of devastation, disruptiveness, righteous discontent, stolen dreams, boiling anger, the inherent supremacism of disorder politics and anti-status-quo rebellions, the extremism of radicalisms, but also the obscurities of median ways, surfeit and predicate Berberova’s story. Knut Hamsun, the Circassian genocide, War and Peace, the Zemgor committee, even figures such as Pitirim Sorokin or Mayakovski, all haunt and inhabit the pages of the novel and the minds of the characters. Ultimately, The Last and the First offers a stark depiction of lives under the surface, of disintegrating shadows, but also of lives fighting for survival and for a future. It is a troubling tracing of the various politics of manipulation, coercion, indoctrination and misinformation of the times (of so many other times), which take advantage of destitution and suffering, pain and rootlessness, of despair and the longing for hope, in order to produce the multiple of horrifying and catastrophic -isms that would set the world ablaze, in a systematic campaign to eradicate humanity and its civilising principles and structures, from left to right.

Nina Berberova left France for the United States, where she would join that formidable and utterly heuristic first generation of Russianists or Slavists in the corresponding nascent departments of many American universities. She would teach at Yale and then at Princeton, offering, quite literally, an experience of total immersion in both language and culture, in a way of being and of perceiving. Her novels are finally receiving the attention they deserve, published by New Directions and now Pushkin Press, and they should be read alongside Amor Towles’ A Gentleman in Moscow, Rachel Polonsky’s Molotov’s Magic Lantern, Douglas Smith’s Former People: The Final Days of the Russian Aristocracy¸ Alexandre Vassiliev’s arguably more eccentric yet poignant Beauty in Exile and, for a more sobering parallel vision, Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. As we envision or are faced with our own fervent and determined revolutions and world convolutions, the question of lasts and firsts, of pasts and futures, has a particular urgency, and our own whirlwinds may sometimes deprive us of that clarity of vision that only hindsight and a closer scrutiny of history can perhaps afford. Read Berberova’s novel as such a parallel journey and parable, and you will put it down full of new and old questions – and hopefully some hints towards a few restorative answers. Berberova’s autobiography was entitled The Italics Are Mine – perhaps hinting that the italics of history, of stories, of actions, and of our own agency and conscience, are always there, if we would only pause and see them, acknowledge them, truly reflect upon them.

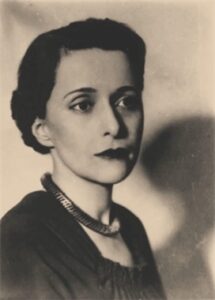

Nina Berberova (1901–1993) was born and raised in St Petersburg. She left Russia in 1922 and lived in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Italy before settling in Paris in 1925. There she published widely in the émigré press, and wrote the stories and novels for which she is now known. She emigrated to the United States in 1950 and eventually took up academic posts at Yale and Princeton. In France she was honoured as a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The Last and the First, translated by Marian Schwarz, is published in paperback by Pushkin Press.

Nina Berberova (1901–1993) was born and raised in St Petersburg. She left Russia in 1922 and lived in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Italy before settling in Paris in 1925. There she published widely in the émigré press, and wrote the stories and novels for which she is now known. She emigrated to the United States in 1950 and eventually took up academic posts at Yale and Princeton. In France she was honoured as a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. The Last and the First, translated by Marian Schwarz, is published in paperback by Pushkin Press.

Read more

@PushkinPress

Marian Schwartz translates Russian classic and contemporary fiction, history, biography, criticism and fine art. She is the principal English translator of the works of Nina Berberova and translated the New York Times bestseller The Last Tsar by Edvard Radzinsky, as well as classics by Mikhail Bulgakov, Ivan Goncharov, Yuri Olesha, Mikhail Lermontov and Leo Tolstoy.

marianschwartz.com

Pushkin Press: Marian Schwartz on The Last and the First

@mbs51

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/