The supper

by Nilton Resende

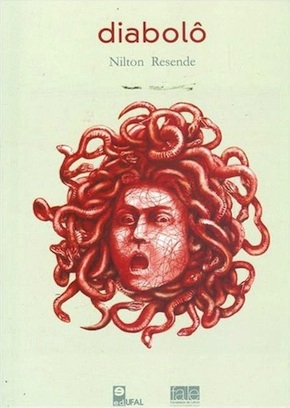

This story was first published in Portuguese as ‘A ceia’ in the collection Diabolo (Edufal, 2011)

I bite the cookie I’d slowly brought to my mouth; it breaks, like bones being crushed. I grind it and picture the lattice pattern on its surface coming apart, reminding me of the game my grandfather taught me and invited me to play on many afternoons. Cookie, lattice, crushed bones. I bite down and feel I’m chewing up the old man, crumbs coming out the corners like fingers trying to escape.

I was up on the table, masturbating in front of the painting of the gypsy. She was lying back on a divan, one hand caressing her nipple, the other buried beneath a purple drape. I was turned on imagining her fondling herself, making herself wet; and was moaning when he came into the room and yelled at me to get down.

I stiffened. Holding my little hard-on with one hand, I gave a dance wave with the other, then turned toward him in a continuation of the dance, my look stern. Pouting provocatively, I blew him a lewd kiss and yanked back the hand holding my dick, showing off its state of arousal.

He grabbed my arm, forcing me off the table. Holding tightly, pulling me down, he said he was going to tell my parents when they got back from the movies. Adding that this time they’d find out just what a hellion they had in the house.

“You’ll be sorry if you do,” I said through my teeth, pulling myself from his grasp and snatching my shorts from the table. I stood, sashaying toward the bathroom, a grin stamped on my face as my body shook with laughter at the trembling old man.

I could see that he was unnerved, as I passed the mirror and paused, keeping my eye on him. He didn’t move, just looked at me with an expression that to this day I don’t know whether to call hate or pity. I fixed him with a glare and with a mocking cry ran into the bathroom.

I leaned my face against the wall and violently rubbed up and down until it hurt. When my skin started to burn, I gritted my teeth and rubbed even harder.”

I remained there, in silence and semi-darkness. I lingered a few minutes, getting dressed, when he came to the door and said softly: “Today, I tell all.”

I got scared right then, confused for a moment. But I soon calmed down and finished dressing in the midst of my brilliant idea: I leaned my face against the wall and violently rubbed up and down until it hurt. When my skin started to burn, I gritted my teeth and rubbed even harder. Finally, I rammed my forehead against the toilet and smiled when I felt a small lump protruding. I cleaned the wall, red from my bloody scrapes, left the bathroom, and carefully tiptoed by the old man’s room to see if he was sleeping. I went back to the dining room, turned out the light and went to my bed. Not before admiring myself in the mirror. I was proud of myself, and an inscrutable smile took shape. Just like the one when I stuck a rat in the old man’s bed, containing my laughter when – I’d already gone back to my room – he screamed for help because something had bitten him. My mom and dad ran to see what had happened and had to hold the old man when they found him sitting in bed, eyes bugging in disbelief at the crushed red mass in his hands. I appeared in the doorway and asked almost innocently, “Grandpa… What is it, Grandpa?” But he didn’t answer, sitting naked on the bed, my dad trying to get him to stop trembling, my mom covering him with a sheet, his legs skinny and black, almost white only the patch of grey hair I could see framing his shrivelled sex.

The next day, at the breakfast table, he grabbed my hand – my mom and dad were in the kitchen – squeezed, and asked sharply: “Was it you?” “Mom!” I shouted. As soon as she appeared, he let go. I felt powerful. “What is it?” she asked, coming over. “Mom,” I replied sweetly, “will you fry me an egg?”

She turned. Looking into his eyes, I wanted to smile.

I don’t know what went through his head the days that followed, but he seemed to have forgotten the rat. As well as the slip he’d taken a few days before because I’d waxed the floor in his doorway, causing him to fall and hit his head. And his snuff – into which I’d mixed ground black pepper.

He was calmer. We’d play in the afternoon. He’d draw the lines on paper, and we’d place bean husks on the points to see who could lock in the other. But the night I was up on the table, I realised: he was resolved to talk.

I went to bed. I lay down and waited for my parents to arrive and go to sleep, but I didn’t catch a wink. In the morning, I heard whispers in the kitchen. “He’s no good,” I heard my grandfather say. “Respect my son,” said my dad. “Respect my son or you’ll be out of this house.” “But I’m your father,” the old man said, his voice hoarse. And my dad replied: “But he’s my son.” And right then my mom shouted that it couldn’t be true, I was only a child!

Curled up and sobbing, I had a few stronger coughing fits when my dad got to the room. He came in and gruffly removed the pillow covering my head. To this day I haven’t forgotten the terror on his face.”

“Call him!” my grandfather said. “Call him,” he repeated, lowering his voice. “Ask him in front of me if what I said is a lie. Ask! I can’t believe he’ll lie.”

That’s when I cried. I gave a pretty loud first wail, then toned it down, my quivering body curled up in the bedcovers. Curled up and sobbing, I had a few stronger coughing fits when my dad got to the room. He came in and gruffly removed the pillow covering my head. To this day I haven’t forgotten the terror on his face when he looked at me. He took me in his arms; I was still bawling and stepped it up when we passed the mirror and I managed to see my swollen brow, bruised forehead and scraped-up face.

“He hit me!” I shouted. “He pushed me, Dad, and rubbed my face into the ground.”

I shouted even louder when I saw my stunned grandfather having to support himself on the chair behind him. “He hit me, Dad. It’s hurting, Dad. Oh, Dad, it hurts, it hurts.”

The Nude Maja by Francisco Goya (detail), 1795–80. Museo del Prado, Madrid

Amid the confusion, my mom gripped my dad by the arm and they took me to get bandaged up. As we were leaving for the hospital, I could see my grandfather looking at me with a brutalised expression, shaking his head. I think I saw a tear run down his sunken face.

After that morning, my parents no longer spoke to my grandfather, who hardly left his room except to use the bathroom. Or to sit and have his snuff in the backyard.

A week went by and I heard my parents talking about him. That same day, a Thursday, I invited my grandfather to play. My aunt, who now stayed at the house while my parents went to work, said to him: “See, Dad? The kid wants to play. You see?”

He nodded. He went to his room, got a piece of cardboard and brought it to the kitchen, a pencil and ruler in his other hand. He sat and stared at the table, daunted, looking up as I took a seat, following my moves, my gaze at the pot of beans I was setting on the table alongside the grid I’d already etched into wood.

I looked at him, tossing my head so the game could begin. He set the cardboard, pencil and ruler on the floor. He ran the tips of his fingers over the grid I’d made, pressing the indentations. He lifted his hand over the pot, took out a few beans, put them into his other hand and placed one on the carved wood of the board. We began the game of one trying to capture the other.

I realised that he wasn’t making any effort to win. But I paid no mind to that; with a few moves, I could have him between my pieces, my nuts surrounding his. I placed the last of them with a solemn gesture. And said softly: “I won.”

When I saw his stony look, I almost cried. Almost. Touching the final bean I’d placed, I came up to his ear and said once more: “I won.”

That’s when my parents got home and approached the kitchen with a representative from the nursing home where they were going to take the old man – I’d overheard the conversation that morning. I mouthed the words again, silently, pulling away while opening my eyes wider as if to make him understand better just what I was telling him: I won. Slowly, in front of everyone, letting my eyes well up, I clasped my grandfather around the neck, brought my face near, and closing my eyes so a tear fell, with seemingly deep love kissed his defeated face.

Translated from the Portuguese by Kim M. Hastings

Nilton Resende is an adjunct professor of literature at the state university of Alagoas (UNEAL), and co-founder of the Ganymedes theatre company. He is the author of two volumes of poetry (O orvalho e os dias and Ouriço), a short story collection (Diabolô), and a critical edition of Lygia Fagundes Telles’s Antes do baile verde.

Nilton Resende is an adjunct professor of literature at the state university of Alagoas (UNEAL), and co-founder of the Ganymedes theatre company. He is the author of two volumes of poetry (O orvalho e os dias and Ouriço), a short story collection (Diabolô), and a critical edition of Lygia Fagundes Telles’s Antes do baile verde.

trajeslunares.com

@niltonjmresende

Author portrait © Josué Seixas

Kim M. Hastings is a freelance translator and editor based in the US. She lived in São Paulo for several years, studied Brazilian language and literature at Brown University, and holds a PhD in Spanish and Portuguese from Yale. Her translations include Edgard Telles Ribeiro’s award-winning novel His Own Man and short fiction published in more than a dozen print and web magazines including Words Without Borders, Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas, Two Lines, Machado de Assis, and stories by Lúcia Bettencourt, Marcelo Moutinho, Alberto Mussa and Ronaldo Wrobel for Bookanista.