It takes guts to make good art

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“From the table talk of ancient Rome to the painted banquets of Renaissance Italy, Barkan is a brilliant, sensual guide to the pleasures of seeing food and tasting art.” Emily Gowers, author of The Loaded Table

“As for you, the vultures will feast on you!” With these words of visceral triumph (quite literally, since he has just thrust his spear into his fallen opponent’s underbelly), Hector, “preeminent among the war-loving Trojans”, finishes off Patroclus in Book XVI of Homer’s Iliad, but only after the latter had been struck down twice already, first by no other than Phoebus Apollo, then by Panthous’ son Euphorbus, both times not face on but miserably from behind. Like a Victorian big-game hunter, Hector is pressing his foot on Patroclus’ dead body, then kicks him, sending him rolling on the dirty ground. He is wearing Achilles’ helmet, which Apollo has knocked off Patroclus’ head, and made to tumble – for the very first time – into the battlefield’s dusty earth. It is a sign that the Greek hero’s semi-divinity is about to expire, but also a profoundly ironic coup, by means of which Hector and Achilles become inseparable as fictional characters, and especially so in the tragic fatality, fallacy and flawed nature of their shared human condition. It is above all a masterly, chilling, superbly astigmatic prefiguration of Achilles’ own hubris, when he will himself return to active combat to avenge the death of his philos, his cherished friend, by killing Hector with equal viciousness and superbia. In all three cases of a hero dying, Trojan or Achaean (for Homer there are no Others here or anywhere, the human value is always, crucially, and inalienably the same), a particular trope serves to expose savagely and unignorably the bestiality and brutality of war: a man, each time, is reduced to a carcass, to an objectified chunk of spoilable and despoilable flesh, fit only for consumption by dogs and vultures.

Food in Homer plays a tremendous role, at least as great as that of his famous animal similes and metaphors. In the Iliad, food is that precious glimpse of shared community, fragile humanity and all-important civilisation when meals are prepared and partaken during the rare instances of a lull in the fighting, either because a pause has been agreed, or because a significant, tragic contrast of private life and normality is wedged pointedly into the narrative; or it serves metaphorically and metonymically as a shocking reminder of how war devours life, society, cosmic order human and divine. In the Odyssey, food is the quintessential symbol by way of which Homer traces Odysseus’ homeward journey, whose cardinal points are not exotic, exciting adventures, but essential stages of nostos, of a true return to life and society, through de-barbarisation and rehumanisation. From warrior he must become again man, artist, communal member and civic leader, son, father, husband. From Troy to Ithaca, each seemingly fantastical episode is an allegory of the premises (and promises) of the good life, examined through the prism of our engagement with that most vital, often denigrated or pooh-poohed substance of all, food. Lotus eaters, Cyclopes or Laestrygonians, Circe, the Sirens or even the feasting Menelaus and Helen’s potions of oblivion, Odysseus’ belly-driven companions, the suitors gorging themselves on another man’s victuals, they are all (negatively) defined by food. The Phaeacians and their idealised perfect copy of Odysseus’ own symposiastic world, as well as Eumaeus and his rustic food and bare-bones yet hospitable, convivial hut, are Homer’s metaphors for the life worth living, nurturing, savouring.

Click on images to enlarge and view in slideshow

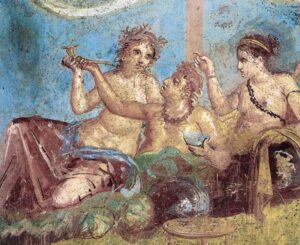

Banquet fresco in the Casa dei Casti Amanti (House of the Chaste Lovers), Pompeii, 1st century AD. Wikimedia Commons

“All stories are stories about food. All interesting stories are directly or indirectly [there] for the food,” according to Leonard Barkan, whose latest sumptuous, eminently absorbing, delectably erudite and cornucopian book The Hungry Eye seeks to trace “a history of culture in which we read for the pleasure of food.” It is a story of journeying and exploring the world for the benefit of food, for the sake of human community, for the sustenance that can be vitally provided by the scrumptiously good and the beautiful. “What is it that puts food in the foreground of our historical community,” from secular art to religious paintings or sacred iconography? For Barkan, it all boils down to one fundamental principle (or sine qua non ingredient): like Erasmus before him, he believes firmly that “God is in the flavour.”

The Hungry Eye is not a history of food but an annalistic encounter with the way food has become a principal interpreter and agent of high art and culture, or of everyday, communal gestures, rituals, practices, private or shared signifiers, the material and the spiritual, in short, the real world that surrounds us in all its hues, manifestations, epiphanies. It is a beautifully personal, resonantly learned, beguilingly written chronicle of how food, throughout the centuries, has brought the via contemplativa and the via activa together. It is about real presence and forced absence or erasure, about the artifice (rather than the art) of centres and margins, about how the material and the spiritual interact, intersect and interjoin. The Hungry Eye is essentially about mystery, and the miraculousness of things in plain sight; it is about individual stories and history, about private acts and traditions – quite centrally, it is about Western traditions and culture. As Barkan declares, “the book is a celebration of the complex forms of debt, with whatever portions of joy and unease, that Western high culture, particularly from antiquity to early modernity, owes to mealtimes… The present volume accepts, even embraces, the archive of the widely known and readily knowable [European] past on the principle that it has been common, available and shared through the millennia.” Its focus is “a fundamental activity that all persons of whatever stratum have had in common: the experience of taste and the gaining of nourishment.”

Barkan is keen to debunk Kant’s arabesque, formalistic and trance-inducing geometrical patterns and schemata in favour of a truly creative celebration of the distinct individuality that unites us as a species.”

In a very real way, The Hungry Eye stresses an engagement with food that is alike to the engagement with a sacred object: both require first a physical encounter through sight, touch and smell (taste being, as Barkan points out, arguably both touch and smell), then a conceptual processing of the encounter: a transcendental one for the sacred object, an equally consummate one for food, whether through sublime transubstantiation, or digestive and emotional gratification. Both food and the divine in Barkan’s book assume (presume) a living presence, and his is, to use the formulation of the late Robert Fagles, a distinctly Helleno-(Romano)-Judaeo-Christian living presence. It is also a vastly movable, immutable, communal feast: “couldn’t we say that the whole humanist project of rebirthing the past is an attempt to counteract loneliness by means of a transhistorical dinner party?”

Refreshingly, Barkan’s book is not a gnoseological compendium or an analytical discourse on food and art, the aesthetic body and the eye of the mind, on dominant or repressed structures, or on high and low power struggles, although all of these become radically incisive prisms (and unconventionally or un-ideologically redefined ones) through which to approach the praxis he is most interested in: that of creating a Warburgian, Mnemosyne-type narrative of our relationship, through food or thought (through food for thought, or thoughts on food), to the real and the sublime. He begins with an analysis of Kant’s Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, a peculiarly counter-intuitive Kantian diatribe, where the oxymoron of deriving and designating “the aesthetic faculty of judging” by way of the consumption of food becomes a litmus test for Kant’s very Sin und Sein. How can the sublime be so organically linked to gustus, sapor, Geschmäck, bon goût, fine taste, the lowly, belching gaster? Kant, Barkan posits, “has recourse to a sort of proto-Darwinian linguistic argument. Sapor… is related to sapientia (wisdom)”, from sapio/sapere, which means both I have (good) taste/I taste good and I have discernment/I know/I understand. “The human species, it turns out, possesses a sense – taste – that instinctively identifies that which is wholesome, and repels that which is noxious.” That Kant has to wriggle (“squirm”) his way from the material and tangible, the corporeal and sensual, to the conceptually ideal and universal, is quite a treat for Barkan (and undoubtedly for many others, too).

Barkan is keen to debunk Kant’s arabesque, formalistic and trance-inducing geometrical patterns and schemata in favour of a truly creative celebration of the distinct individuality that unites us as a species, as a dynamic plexus of cultures and civilising traditions. His engagement with Plato’s Symposium provides the guiding principle he will follow throughout this book, namely the transubstantiation of our intellectual, aesthetic and spiritual understanding of ourselves through the process (and the culture) of food and drink: “the spiritual [is emphatically] reconnected to the physical”, from Aristophanes’ philosophical (as well as material) hiccups and borborygms, to Alcibiades’ inspired (or intoxicated) disputation on the physical experience rather than the abstract Platonic idea of Eros. It is an ingenious act of communion between dialectics and Aristotelian methexis, that aligns itself with Ernst Cassirer’s theories on the power of words and images to express the ineffable, to create symbolic systems through art, myth, social rituals, language, techne, by way of which we understand our own reality but also our relatedness to others and to the world; it is indebted to Fritz Saxl’s notion of “classic images”, that become dynamic and transformative cultural archetypes across time, and to Erwin Panofsky’s “human mind”, and it is crucially dependent upon an art-historical, comparative and interdisciplinary cultural approach; it owes much to the whisperings of many Diotimas, and is engaged in a continuous, maieutic discourse with Socrates – and his manifold wisdom, and multiple contradictions. The visceral side of beauty for Barkan is a way of approaching “the human sensorium” in order to grasp the very process of human understanding, perception, interpretation. After Paul Ricoeur, he seeks to recapture the heuristic interplay between the mind and the senses, that creative agency that has made our world, by tracing the gestures, in food and art, of “man the hermeneutical animal.”

Madonna and Child by Carlo Crivelli, c. 1490. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

The Roman army marched on its stomach, or as Barkan puts it, “Athens philosophises; Florence paints; Rome eats.” Romanitas, Food and Culture are triangulated in the first section of The Hungry Eye, which proposes no less than a foundation narrative for later European civilisations. Foundation narratives are crucial for Barkan, and they were certainly so for the ancient Europeans. The most enduring and catalytic Roman ones, that of Romulus and Remus, and Virgil’s Aeneid, both depend upon particular engagements with food: in the first, siblings who have been nurtured by the same she-wolf fight a deadly duel for the power to rule; in the second, a new patria is designated as the spot where one eats not only one’s food but one’s plate as well. It is, one could argue, a complex case of bonum et utile, twisted and revised to suit one’s purpose, whereas for the Greeks, or at least the Athenians, it is more a question of that Homeric (again) ὁλίγον τε φίλον τε, that mere nothing that one loves – also known as τό μικρόν τό μέγα, that small, unnecessary thing that contains all of life’s worth and greatness. In their own creation story, they pit Athena and Poseidon vying to name the newly founded city: Poseidon promises power in the form of land armies (horse) or in an alternative version naval forces (sea water); Athena offers invariably a scrawny olive tree, namely peace and a (relatively) frugal life. Given how much the Romans looked back (or over their shoulder) to the Greeks, a comparison of paradigms here certainly gives much to mull over and think about, especially since the habit of “Latin back-formation”, i.e. of assigning traditions distinct to themselves back to the Greeks in order to anachronically ratify and ‘appropriate’ them, tells us much “about the story that Romans wanted to tell themselves.” From “banqueting practices” and cultural scenographies to political theorising and philosophical musings, each is a case of “aggressively adopted Greek”, or of eating not only one’s food but the cultural plate on which it had been first served, and which now becomes “publicly claimable” heritage – a gesture still in vogue today, and across time.

The metaphorics of food and drink served to forge a sense of cultural superiority, as well as an awareness of identity, they establish indigeneity and alterity, enforce ‘reception’ and the right to a ‘same but other’ self-definition.”

“In the chronicles that Romans produced about their own past, the account of what they ate and how those edibles were produced plays a significant role.” Food and drink become the means to conquer, the words to say it, the metaphorics to think, live and die by. They are signifiers of refinement and aesthetic culture, agonistically defined and appropriated, tokens of mastery over nature in the way Romans developed sophisticated modes of cultivation and production, proof of command over knowledge through near-obsessive encyclopedism, and the very real insignia of dominion over the oikumene, by virtue of their being able to place on their tables exotic, rarefied products from the lands they had conquered. It is a highly complex, literally spectacular system of values, gestures, edifices of statecraft and cultural modes, where panem et circenses was essentially panem et potestas. The metaphorics of food and drink served to forge a sense of cultural superiority, as well as an awareness of identity, they establish indigeneity and alterity, enforce “reception” and the right to a “same but other” self-definition, as well as evincing, on the other hand, an extraordinary ability to be curious about worlds and people beyond one’s experience or even understanding. To engage in polyphony and multiculturalism, to wonder about the cosmos, the here and the afterlife: “Romans… can be made to understand cultural implications with remarkable force if the tropes of description are culinary.”

The Chamber of Cupid and Psyche by Giulio Romano, 1527, Palazzo Te, Mantua

Barkan’s second Mnemosyne territory is biblical textuality and gastronomy, through Jewish and Christian eyes. Here the aim is to put physical aesthesis firmly back into aesthetics and, as with Rome, the interaction between word, food practice and praxis, and representation in art or cultural gesture is as breathtaking as it is mesmeric. How does one read food in Biblical and Christological iconography? Especially when representation itself of both the sacred and the real was often placed under suspicion? Barkan tackles head on the question of “privileging the sign in place of the signified”, the complexities of reading, seeing, existing both literally and materially, as well as through parable and symbolism, the indescribable that is both ineffable and an undeniably solid, humanly incarnated Word. Commensality and eucharist, the question of ‘what is’, both in ontological terms (Manna as food) and eschatological ones (God), the relationship between the I and the Thou through both presence and absence, the hermeneutics of words that reveal as much as they trouble or confuse, signpost a thrilling journey through two millennia of drinking, eating, and doubting or believing. “In the Hebrew Bible food was the meeting point between God and man, but it is a meeting point only in a conceptual sense: God’s manna and kitchen manna may be the same substance, but they exist in a state of opposition. Once Jesus is the bread that comes from heaven, the definitively human act of consuming food turns out to define God as well.”

Yet the relationship of visualising that “as wellness” is not a simple one. From the tricky word “pinax” in the story of St John the Baptist and Salome (is it a food platter, a writing tabula, a Homeric meat slab, as Eustathius tells us, or the self-portrait of the truly virtuous life, as in the tabula of Cebes? An ironic votive tablet on Salome’s part?), “to represent what cannot be represented is truly high art”, as well as the ultimate, gutsy enunciation of the “Al divino dall’umano. All’etterno dal tempo” principle, namely of incarnation, even when this is taken to extremes, as in Pieter Aertsen’s Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt (1551), or his Vanitas, Still Life with Jesus, Mary and Martha (1552). The story of “fooding the Bible… has been overwhelmingly about narrative,” says Barkan of his own approach to it, claiming to have “much less to say about sacred symbolism.” This may or may not be true. He certainly does not offer a doxological (or Meyendorff-style) analysis of a sacred art-historical technique and language, yet follow his lead into pictures and the stories they try to tell, and what you will find is one of the most sensitive, illuminating, and devoted (rather than devotional) engagements with the questions and answers, real and hermeneutical, involved in the Judaeo-Christian quest for the divine, in the dialectics between life and afterlife, the act of living and the space for understanding. Namely, the juncture between the physical and the metaphysical.

Detail from the West face, Chamber of Cupid and Psyche, Palazzo Te

How we speak about things that perplex us, or things that are so fundamental that to call them self-evident is to quite miss the point, is the next vast yet vital aporia for Barkan, always, of course, centred around food. Socrates pops back on the stage, this time engaged with his photographic negative, the sophist Gorgias. A tiny word, “ἑορτή”, which can translate as feast, celebration, festival, amusement or pastime, gives rise to an inspired discourse on the distinction between rhetoric (Gorgias’ sophistic techne) and dialectics (Socrates’ art of reasoning). For Barkan, this is no simple dichotomy between good and evil, truth and deception, but a deeply textured hermeneutics involving materiality and abstraction – in short, food and the living of life, and intellection. Gorgias’ sophistry is a celebration of alchemic proportions, an intangible transformation of ingredients into a consummate (and supremely spellbinding) concoction which we digest, Socrates implies, without becoming aware of its more unsavoury elements and secret additives. It is like cooking, both intuitive and perfected through experiential practice. Dialectics, on the other hand, have clarity, order, transparency. Sophistry, like cooking, is for Socrates “an activity of mere sensuous gratifications rather than the sort of oratory that would lead to proper action in the public sphere.”

The concern for Socrates is the lure of pleasure. Sophistry beguiles, tricks the palate (or in this case the mind) into consuming without either critical appreciation or true understanding. By comparison, philosophy runs the risk of being deemed bland (or even unsavoury or difficult to digest), and thus loses out in the race for educating (or tantalising) the public mind. The cultural background for Socrates’ mistrust of unreflected indulgence in the pleasurable is critical. For Athenians, excessive lucre, ostentation, preciosity, gourmand eating are associated with satrapy, oriental autocracy, hubris and narcissistic self-love. In Periclean Athens the debate on what counted as civilising art and culture, and what was quite simply a self-enslavement to vain and conceited materialism, was a heated one. And as Thucydides’ version of Pericles’ Funerary Oration shows, it lay at the very heart of what the city wanted to be, or at least to seem to be, as a cultural paradigm and civic power. Gorgias’ consumerist approach, to both words and thoughts, and to food or way of life, was bound to irk Socrates, for whom a self-effacing metron and reflection were everything.

The Hungry Eye is a book capable of marking its readers, of changing their lives… a feast for the eyes and for the mind, a truly restorative engagement with everything we are, the traditions, history and cultural gestures that have shaped us.”

The Feast of Herod by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1533. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

By the time of another Greek, also a rhetorician and philosopher, living in Egypt during Roman times, the balance of the scales had shifted ever so slightly. Athenaeus, whose Deipnosophistae (loosely translated as The Annals of the Philosophers’ Dining Club) is one of the most extraordinary treasure-troves of ancient lore, texts and vibrant scenes from everyday life, would set out to show that “food and wine may or may not belong at the table with high culture, but curious things happen when they are admitted there.” No longer under the sign of the very real Persian menace (both in terms of military aggression and of cultural alienation), Athenaeus refutes in his own symposium the Socratic angst regarding pleasure by placing it at the very heart of the pursuit of goodness and wisdom. From Athenaeus to Rabelais is a mighty leap, but a predictable one. Another European crisis creates yet more cultural discomfort, and the sarcastic, iconoclastic parody Gargantua and Pantagruel is a sign of its times. This is the Renaissance tweaked by the Reformation, an age of acute contradictions as well as sweeping and polarising affirmations and refutations, the precursor (or pasta madre) of Le Siècle des Lumières, and the Age of Reason. More positively, it is a moment when human individuality seeks to retain its relation with the godly, but also stand up to it if not in defiance, then at least in some sort of more equitable, dialectical relationship. Such a new iconicity of the self also inevitably “transforms the subject of love [of the Platonic Symposium, as well as the agape of Christianity] into that of self-love… understood in the crassest terms.” Rabelais’ word for this is philautic, i.e. an obsession with self-referentiality, and an equally disruptive reading would be to argue that an anachronically parallel text here is Voltaire’s Candide and the covalent crassness of Dr Pangloss’ dictatorship of monolithic logic. A society worshiping either a material or systematising pragmatism forgets the simpler (deeper) wisdom of the Socratic daimonion. It is a crisis that is spiritual as well as existential, and a counter-voice comes from Rabelais’ friend Joachim du Bellay and his famous poem on the Odyssean happiness of finally enjoying the hearth of one’s home (and one imagines the food cooked therein) after one’s long travels and travails…

Butcher’s Stall with the Flight into Egypt by Pieter Aertsen, 1551. Uppsala University Art Collections – Gustavianum/Wikimedia Commons

The Gargantuan cosmology, ethology and philosophy are utopian par excellence, and ab initio: they are the first French example of the principle of a non-place of existence, of a self-destructive and autoclastic humanity, or of what for Rabelais were the over-prescriptive analytics of Aristotelianism (and its Christian offspring, scholasticism). Yet what of culinary prescriptions, otherwise known as recipes? You will have to read Barkan’s radical reading (and feisty rehabilitation) of Bartolomeo Sacchi’s De Honesta Voluptate et Valetudine (On Honourable Pleasure and Well-Being), to find out. Il Platina’s manual on food (the first ever modern cookbook) was a “terrifying little book” that caused immense trouble for individuals and history alike. Barkan ventures on a ferocious autopsy of Renaissance society and politics, involving no less than a plot to murder a Pope, which might (or might not?) have involved Mohammed II. Suffice it to say that, as ever in this book, the game is afoot, and you would be unwise not to follow apace.

The Renaissance is not only Botticelli and Michelangelo, Raphael and Bronzino, Bellini and Francesco Salviati, Hieronymus Bosch or El Greco. It also includes literally colossal extravaganzas such as the frescoes of Mantua’s Palazzo del Te, and if you have ever found yourselves perplexed, bemused with incredulity, or overwhelmed by the non-Hellenic or even Roman corpulence, and the cryptically improvisational allegorics of its Hercules-themed, gigantic tableaux looming above and around you, Barkan’s analysis will direct your eye, soothe your aesthetic sensibilities, and quite genuinely bring you back to your senses, so that you may decipher, or meta-read, this extraordinary hyperbolic spectacle, by transporting you from (parochial and Gargantuan) Mantua to (sophisticated and Titanic) Rome and the corresponding frescoes of the Villa Farnesina. Barkan will initiate you to the “terrible realism” of both, moving onwards to Boccacio, Bruegel the Elder, Columbus and the Americas, William Strachey and Shakespeare’s The Tempest, in what is a magisterial analysis of modernity’s new foundation myth of the noble savage and his own cornucopian utopia.

Still Life with a Turkey Pie by Pieter Claesz, 1627. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

“Eating and drinking… seem to have often entered high culture via a denial, or a sublimation, of eating and drinking.” In many cases, this denial and sublimation were as fraught with Freudian complexes as any, in others they would create the space for a particularly polysemous and empowering relationship between symbol and material actuality. According to Vitruvius, the ancient Greeks would include frescoed pantries and dining corners as part of the spaces reserved for guests. These food themed frescoes were called xenia, or welcomings, they were the visual, heavily signified tokens of hospitality. By way of conclusion, Barkan will consider the dynamics of such and all “still lives” and the vividness of “natures mortes”, the transcendental depths of the mere Ding an Sich. It is a fitting culmination of a formidable, panoptical itinerary across European spaces and topoi, through image, real presence and iconicity. Above all, through a particularly palpable, sensuous, multi-sensory and synaesthetic encounter with food and drink as fundamental nourishment and as what nurtures the very meaning of both individual and cultural survival. Barkan’s last supper, so to speak, will involve Francis Bacon, Marcel Proust, Milton and the Genesis story of Adam and Eve, as well as the metaphorics of memory, of real existence, of sacred or “mere mortal” transubstantiation. It is a eucharistic as well as cathartic way to not quite finish, but rather to proclaim that nunc est bibendum, perhaps echoing Horace’s own triumphant undertones, as well as the subtextual reference to the Roman defeat at the Battle of Drepana during the First Punic War. There, the general responsible for the debacle, Publius Claudius Pulcher, majestically threw the sacred oracular fowl overboard with the famous words: bibant, quoniam esse nollent – let them drink, since they refuse to eat. Horace’s invitation to raise a glass of wine came from what was seen as the revanche coup for Rome, namely the Battle of Actium, where portent and victory happily converged…

The Hungry Eye is a book that is capable of marking its readers, of changing their lives. It is certainly a feast for the eyes and for the mind, a truly restorative engagement with everything we are, the traditions, history and cultural gestures that have shaped us, informed us, challenged us to reflect about what matters. We have learned to think audaciously, creatively, inspiredly and critically, to create beauty, and to live a life finely balanced across both mind and body thanks to this palimpsest called Western civilisation, and Barkan has all the guts it takes to reveal the beauty and wisdom of that tradition, its inalienable meaningfulness, dialecticity, inclusivity and deeply human journey of goodness and wisdom, as well as its Scyllas and Charybdis. If you yearn for an unmissable, learned as well as exceptionally warm, convivial and lively conversation over a glass of something and a nibble of something else, on that unforgettable line by Menander, “Ὡς χαρίεν ἔστ’ ἄνθρωπος, ἄν ἄνθρωπος ᾖ” (What a perfect thing is man, when he is worthy of his own humanity), then The Hungry Eye will be for you both an invitation and an initiation to a feast of culture and life…

Leonard Barkan is the Class of 1943 University Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University. His books include Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures (Princeton University Press, 2011), Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture, and Satyr Square: A Year, a Life in Rome. The Hungry Eye (September, 2021) is published in hardback and eBook by Princeton University Press.

Leonard Barkan is the Class of 1943 University Professor of Comparative Literature at Princeton University. His books include Mute Poetry, Speaking Pictures (Princeton University Press, 2011), Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture, and Satyr Square: A Year, a Life in Rome. The Hungry Eye (September, 2021) is published in hardback and eBook by Princeton University Press.

Read more

complit.princeton.edu

@LeonardBarkan

@PrincetonUPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/