Trees need cuddles too

by Kate Worsley

5pm, Monday: “The permission has come through. Can we come and do it tomorrow, first thing?”

During the pandemic, I’d sit out in the shade of the 150-year-old copper beech that dominates – defines – my back garden, and feel luckier than most, for the first time in years.

I’ve never been a gardener, or indeed able to grow anything much at all; I don’t know the names of anything, let alone the Latin versions. I’m a lawn sprawler and at-times-compulsive hacker-backer, not a tender and coaxer. And after almost a decade of solo parenting and breadwinning, I’d managed to give up on compulsive anything and was in full-on goblin mode: I’d given up on clearing the dead wood. I’d let the lawn go wild and we had huge daisies and the hedgehog was back.

On 26 September 2021, a pretty, golden-brown striped and frilly fungus appears at the base of the beech tree, a lacey posey of a neckerchief.

Yikes, I post a pic. Autumn has arrived chez moi.

Brilliant! replies Chloe. Like pancakes and parsley.

7:30am, Tuesday: Before work, I unlock the back gate, put away the washing line. I make them a tray of tea, with sugar and biscuits. I can hear them unloading the truck.

On 7 September 2022 the pretty fungus reappears.

Pancakes and parsley for Chloe, I post.

Five days later there are five bouquets of the stuff.

Getting a bit freaked out now.

A fortnight later the bouquets have merged, grown heavy and fleshy, pungent, are gathering about the base of the tree. My middle son asks me to send him more pics, and gives it a name. I don’t bother to look it up.

There has been so much I have been unable to foresee or prevent, to restore or save. Everyone else has moved on, moved out. Now it’s just me and my youngest. And that tree, that I thought would outlast us too.”

One morning I sit down to work and when I glance out the window the fungus has risen up, like a foaming murky yellow tidal wave, engulfing the roots. It emits a hazy cloud of spores that drifts like smoke from a smouldering bonfire and seems to whitewash the trunk. I google the name my son gave me.

10am: Somehow the cherry picker is through the gate, a small caravan unfolded on the lawn. As I take out another pot of tea I glimpse a hi-vis jacket halfway up the tree. I’m glad I’m Zooming all day. I won’t look.

It was the tree that had sold me on the house, a very ordinary house, the minute I walked through the side gate, heavily pregnant. The novel thrill of its massive, stockinged, varicose green-grey trunk and dizzying, up-reaching intricate branches, with their promise of shade, privacy and shelter. Our first garden. Our first tree. One morning tiny shell-pink leaves appeared, then burnished to copper, eventually turned a greenish iron dark. The baby gurgled as next-door’s girls came over to shriek and jump in their huge raked piles.

It was so huge neighbours worried about subsidence, so I found tree surgeons to keep it in check, a father-and-daughter team who moved like panthers through its canopy. Beech branches drop without warning, so we never hung the long swing I’d dreamt of. But I had Marimekko curtains made up to mirror its branches so we could see its shadow, even at night.

We all came to take it for granted. A pillar of family life, it stood sentinel 24/7. Through the best of times, and then the worst.

I go out to check. But I can’t bring myself to touch it. It’s rich, loamy-mushroomy scent now smells rank to me. I message the tree surgeons.

Josie calls straight back. Says her dad will be over.

12:30pm: After I have lunch, I make a fresh pot and take it out.

This is when I burst into tears.

It’s ridiculous. A proper crying jag. I wander round the house with my hands over my mouth. Why am I sobbing?

The prospect of losing this tree feels unbearable. It’s illogical, surely. Isn’t the fungus just as important in the bio-diverse scheme of things?

Gradually, I realise how familiar this tightness in my chest is, the uncontrollable leaking of tears, this vertiginous, nauseating grief. Because we have lost so much since moving to Beech House. There has been so much grief here. And apart from anything else I have loved that tree because its leaves have meant the people in the flats can’t see me crying as I hang out a wash.

There has been so much I have been unable to foresee or prevent, to restore or save. Everyone else has moved on, moved out. Now it’s just me and my youngest. And that tree, that I thought would outlast us too.

I don’t post. I go out in the early morning with my coffee and lay my hand on its cool flank. Who can you tell that you are eating your heart out over a tree? A cat, a dog even, but a tree? How scornful I’d been of the sentiments in overly reverential nature writing. I’d never felt it in my gut like this. The primal conservatism of love.

A tree becomes more vulnerable as it ages. But it can and will resist, it will fight back, and I can help it.”

It’s the council tree officer who comes. He is solemn. The beech may well have to go. Felling it could cost thousands. No, I wouldn’t be able to claim it on insurance. No, I couldn’t have foreseen that pretty growth was such an insidious threat, or prevented it. And no, now it’s here, it’s here.

My new partner finds the spades and we spend the weekend digging it all up, every scrap. We lug it, in ten heavy bags, to the tip. I for one may never eat mushrooms again.

By 4 November, when an arboricultural consultant nails his fairy ring of glowing green and blue sensors around my beech, I think I have accustomed myself to its loss.

A tree becomes more vulnerable as it ages. I nod sadly. But then what he tells me is that it can and will resist, it will fight back, and I can help it. I can do my best for it and look after it, the way I feel – ridiculous as it sounds – that it has looked after me. If we reduce the canopy – hard – it can concentrate its resources in its roots and overwhelm the fungus. Cling on. Self-optimise.

2:30pm: I take a break from work and go for a walk. On the way back, I see the crown of the beech freshly shorn but not diminished, still just visible over my roof. Still there, still tall. I take out another pot. They are all done. Just two small piles of logs on the lawn.

Yes, says Josie, I know. When we looked at the report he’d marked to only go back to where we first lopped it, when you moved in, remember?

We’ll test again in two or three years’ time, says Dom. He sees my face. He understands. Don’t worry. We can rely on the tree to do its job.

4pm: Final pot. I sit down with them, father and daughter, before they go back to restart their own endless cycle of work: unload, clean, mend, sharpen, reload. Can’t remember the last time I saw the inside of a pub.

I want to hug that tree, I tell my youngest when he gets home from school.

Cute, he says. Trees need cuddles too. It’s had a tough time, hasn’t it?

I don’t, of course. Too British.

—

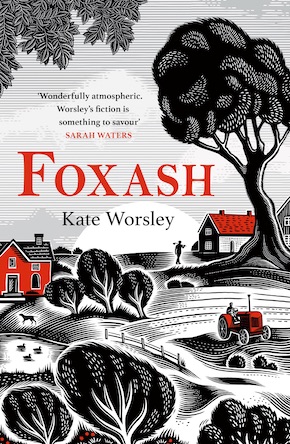

Kate Worsley’s first novel, She Rises, won the HWA Debut Crown for Historical Fiction and was shortlisted for a Lambda Literary Prize in the US. She was born in Lancashire and now lives on the Essex coast. Her latest novel Foxash is published by Tinder Press in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

Instagram: worsleywrite

@TinderPress

Author photo by Rick Pushinksy

Fungus and copper beech courtesy of the author