Truth in sculpture

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A total delight. It brings to life the relationship between a genius and his patron, and with an ease of writing that is rare in art history.” Simon Jenkins

Sometime between the 4th and the 3rd century BC, Poseidippus of Pella wrote the following epigram on the art of breathing life into stone, as he describes the statue of the poet Philitas of Cos by Hekataion:

He fashioned the elderly pedant using all his craft,

and in accordance with the proper rule of truth.

Indeed, he looks as though he were about to speak,

endowed with such a vivid personality,

for all that the old man is made of bronze.

By order of Ptolemy, both god and king,

the man from Kos now owes his new life to the Muses.

In many ways, this is a near-perfect definition of Hellenistic art – its mastery of the human form, its canon of the human rather than the heroic, its extraordinary insight into the human psyche, which is translated into a practice and an ethics of representation. Especially its idealising principles, its convictions regarding the aesthetic potential of realism, the “beauty of truth” as Gianfranco Adornato calls it, which it combines vitally, swooningly, with its unwavering emphasis on the merely human, that radical new perspective that marked so profoundly every aspect of Hellenistic art and life. A glimpse of the Hanging Marsyas, from Maecenas’ Auditorium, a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original now in the Musei Capitolini in Rome, or the Old Woman, again a Roman copy of a 3rd or 2nd century Hellenistic original, currently in the British Museum, the Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, the Terme Boxer in the National Museum of Rome, the Athena Medallion in the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, or the Portrait of a Philosopher and the famous Horse and Jockey from Artemision, both in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, will transport you to a throbbing, living world, filled with the most intense emotions, and the greatest diversity of possibilities, human experiences, life stories. A world where pathos is coupled with a new perspective regarding both human form and human fate; where the economy and the iconography of the mundane and the ordinary exist alongside the structures of image-making and of power. Fast-forward to the 17th century AD, and that same epigram might just as well have been written about Gian Lorenzo Bernini, one of the most enigmatic and supremely talented Great Masters of Baroque art. He was architect, sculptor, painter and draughtsman, master of ceremonies when spectacular displays and fanfares were required, a prolific writer of masques and burlesques, and especially a remarkably shrewd entrepreneur, who managed not only to survive but to thrive during the office of no fewer than ten popes.

Grossman’s Bernini is more than an art-historical subject: he is the exemplum through which to examine the ‘shocking’ revolution brought about by Baroque art, and the new ideas that produced it.”

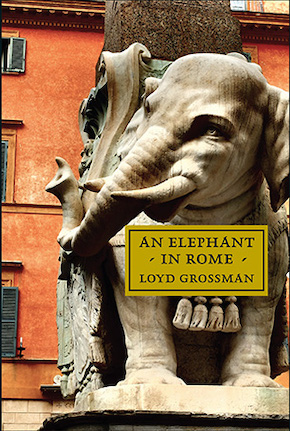

Bernini is the subject of Loyd Grossman’s exuberant, engrossing, and flamboyant new book, An Elephant in Rome, where he sets out to show how Bernini transformed in many ways the expectations and the ambitions of European sculpture: even at their most grandly monumental, his works “still mesmerise with the beauty and skill of their carving, the boldness of their conception and their sheer energy,” as Grossman writes, and bear unmistakable witness to the “miracles Bernini performs in making marbles speak” in the words of the poet Lelio Guidiccioni. Grossman’s Bernini is more than an art-historical subject: he is the exemplum through which to examine the ‘shocking’ revolution brought about by Baroque art, and the new ideas that produced it (“the Baroque is when you can draw a straight line but choose instead to draw a curve; the Baroque is when you are bored with the melody and wish to listen to the variations,” in the words of Luigi Barzini). He is also emblematic of the last man standing in a world now devastated by crises – geopolitical, ideological, religious, social. For Grossman, that misshapen, uncategorisable pearl of a period is the perfect miniature through which to explore the triumphs and the failings of our own insignificance and greatness. An Elephant in Rome makes full and rather spectacular use of that most baroque of art terms, the concetto, “the ingenious thought that gave birth to a work of art” – the idea that a work of art is the vehicle of a conscious and deliberate intellectual concept or narrative, or, in Grossman’s case, a distinct politicised programme. In his hands, Bernini’s unforgettable elephant and the obelisk on his back become more than a point of focus, or the excursus for a longer story that aches to be told: they are finely calibrated, precise instruments of enquiry and meaning.

Grossman plunges right into things – proving his point that Rome is not a site, but rather the urban stage of an intensely personal, formidably historical, and unpredictably marvellous experience. You will stumble upon stiffs, or “such stuff as dreams are made on”, in almost equal measure, and you will come somewhat close to succumbing to Stendhal’s syndrome, yet worry not, for this is Rome, not Florence (the syndrome’s alma mater), so you should easily recover. Grossman has a talent for combining quick-witted, live commentary (he walks with you across Rome, and he will walk you through every grand monument and unsuspected ordinary wonder), with meticulously researched historical and art-historical analysis. He will sweep you off your feet, should you let him, and you would be rather a fool not to.

This is a densely rich book, an abundance of views and visions. Culture here is as much life (Roman or not) as is breathing, and the relish of curious, intelligent thinking is tantamount to a life worth living. Grossman reads landscapes, monuments and buildings, the lives of major and minor figures whose mortal remains have long turned to dust, with a sharp (sometimes unsparing) eye for social commentary, for literary, historical, philosophical connections between past and present. He shows us Rome as a heaving, constantly metamorphosing organism, as an extraordinary state of being and becoming. Every stone or page he picks up for scrutiny and display has a story to tell, the many stories linked by the golden thread of a continuous human spirit and presence, an ever-evolving cultural essence.

The Elephant of the Piazza della Minerva steps gingerly through great roads and alleys, sometimes basking in the blazing sun, at others hiding in the cooling shadows. He is always swishing his semantically over-charged tail, with Grossman perhaps imagining himself swaying intoxicatingly on his back, majestic and maharaja-like. He will maintain this lofty perspective throughout, leading us through a luscious landscape of rather murky history, not altogether spotless politics, the dynamic presence, evolution and complicity of art, and the emerging individuality and market power of artists. Grossman can be magisterial (he has an MA and DPhil in the History of Art, a long personal involvement in art patronage, and a rich family history in antique dealing and collecting), an irreverent maverick (he has played in several punk bands as a guitarist, as well as writing The Social History of Rock Music), and a smart showman (he is widely recognisable for his numerous TV shows, let alone his ubiquitous tomato sauces…) An Elephant in Rome is a sublime product of the best qualities of his disparate life experiences and skills, erudite and highly enjoyable in turn, extravagantly staged and intellectually stimulating in one go.

Grossman is an enthusiastic pilgrim to Rome’s art, and a keen admirer of Bernini, even though the distance in doxological and perhaps cultural perspectives occasionally seems to present difficulties of notional attachment and of intellectual approximation. Christianity as reflected in religious sculpture is a point in question, as Grossman sometimes finds it “sickly and unconvincing” as he writes of Bernini’s St Bibiana, as are devotional architecture, the place of religion in European history and society, the particular nuances and substantial dynamics of geopolitics. Overall, the social environment, the political framework as seen by a particular school of historical interpretation and the structures of power, as well as the key role of economics and the leverage mechanisms of self-branding and market placement, are as important in Grossman’s view of things as are his insights into aesthetics, artistic production, the vast cultural project that was Bernini’s time. In Grossman’s model, they are all tightly intertwined and interdependent, revolving ineluctably and unswervingly around the papacy and its struggles for power: the Popes “understood the power of great art as spin and propaganda,” Grossman affirms variously (and somewhat repetitiously) throughout, and he bolsters this conviction with intensely focused readings of micro or macro episodes of the time, from the Great Schism (not the 1054 one, but the one in 1378, between France and Italy), to the Council of Trent, the Peace of Westphalia, and Pope Alexander VII’s efforts to emulate the other Greats, Augustus and Alexander, as well as lead the simple and contemplative life of an ordinary pope, while fighting (very successfully) his very own pandemic.

Art not only painted a picture of the world as it was or as it ought to be, it above all conjured that world, sometimes out of thin air.”

Bernini’s life is marked by an almost inordinate number of turning points – not only his, but more crucially for the Papal States and the status and statutes of the Catholic Church, for European politics, for social balances. Grossman is unquestionably a fascinating observer of that life, and of the many lives beyond it and around it, and perhaps the intensely personal, singularly instinctive character of Bernini’s art that he perceives was a response to such new challenges and opportunities, to the pressing need to redefine individual existence, will and expression; to rearticulate the role and purpose of art, reclaim its audience, and re-kickstart its dynamic evolution into an agent of radical new meanings and balances; to confront new crises and old dilemmas. Art not only painted a picture of the world as it was or as it ought to be, it above all conjured that world, sometimes out of thin air, it projected desired iconographies or ideological constructs in a powerfully influential and persuasive manner, and it subtly revised nonconformist representations. Its mesmerising power of images was also a political and doxological gesture against the Reformation’s anti-iconic revolt. It is a highly energised, perceptive reading that Grossman is eager to propagate, flesh out, and animate with particularly evocative skill. He is strong on facts, vocal on ideas, pugnacious on interpretative convictions and angles of exegesis.

The symbolism of social engineering and mobility is particularly resonant in Grossman’s account, laying emphasis on the little-stressed fact that the privileged have always been underprivileged at some point or another: he recounts the story of the Barberini family, which counted Pope Urban VIII among its members, and which was renowned for its wealth, lust for power and ambition. Having begun the genealogical cursus honorum as a “successful dynasty of tailors”, whose original name was Tafani da Barberino, they changed their emblem, three tafani or horseflies, to “the altogether more appropriate bees, symbols of industry, social order and hierarchy, ideal for a family that reached for and won the papacy.” There are swarms of Barberini bees (and undoubtedly a few horseflies) in Rome, together with a vacancy, Grossman says, for “an ambitions PhD student” who may want to count them all.

Grossman places great symbolic power on cultural typographies, such as the Italian fixation with fare bella figura socially or literally, and on methodologies of historical materialism. He likes to debunk received knowledge or authority with the same vigour he ascribes to Pope Sixtus, and this latter’s bold demolition of past structures, his claiming of them as spolia for the erection of his own grand(er) monuments. He is dialectical enough for the process to be a stimulating one, but the rather totalising nature of his premise can sometimes tire, and also expose the few failings in his narrative, namely a selectivity in his perspective that leaves many questions unanswered or simply ignored outright; an overall dismissal of the more complex and human, less dogmatising and tokenising canvas and historical reality; and an authorial slant that claims as much ‘patriarchy’ in its vehemence as the systems he denounces. In his efforts towards an absolute objectivity, Grossman sometimes falls prey to what Nicolai Berdyaev termed “objectification”, the reductionist process of a rigid ideological detachment that dehumanises and de-substantiates its subject.

Another sad omission has to do with art history itself. The immense influence of Hellenistic art on Renaissance and Baroque artists, often through the mediation of Byzantium, is not explored, and it is a pity that we do not get a more vivid, broader, more fleshed out and populated landscape of the artists who picked up the trail where Michelangelo, Raphael and Donatello had left off, which is inevitably the beginning of Bernini’s own enthralling peregrinations. There is the more unwieldly Baccio Bandineli (who left his own mark in Santa Maria sopra Minerva) and his emphasis on the body and on mortality, rather than on the spirit and transcendence; or Benvenuto Cellini and his redefinition of the School of Fontainebleau’s elongated, sensuous, perfectly poised, almost suspended forms, his skill in capturing the breaking tension of the irrational and the terrible, as in his portrait of Cosimo I dei Medici and his Perseus, which is clearly referenced in Bernini’s David. With Perseus, Cellini shifted the very relationship between art and life: Wilde-like, he radically turned the tables, causing “art [to] become the archetype of Nature”. Vincenzo Danti would take this sense of terribilita to an entirely different level in his Honour Triumphant over Falsehood. His is an uncanny physicality, that the Baroque would embrace with not insignificant thrill, especially through the mediation of Giovanni Bologna (Giambologna), as in his Rape of the Sabine Women. His Turkey has interesting comic similarities to Bernini’s Elephant, and he is one of the key bridges with Hellenistic and Classical Greek art and culture, so crucial to the understanding of Bernini’s own development. Della Porta, whose tomb for Pope Paul III Bernini modified as a pendant to his own tomb for Pope Urban VIII, Sansovino’s reflective, dynamically psychological style, Vittoria’s highly realist portraiture, even within the strict decorum of his age, or Tiziano Aspetti, in some ways Bernini’s alter ego, are all notable absences from Grossman’s admittedly cornucopian story.

Elephant and Obelisk is not mentioned by Bernini’s two contemporary biographers, yet Grossman is riveting in his analysis of the evolution of the ideas involved.”

Celebes by Max Ernst, 1921. Tate

So the Elephant, then. Apparently, he also goes by the name of Pulcino di Minerva, Minerva’s chick, or perhaps baby owl? Another derivation might be Pulcinella, the comic character inspired by the real-life Paoluccio della Cerra, whose face survives in a portrait by Ludovico Carracci. According to Piero Toschi, the word Pulcinella goes back to the 1300s, meaning clown or buffoon. There was a real ancestry to Bernini’s elephant, Grossman tells us, in the shape of Don Diego, an elephant that had arrived in Rome in May 1630, causing understandable commotion. Another elephant, by the name of Hanno, had been given to Pope Leo X by King Manuel of Portugal in exchange for tribute relief or other papal favours. Hanno died three years later from constipation, for which he had been administered “a half a kilo of gold in a laxative”. He was drawn by Raphael, who was commissioned to design a life-size memorial fresco in his honour. Hansken, a female elephant, also toured Europe around that time, her portrait this time drawn by Rembrandt, and King Manuel would send a replacement pachyderm to Leo, a rhinoceros called Ganda, which died before its arrival in a shipwreck on the way. His body would be taxidermically preserved and safely delivered to the Pope. Bernini himself had tackled a number of elephant projects in his lifetime, and would recycle designs, and he was as keen to make the most of the symbolic powers of obelisks, their exoticism and their imperial aura, as was Pope Alexander. Elephant and Obelisk is not mentioned by Bernini’s two contemporary biographers, yet Grossman is riveting in his analysis of the evolution of the ideas involved, the new archaeological thrill of antique finds that kept popping up as Romans rummaged through their city’s soil, the colossal feats of engineering involved, across the millennia, for their transport, installation, resurrection.

Grossman does not mention the work of Giorgio de Chirico, whose house and studio were by the Spanish Steps in Rome, a few minutes away from Bernini’s elephant. De Chirico uses industrial chimneys in several of his works to reference obelisks in terms of both urban history and social symbolism (The Mute Orpheus; The Anguish of Departure; Piazza d’Italia con Statua; Piazza d’Italia con Uomo Politico; The Enigma of a Day…) The Minerva Elephant and Obelisk monument has a distinct surreal quality to it, and perhaps some of its diachronic fascination is due to that mischievous eccentricity and polysemy. One might also have concluded this peregrination through art and history with Max Ernst’s Celebes, which bears, according to some art critics, the clear influence of de Chirico, and – who knows? – perhaps it is also a roguish reference to Bernini…

Loyd Grossman is an entrepreneur, author and broadcaster. Born in Boston in 1950, he began his career as a journalist writing for music publications including Rolling Stone, Fusion and Vibrations whilst studying as an undergraduate at Boston University. He went on to work for Harpers & Queen and The Sunday Times before becoming a writer and presenter. He has a lifelong interest in history, the arts and heritage, receiving a PhD from the University of Cambridge and serving on the board of a number of cultural institutions including English Heritage, the British School at Rome and the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. He is Chairman of The Royal Parks, President of The Arts Society and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. His books include Benjamin West and the Struggle to be Modern (Merrell, 2015). An Elephant In Rome: Bernini, the Pope, and the Making of the Eternal City is published by Pallas Athene.

Loyd Grossman is an entrepreneur, author and broadcaster. Born in Boston in 1950, he began his career as a journalist writing for music publications including Rolling Stone, Fusion and Vibrations whilst studying as an undergraduate at Boston University. He went on to work for Harpers & Queen and The Sunday Times before becoming a writer and presenter. He has a lifelong interest in history, the arts and heritage, receiving a PhD from the University of Cambridge and serving on the board of a number of cultural institutions including English Heritage, the British School at Rome and the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association. He is Chairman of The Royal Parks, President of The Arts Society and a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society. His books include Benjamin West and the Struggle to be Modern (Merrell, 2015). An Elephant In Rome: Bernini, the Pope, and the Making of the Eternal City is published by Pallas Athene.

Read more

loyd-grossman.com

pallasathene.co.uk

@Pallas_books

@loydgrossman

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika