Nicolasito

by Pilar Quintana

“Pilar Quintana uncovers wounds we didn’t know we had, shows us their beauty, and then throws a handful of salt into them.” Yuri Herrara

Tío Eliécer had owned the bluff until the seventies, when he divided it into four lots and put them up for sale. He had raised Damaris, because the man who got her mother pregnant – a soldier doing his military service in the region – abandoned her when she got knocked up, and in order to support her daughter she had to work as a live-in, keeping house for a family in Buenaventura. She sent money whenever she could and came back for Christmas, Semana Santa, and sometimes for long weekends. Damaris was raised in a shack that Tío Eliécer and Tía Gilma owned, on the land that now belonged to Señora Rosa – the first lot they sold. They sold the adjacent land next, to an engineer from the city of Armenia, and the lot behind it to the Reyes family.

The Reyes family was made up of Señor Luis Alfredo, who was from Cali but lived in Bogotá; his wife Elvira, who was from Bogotá; and their son Nicolasito. They had a big house built entirely of sheet metal – the most modern construction material at the time – with a pool and a large gazebo that had a sink and a wood-fire grill where they could make sancocho and asado and have parties. And a wooden shack for the caretakers. Damaris’s family moved onto the plot that hadn’t yet sold, which bordered the Reyeses’. Because the Reyes family spent all their vacations there, Nicolasito and Damaris became friends. They were the same age and born on the same day, a terrible day for a birthday: January 1.

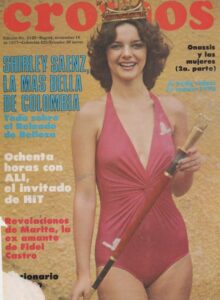

It was December. The town still didn’t have electricity back then, Shirley Sáenz was crowned the new Miss Colombia, and Damaris and Luzmila spent ages admiring her in the Cromos magazines Señora Elvira brought up from Bogotá. Nicolasito used to pretend he was an explorer and organize expeditions on the bluff, expeditions on which Damaris acted as guide and they carried flashlights even though it was daytime.

They were about to turn eight. Most of the time Luzmila went with them, but that day she threw a hissy fit when they said she couldn’t lead the expedition, flung to the ground the stick she carried to fend off snakes, and went home whining.

Damaris and Nicolasito made it to their destination, a low rocky headland where the waves licked at the bluff. At first they were transfixed, watching leafcutter ants descend a tree single file, transporting pieces of foliage. They were big, red and hard, with pointy things on their heads and bodies. “It looks like they’re wearing armor,” Nicolasito said. Then he walked over to the rocks, saying he wanted to feel the spray of the waves on his face. Damaris tried to stop him, explained that it was dangerous, told him that the rocks there were slippery and the sea treacherous. But he didn’t listen and went and stood on the rocks, and the wave that crashed just then, a violent wave, carried him off.

Her feet sank into the dead leaves and got buried in the mud, and she began to feel like the breathing she could hear was not her own but that of the jungle, and that it was she and not Nicolasito who was drowning.”

The image remained engraved in Damaris’s mind: a tall, white boy standing face to the sea, followed by the white crest of the wave, and then nothing – empty rocks above a green sea, which looked calm in the distance. And her, there by the leafcutter ants, unable to do a thing.

Damaris had to return alone, through a jungle that seemed denser and darker than ever. The treetops above her formed a solid canopy, and the roots below snarled together. Her feet sank into the dead leaves carpeting the ground and got buried in the mud, and she began to feel like the breathing she could hear was not her own but that of the jungle, and that it was she and not Nicolasito who was drowning in a green sea full of leafcutters and foliage. She wanted to run away, get lost, say nothing to anyone, be swallowed up by the jungle. She started to run, tripped and fell, got up and ran again

When Damaris reached the Reyeses’ property, she found Tía Gilma inside the shack, talking to the caretakers. Tía Gilma listened to what Damaris recounted, didn’t utter a single word of reproach, and took charge of everything. She asked the caretakers to go out in the canoe to search for Nicolasito and went to tell Señora Elvira what had happened herself. Señor Luis Alfredo was out deep-sea fishing, so Señora Elvira was alone at the house. Tía Gilma went inside and Damaris stayed outside on the veranda. There was no wind. The leaves on the trees were still and the only sound was that of the sea. To Damaris it felt as if time was stretching, as if she would be there on the veranda until she grew up and then grew old.

Finally they emerged. Señora Elvira was like a crazy person. She shouted, sobbed, crouched down to Damaris, stood up, paced the veranda, gesticulated, asked a question and then another one, and then asked the same thing again in a slightly different way. Damaris no longer remembered what it was she asked, but did remember her face, and the anguish in her eyes, which were blue with the little veins burst and blood staining the whites.

That day they searched for Nicolasito until nightfall and kept searching tirelessly every day after that. Tío Eliécer was helping with the search and, in the afternoons, when he came back with the bad news, he’d sit on a tree trunk by the door to the shack. Damaris knew that this was the sign for her to approach. She did so without dawdling, as she didn’t want him to get any madder than he already was. Then her uncle would grab a hard, flexible switch cut from a guayaba tree and whip her. Tía Gilma had told her not to tense up, that the more she relaxed her thighs, which was where her uncle struck her, the less it would hurt. She tried, but fear and the cracking of the first lash made her clench every muscle tight, and each new blow hurt more than the last. Her thighs looked like the back of Christ. The first day he’d given her one lash, the second two, and so on, adding one for each day Nicolasito didn’t turn up.

Tío Eliécer stopped on the day that he would have given her thirty-four lashes. Thirty-four days had gone by, longer than the sea had ever taken to return a body. The skin had decomposed from the salt and sun, been eaten down to the bone by fish in some places, and, according to those who were there, the body reeked.

Tía Gilma, Luzmila, and Damaris went to the bluff to watch. A body that now looked smaller, the tiny body of a boy, there on the sand, and Señora Elvira, so blonde, so thin, so pretty, lifting it up a little in order to embrace her son and cover him in kisses as though he were still handsome. Tía Gilma put her arm around Damaris, and then Damaris couldn’t take it anymore and burst into tears for the first time since the tragedy.

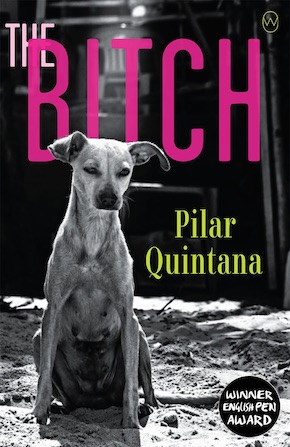

From The Bitch (World Editions, £9.99)

Pilar Quintana was born in Cali, Colombia, in 1972 and studied at the Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. She debuted with Cosquillas en la lengua (Tickles in the Tongue) in 2003, and published Coleccionistas de polvos raros (Collectors of Weird Screws) in 2007, the same year the Hay Festival selected her as one of the most promising young authors in Latin America. Her latest novel, La Perra (The Bitch), won the 2018 Colombian Biblioteca de Narrativa Prize. The first of her works to be published in English, The Bitch is out now in paperback and eBook from World Editions, translated by Lisa Dillman.

Pilar Quintana was born in Cali, Colombia, in 1972 and studied at the Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá. She debuted with Cosquillas en la lengua (Tickles in the Tongue) in 2003, and published Coleccionistas de polvos raros (Collectors of Weird Screws) in 2007, the same year the Hay Festival selected her as one of the most promising young authors in Latin America. Her latest novel, La Perra (The Bitch), won the 2018 Colombian Biblioteca de Narrativa Prize. The first of her works to be published in English, The Bitch is out now in paperback and eBook from World Editions, translated by Lisa Dillman.

Read more

@pili_quintana

@WorldEdBooks

Author portrait © Danilo Costa

Lisa Dillman is based in Decatur, Georgia, where she translates Spanish, Catalan and Latin American writers and teaches at Emory University. Her recent translations include Andrés Barba’s Such Small Hands (winner of the 2018 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Award); Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World (winner of the 2016 Best Translated Book Award), Kingdom Cons and The Transmigration of Bodies (shortlisted for the 2018 Dublin Literary Award); and Víctor del Árbol’s Breathing Through the Wound and A Million Drops.