Message in two suitcases

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“Poignant, witty and heart-rending. There’s never a dull moment.” Kristien Hemmerechts

There is an old Urdu/Hindi word that would suit well this explosively funny, irresistible, and profoundly tragic human comedy: lifafa/lifaafaa, a term that can mean a bag, an envelope, a wrapper or a cover, anything frail, or an outward show. Mama Tandoori is all of these and indeed much more, a surging personal narrative and the singeing, reflective portrait of many lives, many histories; of a ubiquitous and eternally evaded and erased memory, but also of the uncontrollable urge for salvaging and reconstruction. For new beginnings that will follow on old endings.

A boy grows up in Rotterdam, in a family that seems to weld the fiendish with the angelic, tragedy with bliss, pure reason with the utterly irrational, brutal instinctiveness with the trauma of exile, ethnic and religious persecution, dire poverty, the yearning for kindness and the burden of loss. Overpowering ambition (whether for an illustrious mention as the very last customer of a local grocer succumbing to a giant retailer, or for a gold medal in athletics in the 6 to 7 age group at the local sports club, for sons who are doctors or economists rather than writers or environmental scientists) is matched by fragile emotional equilibria and quiet genius. People and objects must cohabit a space of highly symbolic, blushingly embarrassing, deeply moving clutter, a hoarder’s lair of material possessions and bequests, of memories stuffed in dusty corners, of unbearable vital weights that will keep not one but many lives grounded and rooted – on occasion crushing and pulverising them for good measure, and with a hefty dose of bitter wit that is filled with almost transcendental perseverance.

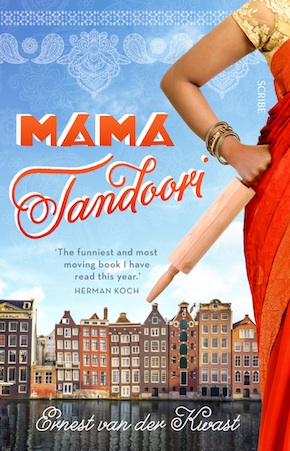

A young Indian nurse called Veena emigrates to the Netherlands in 1969; she carries with her two suitcases full of trinkets – or, depending on the dismal anguish of the source, incalculable treasure. She also carries the shards of a broken heart, from an abortive romance that never happened – except in a version of surreal authenticity that surpasses any Bollywood production, past or future. She marries a Dutchman of old stock and even older habits, idiosyncrasies, emotional dynamics and humanity. For the first and last time in her life she will capitulate to another’s desires, and utter, albeit reluctantly, the anathema ‘yes’. From that moment on, she will exert full powers of domination over the smaller and wider constellations of her world with an iron fist – or rather with the occasional slipper and the endlessly reappearing, seemingly imperishable rolling pin.

Mama Tandoori leads a chameleonic existence between ‘Mrs van der Kwast’ and her Indian soul, yet to the very last page, she remains indomitably charming, frighteningly endearing, ruthlessly indispensable.”

An Indian rolling pin (or velun) – is long, thin and tapered at the ends, so that rotis and poppadoms can be thin, silky, delectably brittle. Mama Tandoori must make do with the shorter, stockier, more inelegant Western version, just as she must make do with so many other more or less ineffective substitutes for her Indian disposition and perception of the world. And yet, each time, through hell and high water, she manages to achieve almost perfect harmonies, swooning Indian dishes, a concentric universe that even at its most outrageously extreme has never fallen apart. Mama Tandoori leads a chameleonic existence between ‘Mrs van der Kwast’ and her Indian soul, yet if the skin colour reflects alterations of appearance and circumstances, the dissimulations required by cultural and psychological survival, it will never reflect any alteration of the heart. To the very last page, Mama Tandoori remains indomitably charming, frighteningly endearing, ruthlessly indispensable.

Scathing dry humour combines with larger-than-life characters that resemble shadow-theatre puppet figures performing on a 1970s–80s Koothambalam – the heaving, creaking, long-suffering floorboards of the various residences of the van der Kwasts serving more than aptly as the sacred spaces of epic spectacles lost in time and culture. “My eldest brother,” Ernest discloses ruefully, “has learning disabilities. He is the only one who still thinks [our family is] normal.” Yet this intense choreography of stylised sketches, this Indography of mores and tears, also embeds untiringly into the narrative of these lives intermezzos of sheer humanity: “My mother’s distant past is a dark stain. I know little about it; shame keeps her mouth firmly buttoned. But sometimes she wakes at night from a dream about a beggar’s life, many, many years ago.” Veena van der Kwast is ashamed of having been “the last mouth” who had to suckle a goat’s udder to survive; she is terrorised in her darkest recesses by the chronicled collective memory of the displaced, persecuted, massacred and bewildered populations that flooded both sides of the Radcliffe Line immediately following Britain’s partition of the Indian subcontinent, the moment of independence for India and Pakistan. Seventy years on, the scorching brightness of this almost Wagnerian mother conceals a darkness of unhealable pain, past and present. A country devastated in order to subsist in dignity and nationhood, a first-born who will never truly grow into adulthood, a personal state of being in constant conflict between violent silence and the compulsion to be always there, always better than, never erased. These are the demons of Mama Tandoori’s soul, guiding her through life, goading her into uproariously reprehensible acts of smaller or greater consequence.

Jacqueline Blom as Mama Tandoori in the 2012 stage adaptation at the Luxor Theater, Rotterdam. YouTube

We read, incredulous and mesmerised, of Machiavellian schemes for the “obstruction of science”, of a pilgrimage to Lourdes where sufficient faith suffers a rock-hard shock; of hoarding as an impulse, a dictatorial vice, a gesture of the most delicate despair; of free travel passes for those who accompany individuals with learning disabilities, and of the ingenious training methods of early Indian athletes; of lofty dreams of stardom on the Bollywood silver screen, of the inescapable wisdom of Herodotus, and the lethal perils of the Fosbury Flop. We meet the many faces of India past and present, and we are invited (rolling pin balanced precariously over our heads) to ponder over the intricacies of reincarnation and inheritance, interracial relations, the freedom and the loosing of one’s soul. We learn that writers cannot be issued travel visas to India, in contrast to doctors.

The distance created by the mutual incomprehensibility of the parents as individuals, and in their complex relationship, creates a poignant, numbing tension from the start. “My father [had] come to think of himself as dirt poor. It was the easy version of his life. Once upon a time, his wife had arrived from India laden with jewels. She bought a house, followed by another, and yet another. Meanwhile, he earned the salary of a tailor in Bhopal… This version provided peace and quiet, so my father, like other men, could sit on the couch and read his paper without getting assaulted with a rolling pin.” There is a mixture of bravado self-confidence and stinging self-deprecation in Ernest van der Kwast, which obscures an admittedly iconoclastic affection. As a discus thrower, “on field, I could recite Reiner Maria Rilke’s poetry, and this is… a very rare and underrated quality” while his mother on the sidelines cheered so desperately hard that under normal circumstances he would have been instantly and universally disqualified.

The real Veena van der Kwast has called the novel ‘friction’ – cunningly or painfully avoiding the word fiction, yet also revealing a caustic sense of humour that seems to have been one of the most splendid jewels she hid in those two celebrated suitcases. The tone throughout is Gerald Durrell with more depth of focus, a more enhanced, genuine experience of human tragedy and trauma, a more ecumenical scope, and a Nabokovian quality of scourging sarcasm and simulated flippancy. The reader’s challenge is to assess the value of irony, the genuineness of the detachment and the defamiliarising lens. Stylistic, eschatological, ontological and cultural-historical commitment is necessary, just as a desire to indulge in the inner joy of a humanity that will never give up hope. If one maintains an emotive, intellectual and imaginative attachment to the episodes, so that the narrative and semantic thread running through them may reveal the ‘novel’ in Mama Tandoori, rather than evaporate in the ‘novelty’ element of virtuosic ethnic extravaganza, then the reward is great. Stereotypes revert to their etymology of ‘strong types’, and the strength of endurance, the reality of difficulty and the challenge of individual change in the motions of sameness are revealed as the gift of an adversity and paradox that contains much of what is most vital. The curse of being the son of Mama Tandoori becomes a blessing in thin disguise: Ernest van der Kwast’s ordeal transforms into highly engaging mythopoetic prowess, which thrives on this rare inventory of almost fully-fledged dramatis personae yearning, clamouring, brawling for a lavish literary life, for new masks but also for the release of their true faces and personality.

The novel is a tribute of sorts to his parents, and a road map to his own son: on how to handle the miraculous, unbearable weight of the sadness of others who are as appositionally different as they are stiflingly or revitalisingly identical.”

Some corrections to the ‘friction’ merit note: Theodorus van der Kwast, the martyrish father of Ernest, and the husband of Veena, is in fact more famous than his son (at least for the time being). A pathologist and world-leading specialist in nephroblastoma, allogeneic partial hand transplantation of the rhesus monkey and prostate cancer genomics, he is neither bald-headed nor faint-hearted, but fair, congenial and the author of 761 publications in his field with over 31,000 citations to his name. As for Veena, far from burning garbage in the garden to exorcise the demons of writing, she “practically forced the editor to publish my first work,” the author told Vogue Italia. “He absolutely didn’t want to, but he had no chance against my mother. Sooner or later she’ll go to Stockholm and plead my case with the commissioners of the Nobel Prize. She might even convince them.” So it seems that some of the mesmerising, mortifying facts about Ernest, his parents, his siblings and their engrossingly exorbitant Indo-Dutch life might have to be taken with a grano salis.

This is an eccentrically moving story, centrifugal in its impetus, desperately attached and attuned to its intentions. It is a story that is possible only in hindsight, and in leisurely recollection from the standpoint of one’s own attempts at marriage, work and parenthood. Ernest van der Kwast’s novel is tacitly or explicitly in turn a tribute of sorts to his parents, and a road map to his own son: on how to handle the miraculous, unbearable weight of the sadness of others, others who are as appositionally different from us as they are stiflingly or revitalisingly identical. Tragedy is the twin of comedy in Ernest van der Kwast’s world.

In 2012, Mama Tandoori was adapted for the stage. All the actors were white, made up to give them ‘Indian’ features, perhaps a meta-comment on the novel’s sense of discomfort with presumed types, roles and destinies. The play enhances the cathartic effect of the novel’s almost hyperreal performative theatricality, and confirms its very deep, cantankerous humanity: at the end of the promotional trailer, the author’s mother, the impossibly real Mama Tandoori, wishes the play and the actors “good luck” with the most captivating smile. In her raised hand, she holds her rolling pin, as if to say “… or else.” In a similar vein, the novel fluidly and daringly counterbalances talent and pain, splendid form and essential meaning in a new, fragrant and spicy blend poignantly evocative of Dutch India or the Indian Netherlands.

Ernest van der Kwast is a Dutch author born in Mumbai in 1981, who lives between the Netherlands and Italy. Mama Tandoori became a bestseller in the Netherlands and Italy and sold more than 100,000 copies. It is the second of his novels to be published in English after The Ice-Cream Makers (Scribe, 2016). Mama Tandoori, translated by Laura Vroomen, is out now from Scribe.

Ernest van der Kwast is a Dutch author born in Mumbai in 1981, who lives between the Netherlands and Italy. Mama Tandoori became a bestseller in the Netherlands and Italy and sold more than 100,000 copies. It is the second of his novels to be published in English after The Ice-Cream Makers (Scribe, 2016). Mama Tandoori, translated by Laura Vroomen, is out now from Scribe.

Read more

@ernestvdkwast

Laura Vroomen was born in the Netherlands in 1972. After an academic career teaching English Literature and Cultural Studies, she has since translated a range of fiction and non-fiction from Dutch to English, including thrillers, memoirs, and books on politics. She lives and works in London.

lauravroomen.co.uk

@LauraVroomen

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.