Visions and monsters

by Mika Provata-Carlone

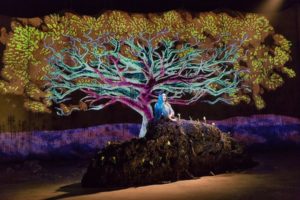

Marta Fontanals-Simmons as Hel in The Monstrous Child, The Royal Opera © 2019 ROH. Photograph by Stephen Cummiskey

The Monstrous Child, which has just completed a very successful run at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre, is one of the first and most audacious examples of a new genre: highly evocative classical opera especially written for teenage audiences. Adapted from the YA novel of the same name by Francesca Simon with music by Gavin Higgins, a libretto by Simon herself, and directed by Timothy Sheader, The Monstrous Child was well positioned to be noticed and to be, especially, a resounding success.

In many ways, in what are perhaps the most significant ways, it has indeed been a sold-out triumph. A spectacular piece of physical theatre, puppetry and heuristic acting, with music that is both monumental and breathtaking in its daring, richness, and unremitting adherence to a formidable classical legacy and tradition, The Monstrous Child is deeply moving, relentlessly human and poignant, a staggering experience.

It is, however, also quite unsettling. Its theme, underneath all the layers of caustic humour and campy double-references, is perception. Its almighty omnipotence and its hellish dominion. It is about male and female perspectives, power and self-definition, about isolation, anger, centres and margins. It is also about cultural highs and lows, stereotypes and real substance. A scathing commentary on conjugal and parental relationships, on authority and subjection, it looms over the audience a little like one of Louise Bourgeois’ spider mother figures might loom over an unsuspecting Wagner. It is a very disturbing portrayal of the female psyche, of the distortions female identity undergoes, or especially inflicts upon itself. With an emphasis on Jungian archetypes, Norse gothic lore and the Lacanian principle of a gaze that validates or erases, The Monstrous Child contains much food for thought. In terms of realisation, however, the plot can seem longwinded, too reliant on a kitsch version of teenage angst, and as paying too much homage to pop culture and its emptiness, when its aspirations are decidedly high art, and of the very best kind.

The Monstrous Child is unquestionably part of a new era for opera writing, for opera audiences, for an operatic, one might say, perspective of our reality.”

The music and the artistry of the staging, the almost sublime quality of the voices, however, have the power to transport and to enthral. The Monstrous Child is unquestionably part of a new era for opera writing, for opera audiences, for an operatic, one might say, perspective of our reality. It was a pleasure to meet and interview one of the two alternating conductors, Mark Austin, following the performance on Thursday 28 February 2019.

MP-C: Over the past ten years or so, opera has been experiencing a particularly vibrant revival, and in many ways you have been part of it. You have worked both with traditional operas and with new, even eclectic ones, with smaller companies and with the mainstream greats. What can opera mean to us today in your view? How do you feel audiences have changed both in their composition and in their response to the form?

MA: The wonderful thing about opera is that it offers so many ways in. There is always an element that first attracts each audience member: the music, the beauty of the human voice, the storytelling, the visual aspect of the sets and costumes, or even a particular singer. And what does it mean to talk about ‘opera’ after 420 years of the genre. Over the course of this period, the dramatic function of music and the means of expressing emotion were completely transformed. The operas of Handel and Puccini are fundamentally different entities, the one a series of ‘affect’ character arias primarily showcasing the singer’s vocal ability and the other a second-by-second depiction of human emotion.

Marta Fontanals-Simmons as Hel and Dan Shelvey as Baldr in The Monstrous Child, The Royal Opera © 2019 ROH. Photograph by Stephen Cummiskey

Today there is a huge range of possibilities for opera-goers both new and experienced, including much-loved stagings of established masterpieces, challengingly conceptual rethinks of the canon, exciting new additions to the repertoire and a wealth of recorded and video material. The opera industry today offers the possibility of preserving, cherishing and re-examining the cultural past, whilst also refreshing the art form for a new audience. We have to remember that in the 19th century the thrill of opera was mainly based around the novelty of each new premiere. This is something that we have almost completely lost now as the majority of performances are of historical works – this sense of public anticipation is more present in a hotly-awaited film launch. Nonetheless, opera remains a way to depict the joys and sufferings of the human condition that television and film have not fully supplanted. The beauty, fragility and power of a magnificent voice, heard live with an orchestra, is an extraordinary experience.

Audiences range hugely in their approach to opera. There are extremely knowledgeable opera-goers who have an immense love for the form and appreciate the great works of the past and the art of singing in astonishing detail. There are loyal but occasional visitors for whom the total experience, for instance at a summer opera festival, is as important as the work itself. There is a small group of dedicated followers of new opera who actively hunt the novelty, the excitement of breathing in a new work. On the whole audiences today particularly value credible dramatic storytelling, such as we experience in film, and this preconditions the way productions are conceived and expectations are met.

Many companies are seeking to attract younger and more diverse audiences by breaking down some of the former boundaries (knowledge, dress codes, ticket prices). I am excited about all these initiatives and indeed value all audience members who take the risk of purchasing a ticket for an opera. Once they are in their seat it is our job as performers to captivate them, even just for one moment, and give them an experience that briefly causes time to stand still.

It is amazing to perform a new opera to an audience of young people… What is important is that there are as many ways in as possible – it only takes one experience to sow the seed of a lifetime’s exploration.”

Is it new audiences for new operas? Or is it an evolution and transformation on both sides of the podium?

It is amazing to perform a new opera to an audience of young people for whom it is their first experience of the art form. Some of these moments have been the most memorable in my career so far – the instinctive response that many children have to the power of opera is immensely inspiring and reassuring. I am undecided as to whether it is better to create new works for new audiences based on modern stories they already know, or whether to inspire them with some of the great operas of the canon. Certainly, works with stereotypically good and evil characters, such as Rigoletto, are highly accessible to an interested adult opera novice. What is important is that there are as many ways in as possible – it only takes one experience to sow the seed of a lifetime’s exploration.

You have now conducted two new operas that are addressed to a younger generation of opera-goers, Coraline and now The Monstrous Child. The music in both cases has been unabashedly and very excitingly eclectic, uncompromising, determinedly rich, complex and mature. What has the experience been like?

Marta Fontanals-Simmons as Hel in The Monstrous Child, The Royal Opera © 2019 ROH. Photograph by Stephen Cummiskey

I was assistant conductor for Coraline – I didn’t conduct any performances. But working on a new opera is an immense thrill, particularly when the composer and librettist are in the room. As a team, everyone is creating something completely new and the discussions that this involves are incredibly collaborative. There are particular issues to solve: maybe the stage director needs some more time in a particular bar for emotional credibility in a dialogue, or a certain musical passage sits in an inappropriate range for a particular singer’s voice. Both composers I recently had the honour to work with – Gavin Higgins and Mark-Anthony Turnage – instinctively understand the requirements of theatre. Their willingness to alter their own carefully-crafted scores in the rehearsal room is a far cry from the inauthentically inviolate status we now attach to works by Mozart or Rossini.

Your own background as a musician and as a conductor is quite unusual. You came to music by way of literature and philosophy, which gives you a rather unique insight into the relationship between story and representation, words and sound, between the dramatic experience and the human reality. As a conductor, you have always placed music in a broader creative context. How would you describe this broader context with regard to The Monstrous Child?

I am fortunate to have had music in my life from age 4, when I began learning the violin, and music has always sat at the centre of my life alongside my other studies. For me the cultural context of any particular work offers the performer a great help in getting to the heart of what it is aiming to say.

The Monstrous Child the novel is Francesca Simon’s typically inventive and energetic re-imagining of elements of Norse myth. This is such a large cultural tradition that I had to prioritise my own preparation to what would directly affect and improve my ability to conduct the opera. I carefully read her novel, which is of course the main source text. This enabled me to see and admire how Simon, as the librettist, together with composer Gavin Higgins, had prepared the libretto by trimming the story and focusing on the key characters and plot corners. Behind any operatic telling of this myth sits Wagner’s Ring, which is an enormously influential work dealing with the same material. However, it is not particularly relevant to The Monstrous Child – there is only one direct musical allusion to Wagner’s music – as the story has its own colour in Simon’s novel and Higgins is influenced by a number of different composers, including Britten, Puccini, Stravinsky, Ades, Turnage…

The Monstrous Child the novel is Francesca Simon’s typically inventive and energetic re-imagining of elements of Norse myth. This is such a large cultural tradition that I had to prioritise my own preparation to what would directly affect and improve my ability to conduct the opera. I carefully read her novel, which is of course the main source text. This enabled me to see and admire how Simon, as the librettist, together with composer Gavin Higgins, had prepared the libretto by trimming the story and focusing on the key characters and plot corners. Behind any operatic telling of this myth sits Wagner’s Ring, which is an enormously influential work dealing with the same material. However, it is not particularly relevant to The Monstrous Child – there is only one direct musical allusion to Wagner’s music – as the story has its own colour in Simon’s novel and Higgins is influenced by a number of different composers, including Britten, Puccini, Stravinsky, Ades, Turnage…

The rarity of new opera commissions means that the broader context of any new opera is not only its genesis or its relation to its source materials, but rather how it sits alongside other recent commissions. There is a genuine hunger in the opera community for successful new work (by which we loosely mean a piece which is dramatically and musically convincing to both an expert and a lay audience, allowing for commercial viability), and so the initial reception of each premiere helps to define what we currently think of as successful new opera writing.

Finally, I would add that as a performer my job is to channel the expressive power of any work to the maximum, and so sometimes reflecting critically can be less rather than more helpful. Simon alters the original dark ending of the Norse myth and allows a quasi-Judeo-Christian moment of rebirth to occur. This bold gesture can affect the reader/audience in different ways. The conductor’s job is not to question whether the abandonment of the dark worldview is credible, or indeed well handled, but instead to draw out the threads that make it possible and to make it my own in performance.

The Linbury as a space is one of a kind – in terms of intimacy, acoustics, aesthetics, artistic possibilities. How did it feel working there?

This was the first opera to be put on in the newly renovated Linbury Theatre at the Royal Opera House. It is an elegant, intimate space and it was a thrill to be involved in the first production there. We worked very hard to explore the acoustic, which varies considerably depending on where you are sitting, and a key part of our work is to balance things with the orchestra to ensure that the text comes across clearly from the stage to the audience. The Monstrous Child is a technically complex production by Tim Sheader and offered a good showcase for what is possible in the Linbury, whether this regards music, lighting, video animation, special effects, etc. I never cease to be amazed at the multitasking and calm discipline of the backstage team, who had to cope with very quick costume changes, challenging music for finding cues, and some very timing-sensitive actions. Conducting at the Royal Opera has been a dream come true for me, and all the more so alongside such a brilliant cast and production team.

What is the future for opera in your view?

The opera industry is full of creative people seeking new directions, commissioning new works and finding ways to keep the existing repertoire alive for each generation. If we peer forward a couple of centuries it is hard to see now how the pace of musical and dramatic development that took place over the 19th and 20th centuries could be sustained in the future. There are now no new chords to be discovered! However, it is likely that technological innovation will play a larger role in the theatrical experiences of the future. Imagine a virtual reality experience where you could walk around on stage during an opera, or even pretend to be one of the characters.

The other important question is whether there will continue to be audience support, and whether future generations of politicians, business leaders and civil servants will consider opera’s financial subsidy to be worthwhile. While the economic and cultural elites will always value opera, that is not enough for it to flourish, nor should this life-enhancing art form be inaccessible to the majority of the population. This is a question of music and drama education – does every child have the opportunity to come into regular contact with music, theatre and opera? – and here the situation looks less promising although not completely bleak. Cinema broadcasts have certainly widened the potential audience (possibly at the expense of less high-quality amateur companies).

Mark Austin was a violinist in the National Youth Orchestra while at school, and later studied at Cambridge University and the Royal Academy of Music, where he was a Junior Fellow. His conducting highlights include Le nozze di Figaro for Dartington International Festival, Goyescas for the Grange Festival, Tosca for Musique Cordiale International Festival and a two-concert Brahms residency with Guy Johnston and the Faust Chamber Orchestra at Hatfield House. As a pianist, he has performed at venues including Wigmore Hall, Kings Place, St John’s Smith Square, Holywell Music Room, Paris’s Opéra Bastille and the Shanghai Oriental Arts Centre. He is musical assistant to The Bach Choir, and regularly conducts them in concerts and in the recording studio.

Mark Austin was a violinist in the National Youth Orchestra while at school, and later studied at Cambridge University and the Royal Academy of Music, where he was a Junior Fellow. His conducting highlights include Le nozze di Figaro for Dartington International Festival, Goyescas for the Grange Festival, Tosca for Musique Cordiale International Festival and a two-concert Brahms residency with Guy Johnston and the Faust Chamber Orchestra at Hatfield House. As a pianist, he has performed at venues including Wigmore Hall, Kings Place, St John’s Smith Square, Holywell Music Room, Paris’s Opéra Bastille and the Shanghai Oriental Arts Centre. He is musical assistant to The Bach Choir, and regularly conducts them in concerts and in the recording studio.

mark-austin.net

@Mark_Aus_tin

Francesca Simon is known for the staggeringly popular Horrid Henry series, whose books and CDs have sold over 20 million copies in the UK alone and are published in 27 countries. She is also the author of the picture book Hack and Whack. She lives in North London with her family. The Costa-shortlisted The Monstrous Child is published by Faber & Faber.

Read more

francescasimon.com

@simon_francesca

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

The Monstrous Child was staged at the Royal Opera House’s Linbury Theatre from 21 February to 3 March 2019 as part of the Winter 2018/19 season.

Read more