A wager

by André Alexis

“A beautifully written allegory for our times… philosophy given a perfect form.” Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize jury

One evening in Toronto, the gods Apollo and Hermes were at the Wheat Sheaf Tavern. Apollo had allowed his beard to grow until it reached his clavicle. Hermes, more fastidious, was clean-shaven, but his clothes were distinctly terrestrial: black jeans, a black leather jacket, a blue shirt.

They had been drinking, but it wasn’t the alcohol that intoxicated them. It was the worship their presence elicited. The Wheat Sheaf felt like a temple, and the gods were gratified. In the men’s washroom, Apollo allowed parts of himself to be touched by an older man in a business suit. This pleasure, more intense than any he had known or would ever know again, cost the man eight years of his life.

While at the tavern, the gods began a desultory conversation about the nature of humanity. For amusement, they spoke ancient Greek, and Apollo argued that, as creatures go, humans were neither better nor worse than any other, neither better nor worse than fleas or elephants, say. Humans, said Apollo, have no special merit, though they think themselves superior. Hermes took the opposing view, arguing that, for one thing, the human way of creating and using symbols, is more interesting than, say, the complex dancing done by bees.

– Human languages are too vague, said Apollo.

– That may be, said Hermes, but it makes humans more amusing. Just listen to these people. You’d swear they understood each other, though not one of them has any idea what their words actually mean to another. How can you resist such farce?

– I didn’t say they weren’t amusing, answered Apollo. But frogs and flies are amusing, too.

– If you’re going to compare humans to flies, we’ll get nowhere. And you know it.

In perfect though divinely accented English – that is, in an English that every patron at the tavern heard in his or her own accent – Apollo said

– Who’ll pay for our drinks?

– I will, said a poor student. Please, let me.

Apollo put a hand on the young man’s shoulder.

– My brother and I are grateful, he said. We’ve had five Sleemans each, so you’ll not know hunger or want for ten years.

The student knelt to kiss Apollo’s hand and, when the gods had gone, discovered hundreds of dollars in his pockets. In fact, for as long as he had the pants he was wearing that evening, he had more money in his pockets than he could spend, and it was ten years to the instant before their corduroy rotted to irrecoverable shreds.

The dogs, of course, already possessed a common language stripped to its essence. All of them understood its crucial phrases and thoughts: ‘forgive me,’ ‘I will bite you,’ ‘I am hungry.’”

Outside the tavern, the gods walked west along King Street.

– I wonder, said Hermes, what it would be like if animals had human intelligence.

– I wonder if they’d be as unhappy as humans, Apollo answered.

– Some humans are unhappy; others aren’t. Their intelligence is a difficult gift.

– I’ll wager a year’s servitude, said Apollo, that animals – any animal you choose – would be even more unhappy than humans are, if they had human intelligence.

– An earth year? I’ll take that bet, said Hermes, but on condition that if, at the end of its life, even one of the creatures is happy, I win.

– But that’s a matter of chance, said Apollo. The best lives sometimes end badly and the worst sometimes end well.

– True, said Hermes, but you can’t know what a life has been until it is over.

– Are we speaking of happy beings or happy lives? No, never mind. Either way, I accept your terms. Human intelligence is not a gift. It’s an occasionally useful plague. What animals do you choose?

As it happened, the gods were not far from the veterinary clinic at Shaw. Entering the place unseen and imperceptible, they found dogs, mostly: pets left overnight by their owners for one reason or another. So, dogs it was.

– Shall I leave them their memories? asked Apollo.

– Yes, said Hermes.

With that, the god of light granted ‘human intelligence’ to the fifteen dogs who were in the kennel at the back of the clinic.

Somewhere around midnight, Rosie, a German shepherd, stopped as she was licking her vagina and wondered how long she would be in the place she found herself. She then wondered what had happened to the last litter she’d whelped. It suddenly seemed grossly unfair that one should go through the trouble of having pups only to lose track of them.

She got up to have a drink of water and to sniff at the hard pellets that had been left for her to eat. Nosing the food around in its shallow bowl, she was perplexed to discover that the bowl was not dark in the usual way but had, rather, a strange hue. The bowl was astonishing. It was only a kind of bubble-gum pink, but as Rosie had never seen the colour before, it looked beautiful. To her dying day, no colour ever surpassed it.

She got up to have a drink of water and to sniff at the hard pellets that had been left for her to eat. Nosing the food around in its shallow bowl, she was perplexed to discover that the bowl was not dark in the usual way but had, rather, a strange hue. The bowl was astonishing. It was only a kind of bubble-gum pink, but as Rosie had never seen the colour before, it looked beautiful. To her dying day, no colour ever surpassed it.

In the cell beside Rosie’s, a grey Neapolitan mastiff named Atticus was dreaming of a wide field, which, to his delight, was overrun by small, furry animals, thousands of them – rats, cats, rabbits and squirrels – moving across the grass like the hem of a dress being pulled away, just out of his reach. This was Atticus’s favourite dream, a recurring joy that always ended with him happily bringing a struggling creature back to his beloved master. His master would take the thing, strike it against a rock, then move his hand along Atticus’s back and speak his name. Always, the dream always ended this way. But not this night. This night, as Atticus bit down at the neck of one of the creatures, it occurred to him that the creature must feel pain. That thought – vivid and unprecedented – woke him from sleep.

All around the kennel, dogs woke from sleep, startled by strange dreams or suddenly aware of some indefinable change in their environment. Those who had not been sleeping – it is always difficult to sleep away from home – got up and moved to the doors of their cells to see who had entered, so human did this silence feel. At first, each of them assumed that his or her newfound vision was unique. Only gradually did it become clear that all of them shared the strange world they were now living in.

A black poodle named Majnoun barked softly. He stood still, as if contemplating Rosie, who was in the cage facing his. As it happened, however, Majnoun was thinking about the lock on Rosie’s cage: an elongated loop fixed to a sliding bolt. The long loop lay between two pieces of metal, effectively keeping the bolt in place and locking the cage door. It was simple, elegant and effective. And yet, to unlock the cage, all one had to do was lift the loop and push the bolt back. Standing on his hind legs and pushing a paw out of his cage, Majnoun did just that. It took him a number of attempts and it was awkward, but after a little while his cage was unlocked and he pushed the door open.

Though most of the dogs understood how Majnoun had opened his cell, not all of them were capable of doing the same. There were various reasons for this. Frick and Frack, two Labrador yearlings who had been left overnight for neutering, were too young and impatient for the doors. The smaller dogs – a chocolate teacup poodle named Athena, a schnauzer named Dougie, a beagle named Benjy – knew they were physically incapable of reaching the bolt and whined their frustration until their cells were opened for them. The older dogs, in particular a Labradoodle named Agatha, were too tired and confused to think clearly and hesitated to choose liberty, even after their doors had been opened for them.

The dogs, of course, already possessed a common language. It was language stripped to its essence, a language in which what mattered was social standing and physical need. All of them understood its crucial phrases and thoughts: ‘forgive me,’ ‘I will bite you,’ ‘I am hungry.’ Naturally, the imposition of primate thinking on the dogs changed how the dogs spoke to each other and to themselves. For instance: whereas previously there had been no word for ‘door,’ it was now understood that ‘door’ was a thing distinct from one’s need for liberty, that ‘door’ existed independently of dogs. Curiously, the word for ‘door’ in the dogs’ new language was not derived from the doors to their cells but came, rather, from the back door to the clinic itself. This back door, large and green, was opened by pushing a metal bar that almost bisected it. The sound of the metal bar, when pushed, was a thick, reverberant thwack. From that night on, the dogs agreed that the word for door should be a click (tongue on upper palate) followed by a sigh.

They were almost instinctively drawn to the lakeshore. Its confluence of reeks was as bewitching to the dogs as the smell of an early-morning bakery is to humans.”

To say that the dogs were bewildered is to understate it. If they were ‘bewildered’ when the change in consciousness came over them, what were they when, all having left the clinic by the back door, they looked out on Shaw Street and suddenly understood that they were helplessly free, the door to the clinic having closed behind them, the world before them a chaos of noise and odour whose meaning now mattered to them as it had never mattered before?

Where were they? Who was to lead them?

For three of the dogs, the strange episode ended here.

…

The twelve who set out from Shaw were driven as much by confusion as anything else. The world seemed new and marvellous and yet it was familiar and banal. Nothing should have surprised them, yet everything did. The pack moved warily, going south on Strachan: over the bridge, down to the lake.

They were, it has to be said, almost instinctively drawn to the lakeshore. Its confluence of reeks was as bewitching to the dogs as the smell of an early-morning bakery is to humans. There was, first, the lake itself: sour, vegetal, fishy. Then there was the smell of geese, ducks and other birds. More enticing still, there was the smell of bird shit, which was like a kind of hard salad sautéed in goose fat. Finally, there were more evanescent whiffs: cooked pork, tomatoes, grease from cow’s meat, corn, bread, sweetness and milk. None of them could resist it, though there was little shelter by the lake, few places to hide if masters came for them.

None could resist the lake, but it occurred to Majnoun that they should. It occurred to him that the city was the worst place for them to be, filled as it was with beings that feared dogs who would not do their bidding. What they needed, thought Majnoun, was a place where they would be safe until they decided on a course that was good for all of them. It also occurred to him that Atticus, who was at the head of the pack, was not necessarily the one to lead. It wasn’t that he himself wanted to lead. Though he was swept up in the present adventure and fairly happy to be with the others, Majnoun was more comfortable around humans. He did not trust other dogs. This made the thought of leadership unpleasant to him. The true things – food, shelter, water – would have to be dealt with by all, but who would lead, and whom would he choose to follow?

It was dark, though the moon fell out of its pocket of clouds from time to time. Four in the morning, the world full of shadows. The gates to the Canadian National Exhibition loomed as if they might totter and crush anything beneath them. There were not many cars, but Majnoun waited for the green light at the bottom of the street. Half of the pack – Rosie, Athena, Benjy, an Albertan mutt named Prince and a Duck Toller called Bobbie – waited with him. The other half – Frick, Frack, Dougie, Bella the Great Dane, and a mutt named Max – blithely crossed the boulevard with Atticus.

Once they had all crossed, the dark and shushing lake lay before them, while along the promenade lay various types of dung, various bits of food, and other things to be sniffed out. Atticus, a crumpled-face dog whose instinct was to hunt, could also feel the presence of small animals, rats and mice most likely, and he wanted to go after them. He exhorted the others to hunt with him.

– Why? asked Majnoun.

The question – asked with an innovation of the dogs’ common language – was stunning. Atticus had never considered that it might be right to hold himself back from rats, birds or food. He considered the ‘why?,’ distractedly licking his snout as he did. Finally, innovating in language himself, he said

– Why not?

Frick and Frack, delighted, immediately agreed.

– Why not? they asked. Why not?

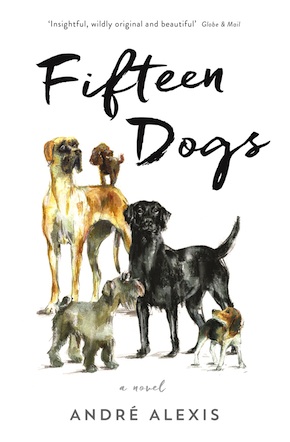

This is an edited extract from the opening chapter of Fifteen Dogs, out now from Serpent’s Tail.

André Alexis was born in Trinidad, grew up in Ottowa and currently lives in Toronto. His previous books include Childhood, Asylum, Beauty and Sadness, Ingrid & the Wolf and Pastoral. Fifteen Dogs, published by Serpent’s Tail in paperback, won the 2015 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Read more.

André Alexis was born in Trinidad, grew up in Ottowa and currently lives in Toronto. His previous books include Childhood, Asylum, Beauty and Sadness, Ingrid & the Wolf and Pastoral. Fifteen Dogs, published by Serpent’s Tail in paperback, won the 2015 Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Read more.

Author portrait © Hannah Zoe Davison