We and our cats

by Ginny Tapley TakemoriI am writing this now in my home in rural Ibaraki, just north of Tokyo, which I share with my husband and our three cats. We bought this old house ten years ago, did a major renovation on it, and moved in just over eight years ago. As we were moving in, one of our new neighbours asked me if we wanted a kitten – or three. Their feral mother had been run over, and our neighbours had taken pity on the kittens, which they had been keeping in a cage in their company office for a couple of weeks. There had originally been five kittens, but they could only find three – two had disappeared, probably taken by crows or one of the many wild animals we get in this area. They were tiny, probably only about six weeks old, which meant they had lost their mother at about four weeks. It is generally recommended that kittens stay with their mothers until at least eight weeks of age.

As it happened, we had thought of getting a cat or two eventually, once we’d settled in (we’d both grown up with cats), but now we found ourselves unpacking while three tiny kittens (“We can’t separate them,” my husband said – obviously I married the right man) were enjoying shredding our beautiful newly papered shoji screens (and we had a lot of them to shred). Now they are huge mature cats who are the undisputed rulers of the house (and the lovely washi shoji paper has been replaced with plastic cat-proof fake paper). Just as well they’re cute, we often find ourselves saying.

When I originally moved to Japan to work at a publishing company in Tokyo, I lived in an old shitamachi area that comprised a warren of streets filled with temples, niche museums and craft shops, tiny bars and restaurants – and lots of cats. A favourite izakaya had a magnificent white cat that would sit outside and occasionally deign to be petted, there was a cat museum, you would always see cats dozing in the graveyards, and a large colony of feral cats congregated at the top of the stairs at the end of the main shopping street.

Here you have people taking in abandoned kittens, and feral cats adopting their humans. Humans and cats find companionship together, helping each other to heal. People rescue cats, but cats also save them.”

And just down the road from my apartment was a delightful shop devoted to cats; on sale were all kinds of cat-themed merchandise, from T-shirts to chopsticks holders to all kinds of knick-knacks. The woman who owned the store, which occupied the ground floor of her home, also rescued cats. There were always cats hanging around the shop, including one who was blind, and she would sometimes call me up and say she had rescued some kittens, did I want to come and play with them? Friends and sometimes customers would sit on cushions on the floor sipping green tea, chatting and playing with the kittens – and in this way she would find homes for her rescues. This was long before cat cafes became a thing.

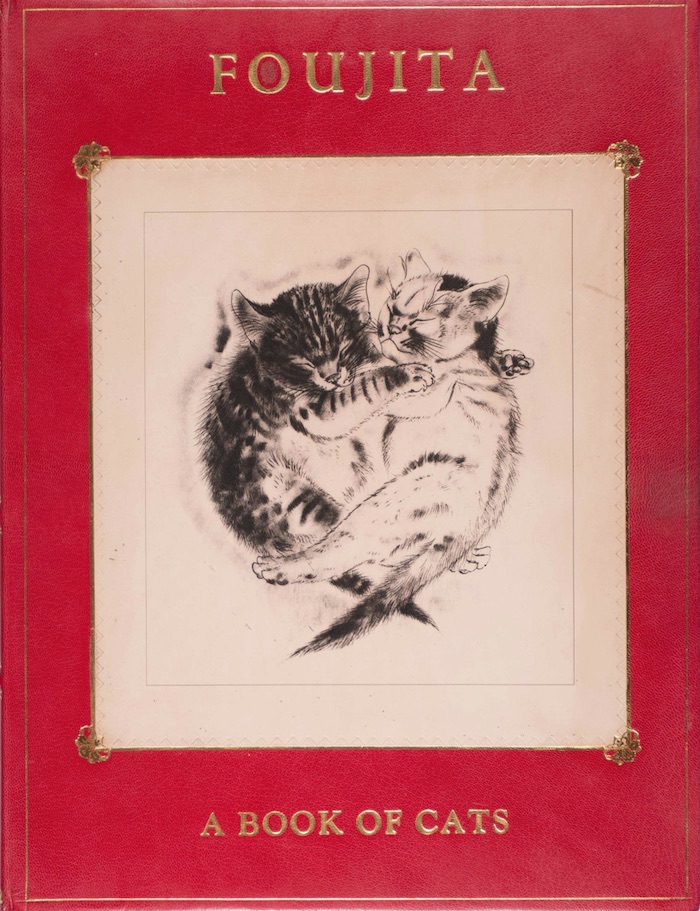

Nowadays cat cafes have become a major tourist attraction, often adding to a problem that most people overlook when admiring Japanese cat culture. The sad truth is that while cats have certainly long been prominently featured in Japanese culture, appearing in literature, art and popular culture, with super cute representations such as Hello Kitty, the Cat Bus in Hayao Miyazaki’s hugely popular animated film My Neighbor Totoro, the early 20th century art of Tsuguharu Foujita, and YouTube star Maru, to mention a few personal favourites, the everyday reality of life for cats in Japan is not always so pretty.

People often don’t neuter their cats, which exacerbates a large feral population, and pet cats are often abandoned (three cats were rescued from the mountain behind my house last year alone), and insufficient animal welfare laws, lack of enforcement and poor general public awareness mean that there is sadly mistreatment too. Life in the wild or on the streets is tough for cats, many don’t live beyond a few years. Most rescue work is done by volunteers, often individuals or small groups, operating on shoestring budgets provided by donations. Municipal shelters do exist, but they are only about animal control: they will keep any animal taken to them for only a week before gassing them. There are organisations actively working to introduce more stringent laws and raise awareness, but it takes time to change laws, not to mention societal attitudes.

In the meantime, pet shops still have cute kittens and puppies on sale – taken from their mothers too young and kept in a cage on display (which often leads to behavioural problems later – and I will leave what happens to those that don’t sell to your imagination). Behind many of these organisations are cruel kitten and puppy mills, where parent animals live only to breed and are then discarded. This is the reality behind the refrain, “Adopt, don’t shop!”

There are good cat cafes, which are often effectively shelters that exist specifically to assist rescue animals and find homes for the cats in their care, but these ones put the welfare of their charges first and are usually by appointment only, limiting the amount of contact cats have with visitors. Less ethical ones can be downright abusive, with no veterinary oversight, overcrowding and lack of proper care, sometimes using restraint and sedation, not to mention the question of where they obtain the cats and what happens to them when the cafe shuts down.

Against this backdrop, I was happy to be asked to translate She and Her Cat. Here you have people taking in abandoned kittens, and feral cats adopting their humans. Humans and cats find companionship together, helping each other to heal. People rescue cats, but cats also save them. I have been delighted to see how this lovely little book has touched the hearts of so many readers in my English translation, and I hope the new paperback edition will help it to reach even more hearts.

—

Ginny Tapley Takemori is the translator of Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman and other prize-winning Japanese fiction. She lives in rural Japan. She and Her Cat, by multi-award winning anime filmmaker Makoto Shinkai and game and anime screenwriter and novelist Naruki Nagakawa, translated into English by Ginny, is published in paperback, eBook and audio download by Penguin/Transworld Digital.

Read more

@penguinukbooks

@TransworldBooks

“A gem, written with deep insight and finely attuned to the ways of cats and their humans. An absolute delight.”

Hazel Prior, author of Call of the Penguins