Welcome to the Green Zone

by Nussaibah Younis

IT’S NOT LIKE I WAS EXPECTING STALINGRAD, but Baghdad took the piss. Arriving for the first time, tucked into a UN car, I watched as the city lights refracted through the bulletproof glass. Floodlights hovered over a pickup football game, square lamps uplit the National Museum, fairy lights dripped down palm trees beside the Tigris River. Why was it so… nice? What happened to the rolling blackouts? The electrical transmission network supposedly ravaged by war? Hadn’t I donated to help the Iraqi women giving birth in cowsheds lit by the flame of a single candle?

Car after car parked along the river’s banks; sparkling Audis and BMWs among older Toyotas and Hyundais. I’d thought I was a high-roller, leaving London halfway through a monthly travelcard. Young men unloaded fold-up chairs, shisha pipes and portable barbeques, setting up by the water’s edge. I could almost smell the marinated baby chickens, the flattened carp smouldering over charcoal, but the driver stopped me from rolling the window down.

‘Security,’ he said, tilting his head towards rooftops empty of snipers.

I spotted a huddle of teenagers watching TikTok, trying to imitate a dance, before pushing each other over, their laughter engulfed by the honking traffic. Rosy and I used to dance like that.

A convoy of cars started beeping frantically, and my back tensed up, anticipating a critical incident ahead. Then I saw white ribbon stretched over the hood of a Mercedes, a bride stepping out, her lace dress draped over marble steps as she entered a five-star hotel. Was this fucking Midnight in Paris? I’d signed up for cluster munitions, not glitter bombs. I spluttered with the indignity of it.

‘Everything OK, ma’am?’ The African driver looked over his shoulder. What had brought him here? A carefully weighed decision, no doubt. Not juvenile heartbreak, like me.

‘I’m fine, thanks. You can call me Nadia.’ I deserved to be called a lot of things, but ma’am wasn’t one of them.

‘Ah, it’s like Nadia Buari, big actress in Ghana.’ He nodded at me with approval. ‘And why you came to Baghdad, Nadia?’

‘Oh, I’m here for a job. I’m creating a deradicalisation programme for ISIS brides. Yeah… don’t ask.’

The driver raised his eyebrows but stayed silent. I checked my phone, hoping for a message from Rosy conveying immense pain at having me ripped from her life. But my SIM card, flabbergasted at having been brought to Iraq, had malfunctioned.

Returning to the window, I strained my eyes, searching for burned-out cars and bullet holes, something to undermine this tableau of festivity, anything to force Rosy into irrelevance. But in the falling darkness, the jollity glowed only brighter.

We entered the Green Zone, a fortified district where international organisations and government agencies hid from the population they claimed to serve. My new home.

I stood in the middle of the room, suitcase next to me, its metal handle standing high, ready to be reversed out of this world. What cunty-bollocking madness had possessed me to come here?”

My driver deposited me in the car park of the UN compound. He stepped out of the car and lit a cigarette, staring hard at my chest while I heaved my suitcase out of the boot. Shouldn’t misogyny have an equal and opposite chivalric force?

‘Over there.’ He pointed towards a security cabin, his burning red tobacco dancing against the darkness.

I dragged my suitcase over the ground, the evening breeze a warm relief after the intense air conditioning in the car. A generator rumbled on the far side of the car park, the smell of diesel repelling insects through the air, the stars obscured by a thin grey smog that hung between the city lights and the night sky.

I entered the security cabin, caught my foot on the lip of the doorway, and fell inside. It usually took more than ten seconds to humiliate myself at a new job, but here I was, already achieving personal bests.

A lean Iraqi man in a blue uniform stepped away from his prayer mat and crouched beside me. ‘You OK, Doctor?’

I was comforted by his use of my title; status gives you scope to absorb minor failures. I hoisted myself up.

‘I’m Farris,’ he said, his Iraqi accent strongly Americanised. He picked up my suitcase and put it on a trestle table that bisected the room. ‘You must be Dr Nadia. You’re very welcome here.’

I watched in horror as he snapped on latex gloves and unzipped my suitcase.

‘Real sorry I have to do this,’ he said, shaking his head. ‘It’s just protocol.’

He used his hand condoms to remove every item in turn. A copy of Cosmopolitan, the headline screaming: ‘Everything you NEED to know about rimming!’ Scores of enormous black underpants interspersed with a few sexy transparent ones. A lilac bullet vibrator, which he unscrewed until a AAA battery shot out. A backup pack of AAA batteries. I pulled out my malfunctioning phone and pretended to text, my ears throbbing with shame.

My ears were familiar with the feeling. When I was a teenager, my mum found a Just Seventeen magazine hidden in a Quranic exegesis textbook in my bedroom. She lay in wait as I returned from school.

‘This is disgusting, Nadia.’ She waved the naked torso of Pacey from Dawson’s Creek in my face. ‘How can you read such filth?’

I don’t read it; I look at it while holding an electric toothbrush to my clit.

‘It’s the other girls at school,’ I said, inching back towards the door. ‘I’m only trying to fit in. I don’t enjoy it.’ Evoking the mysterious dangers of peer pressure normally worked on Mum.

‘If they jumped off a cliff, would you follow?’ she said. It was her favourite retort, but also the most idiotic. I obviously did a risk analysis before deciding which of my friends’ behaviours to imitate. Mum was trying to tear up the magazine, but kept getting the glossy pages tangled in the staples.

‘Muslim friends only from now on,’ she said.

Mum had been a born-again Muslim ever since my father died when I was a toddler. After the magazine incident, she invested heavily in my indoctrination, until I became deeply religious. A total dork, I loved nothing more than planning my revision timetables and being religious was like having a revision timetable for life, the day of judgement being the final exam. I lived as a paragon of Islamic virtue until I went to university, where relentless intellectual challenges and social seductions thawed my devotion to naught.

‘Good to go, Doctor,’ said Farris, zipping my suitcase back up. ‘Look forward to hanging sometime.’

His prayer mat lay in the corner, an image of the Ka‘ba woven into the fabric, but when I looked at his face, it was warm and free of judgement.

He handed me over to a staffer whose white headscarf and blouse produced the combined effect of a shroud – albeit a shroud destined for paradise. It felt strange being around Muslims again, after my godless life in London, and I wondered if they could smell the apostasy on me.

Shroud led me through a grassy outdoor quad, the air fresh against my matted hair, and into a two-storey building where she tapped a key card against a bedroom door. I stepped inside. The room was tiny, which made the furniture look huge. A single bed pushed against the wall, an incongruously ornate wardrobe, a desk covered in blue biro marks, and a flimsy foldout chair.

Shroud held the door open, one foot in, one foot out, and handed me a bundle of items, including a lanyard, a map and a schedule for tomorrow.

‘You have question?’ she said.

Dozens of questions collided in my brain, cancelling each other out.

‘No.’ She was gone before my mouth completed the ‘oh’.

I stood in the middle of the room, suitcase next to me, its metal handle standing high, ready to be reversed out of this world. What cunty-bollocking madness had possessed me to come here?

I remembered the taste of Peroni on Rosy’s tongue, the sweaty jasmine smell she’d leave on my sheets.

I’d thought I could evade my pain, dump it at Heathrow like lost baggage and fly away. Yet here I was, the exact same person who’d left London twelve hours before, my breathing shallow, the oxygen laced with loss.

I persuaded myself to unpack, told myself it’d make the place feel more homely, but ten minutes later, my suitcase was empty and the room remained indifferent to my presence. For the third time in my adult life, I was trying to create a home on hostile terrain. Your mother doesn’t want you, the love of your life doesn’t want you, well… how about a random failed state? Is it possible you belong here?

In the ensuite, I sat on the toilet tracing the cracks in the tiled floor with my toes, my body too tense to wee. It took a concentrated visualisation of Niagara Falls to summon a trickle. I undressed and got into bed. Feeling the rough polyester sheet against my back, I realised it had been a decade since I’d slept in anything other than Egyptian cotton.

‘Princess Nadia,’ Rosy would have said, ‘can you feel a pea beneath your hundred soft mattresses?’

Easy for her to say, bubble-wrapped by her doting parents, taped in the protective seal of a country to which she unequivocally belonged. For years, I’d only had her.

Now I was three thousand miles away, lying in a single bed in Baghdad, clinging to the bedspread despite the heat. My fingers held so lightly to life, I could have shut my eyes and let go, my body evaporating, the world unmoved by such a tiny shift.

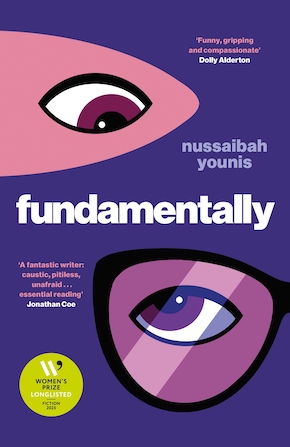

Chapter One, extracted from Fundamentally (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £16.99)

—

Dr Nussaibah Younis is a peacebuilding practitioner and globally recognised expert on contemporary Iraq. For several years, she advised the Iraqi government on proposed programmes to deradicalise women affiliated with ISIS. She has a PhD in International Affairs from the University of Durham, and a BA in Modern History and English from the University of Oxford. As a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington DC, she directed the Task Force on the Future of Iraq and offered strategic advice to US government agencies on Iraq policy. She was a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center, and has published Op-Eds in The Wall Street Journal, the Guardian and The New York Times. She has worked in Washington DC, Dubai, Cairo, Beirut and Baghdad and currently lives in London. Fundamentally, shortlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize, is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in hardback, eBook and audio.

Read more

nussaibah.com

instagram.com/nussaibahyounis

@nussaibah.bsky.social

@wnbooks.bsky.social

“Extremely fascinating, extremely jaw-dropping – and extremely funny.” Marina Hyde