Whit Stillman: All there

by Lucy ScholesYou’d be forgiven for not exactly jumping with joy at the news that yet another Jane Austen adaptation has hit the big screen. This year alone has seen the release of both Burr Steer’s irreverent and rather dubious Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and the publication of Curtis Sittenfeld’s contemporary reimagining of the original, Eligible. Add these to the sizeable collection of adaptations, retellings and mash-ups already out there (including a very popular line in fan fiction bodice-rippers) and Austen would surely be taken aback by the ample legacy she’s left behind. Faced with such a wealth of material, one can’t help but question what exactly – if anything – these new incarnations bring to the originals. Oftentimes, the answer is not much. Plenty of reviewers declared they’d rather read Pride & Prejudice than Sittenfeld’s update, still less the Steer film. But just when Austen mania seems like a lost cause, along comes the most entertaining and original adaptation of them all: the American director and writer Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship, based on Austen’s early, unfinished and thus not widely read epistolary novella Lady Susan.

Kate Beckinsale plays Lady Susan Vernon, a young widow fallen on hard times imposing on friends and relations while ruining marriages and hatching schemes to pair off her poor put-upon daughter Frederica (Morfydd Clark) with the wealthy bumbling idiot Sir James Martin (Tom Bennett). Arriving at Churchill, her late husband’s brother’s Surrey estate, Lady Susan soon has her hostess Mrs Catherine Vernon (Emma Greenwell)’s younger brother Reginald DeCourcy (Xavier Samuel) wrapped around her little finger. Although marriage is Lady Susan’s goal – for both Frederica and herself too – this is no run-of-the-mill romance. Instead it’s a razor-sharp comedy of manners showcasing the talents of a woman of Machiavellian cunning – I doubt even the haughty Mr Darcy would have a hope in hell if Lady Susan set her sights on him.

I’m a passionate fan, therefore I’m doing what a passionate fan would do.”

For some, this foray into late 18th-century English society is something of an unexpected turn for Stillman, a man whose previous films explore the social milieu of the late 20th-century American ‘Urban Haute Bourgeoisie’ – preppy debutantes, well-educated Wasps negotiating the social pressures of college, and yuppies forging their careers – but in reality it’s the perfect match. Think back to his debut feature Metropolitan (1990), when Tom Townsend, an earnest Princeton freshman, and Audrey Rouget argue over the merits of Mansfield Park.

“Nearly everything she wrote is near ridiculous from today’s perspective,” Tom argues, referring to the craziness of a plot that revolves around the immorality of a group of young people putting on a play.

“Has it ever occurred to you that today looked at from Jane Austen’s perspective would look even worse?” Audrey counters.

The joke, of course, is that this is precisely what Stillman’s doing, and has been ever since – Barcelona (1994), The Last Days of Disco (1998) and Damsels in Distress (2011) all explore his obsession with societal structures, manners and mores.

Kate Beckinsale as Lady Susan Vernon and Tom Bennett as Sir James Martin in Love and Friendship. Curzon Artificial Eye

Nevertheless, an actual adaptation is a different beast, and, given the hordes of fans out there ready to jump on any new Austen offering, I’m keen to find out if he found the project at all daunting.

“No, because I’m at the centre of the fan movement myself,” he explained when I sat down with him while he was over for the release of the film. “I’m a passionate fan, therefore I’m doing what a passionate fan would do.”

Generally speaking, he continues, the feedback has been very positive – even when it came to the title (Love & Friendship was actually given to a different early work, but Stillman appropriated it for the film since it goes hand in hand with the likes of Pride & Prejudice and Sense & Sensibility).

Is this because it’s considered an incomplete novel, I wonder? Surely there’s less potential to get it wrong with a novel that’s not so widely known, not to mention much more scope for Stillman himself when it came to writing the script? Apparently, though, when it comes to the exact definitions of these details, that’s where the Austenites can jump in.

“What we say about it is that she concluded it – she put a conclusion in – but she didn’t finish it in the classic Jane Austen sense,” Whitman clarifies. “She was with a lot of her books for a long time, so First Impressions, an epistolary novel, later becomes Pride & Prejudice, a dramatised novel; Elinor & Marianne, an epistolary novel, later becomes the dramatised modern novel Sense & Sensibility; and her parody of Gothic novels, which she originally titled Susan, becomes Northanger Abbey. It’s a process with her, so what I say is yes, she did get to the conclusion in that there’s an end to the story, but it’s clear that had she wanted to continue with it, had she had time to continue with it, she would have done something else, it wouldn’t have been left in this form.”

One of my favourite parts of the job is editing material that’s already there. The form of Lady Susan might not be fully realised, but it contains some of Austen’s best content.”

How different then was the task of completing, then adapting a work-in-progress rather than conceiving and writing a screenplay from scratch?

“It meant the painful moment was postponed,” he says with a laugh. “If you ask me what’s my favourite part of the film making process, my answer is answering people asking the question What’s your favourite part of the film making process? – because that means you’ve done it and someone’s interested in it. The worst part is that bit in-between getting an exciting idea and when you’re finished with it – filling the blank page that’s staring you in the face, or the really lousy things you fill the blank page with at the start that you then have to take out. But in this case it was different because I had really good material to work with.

“One of my favourite parts of the job is editing material that’s already there. I love editing, it’s what I started in – I was in publishing when I started out, then in journalism, and I was much stronger on the editing side than the writing – so getting to edit great Jane Austen! The form of Lady Susan might not be fully realised, but it contains some of Austen’s best content – some of her funniest, best sentences – so it’s not like it was a mediocre project, it was just a project that wasn’t all there.”

Editing, of course, is something of a continuous process, and it turns out that many of the finer details that give the film it’s particular style – and the elements that Stillman is most pleased with – were only added after filming: the character portraits and captions that introduce the narrative, for example, and instances where text is written on the screen.

“Sometimes when you get turned down for funding, I think people are taking the script too seriously. I mean, we’re not going to leave it inert on the page, but you don’t get good editing ideas until you’re editing!”

The film also showcases some inspired casting. Beckinsale is perfectly cast as Lady Susan, but it’s Tom Bennett as the dunderheaded Sir James who steals the most scenes. Stillman describes Bennett as ‘unlocking’ the character during the read-through, so much so that this sent him back to the script to write freshly inspired scenes for the hapless soul, all of which Bennett would again then further transform in the flesh.

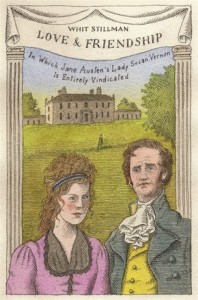

Successful adaptations often earn the praise of having ‘brought the text to life’ but in this instance it’s an accolade that’s even more apt than usual. Bennett’s hilarious performance ensures Sir James is much more vividly realised than the original text allowed, but it also helped inspire Stillman’s novel, Love & Friendship: In Which Lady Susan Vernon is Entirely Vindicated, a version of the story recounted long after the fact by one R. Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, the adoring nephew of the infamous Lady Susan, intent on clearing his beloved aunt of any lingering malicious rumours: “Concerning the Beautiful Lady Susan Vernon, Her Cunning Daughter & the Strange Antagonism of the DeCourcy Family,” declares the title page. Described by Stillman as “a combination of a sort of parody of a nephew writing about his beloved aunt, and the absurd Martin genetics – this Rufus Martin-Colonna turning reality around,” it also draws directly on James Edward Austen-Leigh’s biography of his aunt, A Memoir of Jane Austen (1871). So anyone expecting a straightforward novelisation of the film is actually going to find something far cleverer in their hands.

Successful adaptations often earn the praise of having ‘brought the text to life’ but in this instance it’s an accolade that’s even more apt than usual. Bennett’s hilarious performance ensures Sir James is much more vividly realised than the original text allowed, but it also helped inspire Stillman’s novel, Love & Friendship: In Which Lady Susan Vernon is Entirely Vindicated, a version of the story recounted long after the fact by one R. Martin-Colonna de Cesari-Rocca, the adoring nephew of the infamous Lady Susan, intent on clearing his beloved aunt of any lingering malicious rumours: “Concerning the Beautiful Lady Susan Vernon, Her Cunning Daughter & the Strange Antagonism of the DeCourcy Family,” declares the title page. Described by Stillman as “a combination of a sort of parody of a nephew writing about his beloved aunt, and the absurd Martin genetics – this Rufus Martin-Colonna turning reality around,” it also draws directly on James Edward Austen-Leigh’s biography of his aunt, A Memoir of Jane Austen (1871). So anyone expecting a straightforward novelisation of the film is actually going to find something far cleverer in their hands.

“I had this script that everyone liked – and it’s not every time that you write a script for a film and people enjoy reading it, normally they don’t really, because it’s all ‘interior,’ ‘exterior,’ ‘night,’ ‘day’, all these things that people find a problem – but in our script there was so much to read, so as a reading experience people loved it, and I felt it really was making Lady Susan available to people who don’t like reading epistolary works, and so I tweeted out that I was thinking of doing a novel, and I got a tweet right back from an assistant at a publishing house, so I started talking to them and within a month I had a contract. This was before I knew if I was actually doing the movie, so they weren’t buying the novelisation, they were buying the novel.”

Stillman, it seems, is the master of the multi-layered narrative. It’s not surprising then to hear that he struggled to sign off on the novel. He was still expecting to be allowed another round of edits when he got a phone call from his publishers informing him that finished copies were going to be available in a matter of days.

“It’s like that thing that film editors say: ‘Films are not completed, they’re abandoned,’” he says.

As someone knocks on the door to let us know our time is up, Stillman hurriedly asks whether I enjoyed the various digressions that made it into the finished film. There’s a rather brilliant one regarding punctuation, and another on theology. “I love them,” he says, “and there were even more we couldn’t get in.”

Surely grounds enough for a sequel then, I suggest.

“Yes, brilliant!” he declares beaming as I leave the room.

Whit Stillman’s previous films are Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), The Last Days of Disco (1998) and Damsels in Distress (2011). Love and Friendship is released by Curzon Artificial Eye, and the novelisation is published by Two Roads.

Whit Stillman’s previous films are Metropolitan (1990), Barcelona (1994), The Last Days of Disco (1998) and Damsels in Distress (2011). Love and Friendship is released by Curzon Artificial Eye, and the novelisation is published by Two Roads.

Read more about the film

Read more about the book

Lucy Scholes is a contributing editor to Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer, BBC Culture and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern, Tate Britain, the BFI and Waterstones Piccadilly.

@LucyScholes