Wilde

by Ethel Rohan

“Rohan’s stories are small electric shocks of discovery.” Caroline Leavitt

Inside the Dublin guesthouse, over a breakfast of peppery scrambled eggs, I sat watching the young couple below on the street. They stood on the opposite side of the road, next to the bus stop’s thin yellow pole, bundled up in woollen accessories and thick, dark jackets. They pressed their bodies together, their arms clasping each other’s waist, and rocked from side to side for warmth, their breaths smoke. They put me in mind of Da and his imaginary friend, Mary, waltzing around our kitchen together.

I was alone inside the dining room on Northumberland Road, still jet-lagged on day two of my annual trip back home. Beyond the second-floor window, the grey-black February morning lightened, the sky soon looking wiped clean. The long line of traffic with grasping headlights rolled forward. A giant, naked tree stretched across my bird’s-eye view, its branches sprawling. Like the couple at the bus stop, the tree swayed in constant motion. The wind picked up, battering everything.

I set out from the guesthouse, disappointed the air had stilled. There’s nothing like great gusts, how they blast, clear. At the gate, I turned right. The previous night, I’d turned left on the blackened street and left again onto Haddington Road, discovering shops, pubs, restaurants and a lone laundrette. This right turn would take me over the Grand Canal and should lead straight to Grafton Street, if I remembered rightly. I hesitated, second-guessing myself. I was raised on the Northside, far from this exclusive neighbourhood. I pressed ahead over the canal, deciding to explore. The chill morning was bitter but dry, and I had nowhere I needed to be. I could risk getting lost.

I soon passed Merrion Square Park and stood marvelling through its green railings at the life-size statue of Oscar Wilde. He lay reclining provocatively on a large granite boulder, the bronze monument surrounded by tourists and students, their phones and cameras aimed. The memorial tugged. Up close, Wilde’s black trousers glittered and the collar and cuffs of his green jacket bloomed pink. Now his was a name. Nothing like Mary, as plain as milk. Wilde stared down, managing to look both smug and glum. The blackened flower in his hand made me think of his fairy tale ‘The Happy Prince’. Perhaps the colourless carnation, like the prince, had sacrificed its beauty to benefit others.

I touched Wilde’s right shoe and let my hand rest on its gleam. A streaky rasher of a man ordered me to step aside so he could snap photos. I remained, claiming my time, and at my leisure moved to the two stone pillars opposite. A bronze sculpture crowned each one, the first of Wilde’s pregnant wife, Constance, and the second the torso of the Greek god Dionysus. Wilde’s quotes, written in gold ink, adorned the base of the pillars. I told myself that the first quote my eyes landed on would be a signpost. I was ready for a new life chapter – had been ever since my divorce four years earlier. The ache, the restlessness, had turned manic now that my third son was headed for college in August, leaving me alone in our three-bedroom brownstone in Chicago’s South Side, the last house in the cul-de-sac. I read the first Wilde quote my eyes found, a quip about breakfast that offered me nothing.

We soon came to accept, even embrace, Mary’s presence. Her appearance cracked open Da’s years-long depression, an abyss we’d lost hope of anyone, anything, ever penetrating.”

Along Clare Street, in the window of a brightly lit art gallery, a black-and-white photograph of Seamus Heaney also pulled. Heaney, wearing silver-rimmed glasses and a dark Aran jumper, sat reading a book, its title blurred. I recalled his poem about peeling potatoes with his mother, less the lines themselves and more how they made me feel. Of all his work that I’d read, that domestic poem pressed.

The Oscar Wilde Memorial Sculpture by Danny Osborne in Merrion Square, Dublin. Spleodrach/Wikimedia Commons

Da’s ravings and Mary’s arrival had alarmed my family – I could never forget that shivery eeriness on first seeing through the hallucinatory eyes of a madman – but we soon came to accept, even embrace, Mary’s presence. Her appearance cracked open Da’s years-long depression, an abyss we’d lost hope of anyone, anything, ever penetrating.

A man spoke up next to me, his voice flamboyant, commanding. “I declare dripping, not dipping, the superior word.”

“Sorry?” I said, turning my head. I felt only a moment’s startlement, and then a knowing calm. Clearly, the theme of the day was conjuring, and if I was going to call forth anyone, why not the great Oscar Wilde. No bland Marys for me, thanks very much.

“The knives,” Oscar said impatiently.

I silently recited the line in question from Heaney’s poem twice, testing both words. “Either works,” I said. But ‘dipping knives’ was undoubtedly the better choice.

“Well don’t dally,” Wilde said, moving off in the direction of his alma mater.

—

Inside Hodges Figgis, Wilde located his books. I traced a red-brown spine with reverence, my finger pausing on Portrait. “What’s that like, after all this time?”

“I expected nothing less,” he said.

Inside Carluccio’s, he drank espresso and spoke fluent Italian, his eyes darting to everyone but me. Mary had served Da so much better, in the beginning at least. The whole scene put me in mind of my marriage – how Ben and I had taken each other for granted all those years. How invisible we became to one another.

Wilde scribbled on a paper napkin. He was sizable, flabbing. Just as with Ben, I couldn’t decide what stopped him from being all-out handsome. The hooded eyes, I posited. His hawkish air. It certainly wasn’t his flagrant lips. He demanded more napkins. So many napkins, a white wall of words rose between us.

He wrote through three pens, until his right hand cramped, and next his left. I hadn’t known he was ambidextrous. Then he napped. He snored, farted. I thought about my siblings and the old friends I’d put off seeing. Instead, I was enduring this. Still in the grip of jet lag, sleep also tried to claim me.

Wilde’s shouting roused me with a start. His stacks of writing had vanished. I tried to magick his story back to the table, but couldn’t. His rage turned to grief. I tried to console him, but again failed. He charged from the cafe. I hurried alongside him down Dawson Street and suggested we see a play. Over breakfast, I’d read a rave review for The Lieutenant of Inishmore. We could catch the matinee.

Wilde paused on Grafton Street to read a young man’s cardboard sign, its bottom edge serrated. If ten people give me two euro I’ll have enough to get a bed tonight.

When I first immigrated to Chicago, I couldn’t believe the amount of homeless on the streets and the depths of their wretchedness. More, I couldn’t comprehend how people blindly walked past them. All too soon, I had also turned numb. Now there were more and more homeless on the streets of Dublin and its crowds milled past, ignoring, normalising.

“Tragic,” Wilde said of the sign with contempt.

“May I?” I said to the young man, fishing a pen from my backpack. I turned the ripped cardboard over and demanded Wilde dictate. Once, I was you. Someday, you could be me. The young man’s dirty fingers scrabbled at Wilde’s words, as if trying to lift them off the cardboard. I saw a flash of him as a child, touching snow for the first time.

“What’s your name?” I asked.

“Richie,” he said, and laughed. “I’m thinking of changing it.”

“Hiya, Richie,” I said, handing him a twenty. “Please use it for shelter.”

He promised, and thanked me, his head bowing repeatedly to a beat only he could hear.

“He’s absolutely going to buy drugs, or at least drink. I know I would,” Wilde said.

Inside the Gaiety, the green stage curtains parted. Wilde issued a startling sound twinning agony and euphoria. Throughout the performance, he repeatedly shouted “Bollocks,” alternatively angry, contemptuous, impressed, aroused.

As we exited the theatre, he muttered, “Even at the best of times cats are a perversion.”

On the walk back to the guesthouse, he stopped in front of his childhood home and placed his hand over his heart. Inside the park, in front of his monument, he adjusted his stiff penis.

Inside the pizzeria on Upper Grand Canal Street, we shared bruschetta and a beetroot salad with goat cheese and pomegranate seeds, the latter an act of God.

“He doesn’t exist,” Wilde said. “Spoiler, sorry.”

We lamented the vinegary red wine. He said, “Wit, that’s the only place tart belongs.”

He demanded port and tiramisu. I wanted to get back to the guesthouse, and safety. Da and Mary had gotten along great until they started going outside together. They went from drinking themselves happy in pubs to falling down drunk on streets, to disappearing for days, to getting into altercations. I insisted Wilde skip dessert.

In my bedroom, I changed into flannel pyjamas and messaged my three sons in our group chat. My eldest, James, responded first. Hope you’re having fun. I played Tina Turner from my phone. My youngest, Danny, sent a thumbs up emoji. The middle child, PJ, might not respond for days. Wilde and I danced to “What’s Love Got to Do With It.”

He breathlessly declared, “You’re going up in my estimation.”

I shouted above the music. “Tell me the best is yet to come.”

“The best is yet to come,” he roared.

Mary had only obeyed Da for so long. I was determined to remain queen of Wilde. We danced, my subject and I. How we danced. In bed, he folded himself against my back and locked his arm around my waist. I slept. How I slept.

I was alone. Yet I felt a presence. Those long-ago skin-crawling sensations returned, during Da’s first sightings of Mary and on realising how wide his mind had split.”

In the morning, Wilde’s side of the bed was empty. I remembered I’d started a higher dose of my antidepressant and wasn’t supposed to drink alcohol, but the floaty effects were spectacular. I likely had that, the lingering haze of my sleeping tablets, and my twisted imagination to thank for Wilde’s guest appearance. PJ messaged me back. Take photos. It was almost 4 a.m. in Brooklyn. You okay? I typed. I waited, but he didn’t respond. Once more, sleep closed in.

In the early afternoon, I walked to my hair appointment. Along the way, I discovered St Mary’s church and felt compelled to enter. God or no God, I’d always loved churches – their stillness and sacredness. The thrum of hope.

I deposited every coin in my possession into one of several padlocked moneyboxes and burned an entire row of candles below St Anthony, patron saint for the recovery of lost things.

“Thief!”

I turned around, expecting to find Wilde, but I was alone. Yet I felt a presence. Those long-ago skin-crawling sensations returned, during Da’s first sightings of Mary and on realising how wide his mind had split. He and I would get into shouting matches. Me saying Mary wasn’t real, and him calling me a thief, trying to steal Mary from him. I rushed out to the street and into the cold, sharp air.

I arrived to the hair salon flustered and teary. The receptionist checked me in, her entire face smiling and her deep African accent powerful. She offered to take my jacket.

“I was mugged,” I blurted.

“Jesus. When?”

“Just now, on the way here.”

She rushed out from behind the reception desk and touched the top of my arm. “Are you okay?”

“I’ll be fine, thank you.” The relief of the lie was already fading and guilt was swooping in.

“Take a seat,” she said, leading me to a white pleather chair.

“Would you like tea? Black, green, mint, or chamomile?”

How far Ireland had come in the twenty-seven years since I’d left. “Mint, thank you.”

She returned with the steaming mug of tea. “Would you like to reschedule your appointment? Because that would be no problem.”

“I’m fine, really.”

She moved behind me and spoke to my reflection in the mirror. “Just straight and sleek, yeah?” she said, placing her hands on my shoulders. My skin prickled, sending a fresh crawling sensation up my neck and over my scalp. I couldn’t remember the last time anyone’s touch had made me tingle.

She led me to the washbasin, my shoulders missing her warmth. Her head massage proved horribly weak. Maybe she felt the need to go gentle on me. I wanted to be worked on.

We returned to her station and she combed through my hair, tugging on the knots. “Did you get a good look at him?”

“What?”

“The mugger?”

“It was a woman.” The lies had an appetite of their own.

“No way. Did she take much?”

“About a hundred euro.” I had committed to the fallacy and couldn’t stop.

“A hundred euro? Jesus, that’s awful, that is. She’ll have no luck.”

Several times she said it. She’ll have no luck.

My phone pinged, a reply from PJ. I’m good. Why? I was relieved, and annoyed. “Why?”

“Are you at least going somewhere nice tonight?”

“No plans, really,” I said, prolific now in deceit. She didn’t need to know that I was meeting my siblings and their spouses for dinner.

The ordeal ended. I followed her back to the reception desk. “I’d love to not have to charge you,” she said apologetically.

“That’s okay, thanks,” I said, pulling a roll of cash from my jeans pocket.

“Oh,” she said, surprised.

I realised I should have used my credit card. I mumbled an excuse, only “after” and “ATM” clearly audible. Her eyes narrowed.

Parched and famished, I hauled myself out of the guesthouse – freshly convinced I was a lot of things, including lonely and an attention-seeker, but I wasn’t mad.”

At dinner, inside the trendy, candlelit restaurant on Dame Street, we totalled a party of seven – my younger sister and her husband, my two older brothers and their wives, and me. Within minutes of meeting, we appeared entirely caught up. My gaze slyly tracked our waiter. When I finally caught his attention, I signalled for another rum and Coke. My sister looked down the table at me, concerned, questioning. In energetic, deflecting detail, I told them about the play at the Gaiety and afterward the delicious Italian dinner.

“You went alone?” my sister said.

“Yes,” I said, only it felt like another lie.

I pushed away thoughts of the hair salon and continued drinking, no longer caring if they judged me. The imperative was to douse my dishonesty, and the fear of inheritance.

Most of the next day, anxiety and a ringing hangover pinned me to the bed. Finally, parched and famished, I hauled myself out of the guesthouse – freshly convinced I was a lot of things, including lonely and an attention-seeker, but I wasn’t mad. I struggled over the now familiar streets of Ballsbridge, feeling wholly tender, as if my body had been beaten black and blue. A walking haematoma. The first time I heard that word, I was fifteen. The doctor was describing the massive bruise on Da’s hip after falling down our stairs. Da claimed Ma had pushed him, his voice turning shrill with fright and paranoia. The police interviewed Ma, my siblings and me. Next, the psychiatrist took her turn with us. Ma reluctantly signed the papers, committing Da to Grangegorman. His stay lasted months, and when he returned home Mary was gone. As I passed the Grand Canal Hotel, I could still hear him wailing for her.

I continued on aimlessly, chancing unfamiliar streets in search of something beyond hydration and food. Arriving at the docklands, I stopped short at the edge of the plaza, stunned by the glittering waterway, state-of-the-art glass theatre, and the revamped red-brick and cast-iron warehouses. For a fog-brained moment, I thought I was back in Chicago’s financial district. I followed the savoury drift from a large, fancy-looking supermarket named fresh. At the expansive meal counter, I eyed the roasted meats and vegetables, mounds of stuffing and mashed potatoes, and trays of thick gravy and sauces. Overwhelmed, I moved to the soup and salad buffet, then to the shop’s deli, butchers, bakery, and aisle after aisle of tantalising foods, wanting so much and taking nothing.

I paused at the supermarket’s cafe and the rows of brightly coloured doughnuts behind spotless glass. I could be standing inside Firecakes Donuts in Lincoln Park. There was a time when there was a world of difference between Ireland and America, but with each passing year, I saw more of the sameness creeping in. It was tempting to think I could resettle here, but the craggy island dredged up too much for me to stay permanently. I returned to the soups and ladled my fill. Homemade, the sign promised.

In the last days of Da’s life, Mary returned. “I thought I’d killed her,” he told me through the phone, his voice carrying from Dublin to Chicago. “She says she’s sorry.”

“For what?”

“She hurt a lot of people.”

I was still trying to work up to something when he said, “Would you forgive her?”

“That’s up to you,” I said, wondering if he was asking something else. I’ve often questioned, since, if he somehow knew that would be our last conversation.

Each man kills the thing he loves. It was a Wilde quote I expected to see on one of those pillars inside the park, but it was excluded. Perhaps I wasn’t the only one who didn’t understand it. I rushed the chicken noodle soup inside me, tasting mercy, and yet again wondered what Wilde had loved and killed. Maybe it was God. Maybe that’s why Wilde said He didn’t exist. Regardless, it was wrong of him to implicate everyone in the same murderous act. It seemed far more true that we kill parts inside those we should love the most, ourselves included.

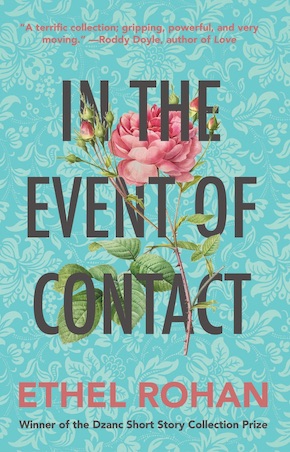

From the collection In the Event of Contact (Dzanc Books, £12.99)

Ethel Rohan’s debut novel The Weight of Him (Atlantic Books, 2017) was an Amazon, Bustle, KOBO and San Francisco Chronicle Best Book, and was shortlisted for the Reading Women Award. She is also the author of the story collections Goodnight Nobody and Cut Through the Bone, the former longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize and the latter longlisted for the Story Prize. Her work has appeared widely, including The New York Times, World Literature Today, The Washington Post, PEN America, The Irish Times, Tin House and The Stinging Fly. Raised in Dublin, she lives in San Francisco. In the Event of Contact, winner of the Dzanc Books Short Story Collection Prize, is out now in paperback.

Ethel Rohan’s debut novel The Weight of Him (Atlantic Books, 2017) was an Amazon, Bustle, KOBO and San Francisco Chronicle Best Book, and was shortlisted for the Reading Women Award. She is also the author of the story collections Goodnight Nobody and Cut Through the Bone, the former longlisted for the Edge Hill Prize and the latter longlisted for the Story Prize. Her work has appeared widely, including The New York Times, World Literature Today, The Washington Post, PEN America, The Irish Times, Tin House and The Stinging Fly. Raised in Dublin, she lives in San Francisco. In the Event of Contact, winner of the Dzanc Books Short Story Collection Prize, is out now in paperback.

dzancbooks.org

ethelrohan.com

@ethelrohan

@dzancbooks

Buy from bookshop.org

Author portrait © Justin Yee