William Ryan: Seeking answers to the darkness

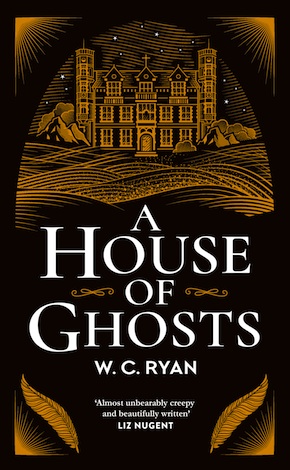

by Karin SalvalaggioWilliam Ryan’s historical thriller A House of Ghosts has been receiving high praise in the press and from readers. I’m willing to bet the stunning cover design, featuring an embossed gold-leaf image of Blackwater Abbey, has played a part in the novel’s success. Stars flicker in the night sky and stylised rays of light fan out from the corners. Little design touches, such as the Art Nouveau motifs that line the spine and the pitch-perfect use of historical typefaces, hark back to the golden age of crime fiction. The former graphic designer in me couldn’t resist picking it up when I first spied it in a bookstore. A few pages in and the reader in me couldn’t resist bringing it home. The writing, like the cover, is beautiful yet understated.

I originally met William at First Monday Crime, a monthly event held at City, University of London that he helps organise. In November, we found ourselves on the same flight to Iceland Noir, a twice-yearly crime fiction convention held in Reykjavik. I caught up with him back in London.

KS: The blurb on the inside cover beautifully illustrates A House of Ghosts’ overriding theme: “As the First World War enters its most brutal phase, back home in England everyone is seeking answers to the darkness that has seeped into their lives.” Without giving too much away, could you please summarise the plot further?

WR: This is trickier than you would first think because there’s a lot going on. I suppose firstly, it’s a country house murder mystery – in that the novel is set in a country house on an island (which has, of course, been cut off by a storm), to which a disparate group of individuals have been invited by the arms manufacturer Lord Highmount. While there isn’t a murder at the beginning of the novel, there is an attempted murder that leaves its victim in a coma. The two central characters, Kate Cartwright, a codebreaker, and Captain Robert Donovan, an Irish engineer who is happy to deal summarily with the king’s secret enemies as long as it avoids his return to the trenches, are amongst the guests tasked with catching a German spy, which I suppose makes it an espionage novel of sorts. And then there are the ghosts, a lot of them, which gives it a supernatural element. And finally, there’s the romance that develops between Kate and Donovan. There’s sadness – the purpose of the weekend on the island is the attempt contact the dead soldier sons of the attendees via a series of seances – but there is also a lot of fun.

I was particularly taken with the evolving relationship between Donovan, who thinks he’s seen it all, and Kate, who is about to prove him wrong. Could you comment on the inspiration behind their partnership? Will we be seeing more of them in future?

I certainly hope so. The ending is a little ambiguous as regards their romance and I’ve been told by several readers, in no uncertain terms, that they expect a sequel and a more definitive outcome.

I read a lot of Agatha Christie in my youth and like many readers, can’t help but find parallels with And Then There Were None – the isolated mansion, the growing threat, and an upper-class cast of characters, many of whom have something to hide. We as writers are free to write about anything, be it the future, the past or the present. A House of Ghosts is set in a particularly brutal phase of the First World War. What was it about this era that inspired you? Did you set out to juxtapose the reality of conflict with the rigid social mores of the British upper classes?

I decided quite early on that if I was going to write a novel set at the tail end of the First World War, I’d like to make it feel like a novel from the period, but with perhaps a more modern viewpoint.”

I suppose I also read a lot of Christie when I was younger and certainly a lot of the country house conventions found their way into A House of Ghosts but the plot, aside from the location, bears very little resemblance to And Then There Were None. Christie used Burgh Island in South Devon as the basis for the setting of And Then There Were None and coincidentally, I used to live a couple of miles away from there, so I would say the island, in altered form, was an inspiration for both of us. If I ever read Christie’s novel before writing A House of Ghosts, and I’m not sure I did, it was so long ago that I have no specific memory of it. But other novels, like Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, as well as similar mysteries by Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh and the like were definitely an influence. There are also other elements as well – Eric Ambler and John Buchan had something to offer the spy story and Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances certainly shaped the relationship between Kate and Donovan. And fans of M.R. James and Daphne du Maurier might recognise some of the ghostly elements. I think I decided quite early on that if I was going to write a novel set at the tail end of the First World War, I’d like to make it feel like a novel from the period, more or less, but with perhaps a more modern viewpoint.

Though the tone, setting and content is purely historical, A House of Ghosts never feels like a pastiche. You very cleverly subvert the usual tropes through the use of social commentary. Could you comment on the inclusion of references to gender inequality, social inequality, PTSD, the Easter Rising, pacifism, profiteering in the arms industry, and the increasing mechanisation of modern warfare, that has little patience for human frailty?

I always have lots of things I want to think about in a novel, which often means exploring different perceptions of an historical development. Donovan, like many Irishmen, would have started the war fighting for the rights of small nations and believing his service might provide an avenue to Home Rule, as many Irishmen did. The Easter Rising changed many Irish soldiers’ perception of the war. It’s not that I wanted to make a big deal of it, but he makes clear that his loyalty is transactional, rather than heartfelt – and I suspect many British soldiers felt the same way by 1917. There is so much social change happening in and around the First World War – votes for women, socialism, and the loss of faith in established ruling structures – that it’s hard not to make mention of some of them. I had a lot of fun writing the novel, and I think it’s fun to read, but the First World War was a cataclysmic event and that’s difficult to ignore.

The expectations of class are illustrated perfectly when Donovan pretends to be a manservant and unintentionally attracts the romantic interest of Molly, a young woman in service to the household. Though disappointed when the subterfuge is exposed, Molly is by no means crushed because the rules are clear: Donovan is a gentleman and therefore out of her league. There are many examples of this rigid social dynamic played out in literature, television and film. Why do you suppose writers turn to it again and again?

I think because it’s interesting – they’re both human beings and attracted to each other, but they don’t exist in isolation. Donovan and Kate, because of their social status and relative financial wellbeing, have far more freedom than Molly does. Molly, being a sensible woman, recognises that while she could possibly have a fling with Donovan it would likely end quickly and possibly not very well, for her at least. Donovan can book a train ticket to London tomorrow and know where he’s going – Molly simply can’t. But if they were marooned on a desert island where they’re on a more equal basis, then who knows what might happen. Kate and Donovan can embark on a relationship without fear of the consequences – Molly can’t.

Arthur Conan Doyle, who lost his son early on in the war, was a firm believer in spiritualism, and there were many others, at every level of society. It makes sense when you consider how many died.”

Almost 750,000 British troops died in combat in the First World War. The families and villagers in A House of Ghosts are mourning the loss of entire generations of men. The casualties were often missing presumed dead, their bodies never recovered. In such circumstances, it’s hardly surprising that surviving family members would turn to spirit mediums to contact the dead. How prevalent was the belief in ghosts during this era, and was it commonplace for people to turn to the aid of spiritualists?

It was very common. Arthur Conan Doyle, who lost his son early on in the war, was a firm believer in spiritualism, and there were many others, at every level of society. It makes sense when you consider how many died, as a proportion of the men of military age, and look at the names on village war memorials and see the same family names repeated several times. One of the things I wanted to recreate was the shock that must have been to the people at home, when the country had not been involved in a serious military conflict for a hundred years beforehand. It’s something we should remember whenever we become complacent about the world order we find ourselves in currently.

A character named Dr Reid has an interesting theory. He proposes that the multiple concussions suffered by troops under constant bombardment can make them less likely to pass over to the other side when they die on the battlefield. He has a patient, Private Simms, who is able to communicate with dead soldiers after being given a drug that was developed to lessen the effects of shell shock, or PTSD. It is a theory that sounds far-fetched enough to be real. Was this an actual theory you came across in your research or did you make it up?

I don’t think many people believed that concussion had an effect on the ability of spirits to cross over to the afterlife, but they did believe some strange things. My fictional theory is probably based on the knowledge that concussion can have very surprising effects on the brains of the living, and that more than nine in ten deaths in the trenches were due to artillery fire. I think I did read something along these lines.

And finally, could you tell us what you’re working on now?

I’m wondering how revealing I can be about this, given it’s only half-written, but it’s another historical crime novel which mixes genres. It might be a little scarier than A House of Ghosts, or it might not be. There’s definitely an icebreaker involved.

William Ryan is the author of five novels, including the Captain Korolev series set in 1930s Moscow, which have been shortlisted for numerous awards, including the Irish Fiction Award, the Theakstons Crime Novel of the Year, the Endeavour Historical Gold Crown and the Crime Writer Association’s Steel, Historical and New Blood Daggers. He lives in London with his wife and son and is a licensed mudlarker and keen cyclist. A House of Ghosts is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Zaffre.

William Ryan is the author of five novels, including the Captain Korolev series set in 1930s Moscow, which have been shortlisted for numerous awards, including the Irish Fiction Award, the Theakstons Crime Novel of the Year, the Endeavour Historical Gold Crown and the Crime Writer Association’s Steel, Historical and New Blood Daggers. He lives in London with his wife and son and is a licensed mudlarker and keen cyclist. A House of Ghosts is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Zaffre.

Read more

william-ryan.com

@WilliamRyan_

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala