Write what you don’t know

by Justin Courter

By the time I wrote Cadenza, I had realised that the advice to ‘write what you know’ was lousy advice for a fiction writer. Part of my artistic agenda was to do something like the opposite. Writing what you know is a good way to stop your imagination before it even gets started. It’s also what I did when I wrote my first novel, which was semi-autobiographical. I didn’t try to get it published because I could see its amateurishness very soon after I finished it. Around that time, I read either an interview or an essay in which John Updike said that he had written a practice novel before writing the first one he published. That helped me see my own effort – which I was thinking of as completely wasted – as something perhaps important to my development as a writer, and definitely more palatable than outright failure. It had simply been a few hundred pages of practice.

When writing fiction, you are going to draw on what you know anyway, consciously or unconsciously, especially when striving for verisimilitude and emotional resonance. And if ‘what you know’ is being used in the imagined world of a novel or short story, the process of employing it is more like method acting. You have to imagine your way into a different context using pieces of your own experiences, emotions, knowledge, etc. I had come to understand this better by the time I had the idea for Cadenza, which was a number of years, and a lot more writing, after my practice novel. Instead of writing about what I knew, I did research on subjects and people I knew nothing about. Not only was this much more interesting, but it fed my creativity; astonishing things I read about were continually suggesting themselves as subject matter and influencing the direction of the narrative taking shape in my mind.

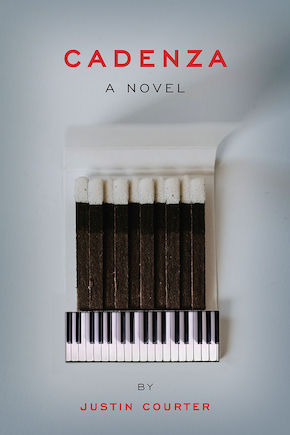

Cadenza is a realist novel that tells a somewhat sensational but not completely implausible story. A girl named Jennifer from a low-income, blue-collar background is severely burned in a house fire (miraculously, her hands are not harmed) and goes on to become a world-famous classical concert pianist and a composer. Jennifer’s life story was pretty remote from what I ‘knew’ as a man with no traumatic, disfiguring experience in my childhood, and ignorant about the lives of burn victims, pianists and composers. To inhabit Jennifer’s character, I went to the library and read a lot of books about burn victims, pianists and composers. This might sound like I was doing homework – essentially I was, but that was not how it felt. It was more like being on an expedition that kept my imagination working. Everything I read was potential material that could be used in what I was constructing.

Writing what you know is a good way to stop your imagination before it even gets started.”

It wasn’t until I was probably halfway into my first draft that I realised part of the reason I had decided to make Jennifer a burn victim was an experience from a few years earlier. I had worked in the medical division of Little, Brown & Company as a proofreader. Among the books I’d proofread, there had been a few about reconstructive surgery for burn victims. The images in these books were extremely disturbing. I made big changes in my life after I left that job – including travelling a lot and living in different parts of the US – which is the only excuse I have for not having realised, until I was already well into the writing of Cadenza, why I had chosen this form of physical disfigurement for my main character.

I suppose what I felt for the burn victims I saw in photographs when I was working as a proofreader was pity; what I hope I achieved a few years later when I wrote Cadenza was empathy. For whatever reason, those photographs had made a lasting impression on me, importantly, as something I did not ‘know’, i.e. what it was like to live with those kinds of scars. And that was part of the imaginative exercise involved in writing Cadenza. A lot of what drives Jennifer to excel as a pianist is a reaction to what happened to her as a child. It is a way of coping. Jennifer survives the fire but her sister dies, so she lives with tremendous guilt and with severe disfigurement. The disfigurement results in a partial exile from normal life, but Jennifer’s drive, her relentless determination to overcome anything in her way, and eventually her fame, set her even further apart from other people. I wanted to explore all this on an emotional level, and to explore ideas about art and creativity on an intellectual level.

Variations on the approach I took to writing Cadenza have continued to work for me. I might have an idea for a story, maybe a character or two, and then I start reading non-fiction on subjects that are relevant to the story or the characters’ lives, and I read fiction that is related in some way to what I want to write. It seems to me that research can never hurt. Even if you decide not to use it, you’ll learn something, and if you keep going, reading with an eye toward storytelling, jotting notes and ideas along the way, you might come across things you can use, or a story might even start to grow out of the research. And you might even choose a subject seemingly at random when really you’re unconsciously drawing on some other past experience. So, if like me you don’t want to write what you know, you can always write what you want to explore.

—

Justin Courter is the author of the novels Skunk: A Love Story and The Heart of It All, and a collection of prose poems, The Death of the Poem and Other Paragraphs. He writes reviews of independently published books for the American Book Review, Rain Taxi and other publications, and his short stories, prose poems and humour pieces have appeared in Pleiades, The Literary Review, The Berkeley Fiction Review, McSweeney’s and elsewhere. He lives in Queens, New York. Cadenza is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

justincourter.com

@owlcanyonpress