Time to say goodbye

by Justin Courter

Most people live in compromise. For me, this has never been an option. Not that I ever wanted some insipid “normal” existence, but people have said, and I suppose will always say, she did this or that “because of the accident” or “in spite of the accident.” These statements amount to the same thing: they’re wrong. I was Jennifer Coleman before what I did that slightly famous night when I was seven years old. And what I did was no accident.

Since my opus will be published posthumously and no one besides Felix, who’s dead, knew I’d been composing these last nineteen years, I feel obligated to do some kind of explaining. But I don’t really believe in explanations. So that’s not right. I’m writing this all down mainly to get things straight in my own mind. What I am is the music and the music speaks for itself. For anyone who’s interested enough, this can accompany the music. This piece can be my accompanist.

Most people have accompanists their whole lives. This is what I mean by compromise. You play tennis because it’s something you can do with your spouse, when maybe you’d rather be reading a novel. You become a stockbroker or a saleswoman because it’s a sensible way to support yourself and your family, when maybe you’d rather be painting or trekking in the Himalayas. I was able to see this frustrating and sometimes stultifying dilemma at an early age and resolved never to let it become my reality. The clarity of my vision, more than anything else, determined the course of my life. What happened to me in the fire only helped to anneal my will.

I’m a Promethean. This is something my parents were unable to recognize. Not many people did. No one expects the most hideous girl in the neighborhood to become the greatest classical pianist the country ever produced. My parents come to mind first because I just put them on a plane a couple of hours ago. Now I’m sitting in my tiny dining room, an interlude between the kitchen and the living area, with the stacks of sheet music piled up next to me, ready to send off to Ernest, my ex-manager. It’s Sunday, it’s just gotten dark, and rain is drumming the roof.

Sunday evenings have always seemed melancholy to me, even though I’ve never had to go to a job on Monday morning. My calling is not something I have the luxury to come home from. I live in it as if it were my house, eat with it as if it were a fork, sleep with it as if it were my lover. The music never stops playing, seeping in and spilling out of me, changing in color, tone, and shape. I just try to keep up with it, really. I have pens and paper in the kitchen, on the bedside table, and in my car, so I can make a note to change something on a score. I spend almost all my time within reach of my piano, so I can sit down and iron out a phrase that’s not working right. Wrong notes find their way into almost every piece at one point or another.

Maybe this Sunday evening melancholy goes back to my early childhood when the end of the weekend meant the end of being able to practice uninterrupted for the entire day. In elementary school, I had to cut class and sneak into the music room to use the piano. That thing was so horrendously out of tune I had to ignore the sound it made and listen to the sound in my head, the sound I knew it should have made. The upright my parents had was a piece of junk, but at least they had it tuned regularly. I saw to that.

My calling is not something I have the luxury to come home from. I live in it as if it were my house, eat with it as if it were a fork, sleep with it as if it were my lover. The music never stops playing.”

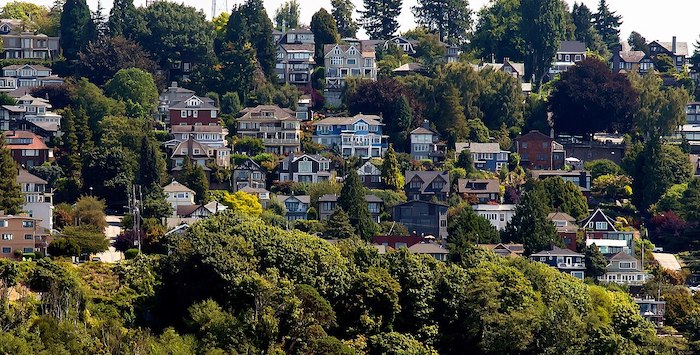

I’ve lived in this bungalow on Queen Anne Hill for six years. The living room is big enough for my concert grand, the table beside it on which I compose, and not much else, which is just fine. Which, in fact, is why I chose it. I do not need large, distracting spaces. This space reminds me of the practice room I used at Juilliard, except it has a bay window through which I have a view of the shifting mural of clouds that come tumbling in from the Pacific like dirty rags, pile up at the Cascades, and wring themselves over Seattle. In the foreground of this picture is my throw rug of a yard, a tangle of roses, and the ship canal at the bottom of the hill.

It’s been a year since I re-established contact with my parents and until this weekend, we’d only spoken on the phone. About a month ago, Betty called me in the middle of the afternoon because she was trying to find my address in her road atlas.

“Now, Jenny dear, you’re in Queen Anne?” she said. I’ve never liked being called anything but Jennifer since I could speak. “That’s just south of Fremont, right?”

Betty is a busy little woman whose bunchy body and staccato style of comportment always reminded me of an ant. I’m nothing like her. I have my father’s long, fence-post limbs and more deliberate mannerisms. I suppose calling me Jenny was a way for her to reclaim me, and such a petty way, that I was willing to make the concession – the first step toward the compromise their visit would represent – a first and a last.

“Right,” I said. I wished I’d left the phone off the hook as I usually do when I’m composing. Betty, a wrong number, or some jackass telemarketer can break into the middle of the symphony in my head and destroy my concentration for an hour or more. But since Betty had me now, I thought this might be as good a time as any to invite her and Ron for a visit. I wanted an opportunity to say goodbye to them. The invitation wouldn’t be easy though. I’d never asked them for anything. I hadn’t seen them for seven years and didn’t really want to see them at all. They would only make me sad and, I knew, have second thoughts.

“Queen Anne. That’s such a nice name,” Betty said. “I always think of lace and then I think of you sitting on a doily on the top of a hill. I can’t find Gilman Street here. Wait, they have this pullout thing that’s more detailed.” I heard paper crinkling. “I see Burke-Gilman. That’s not it, is it?”

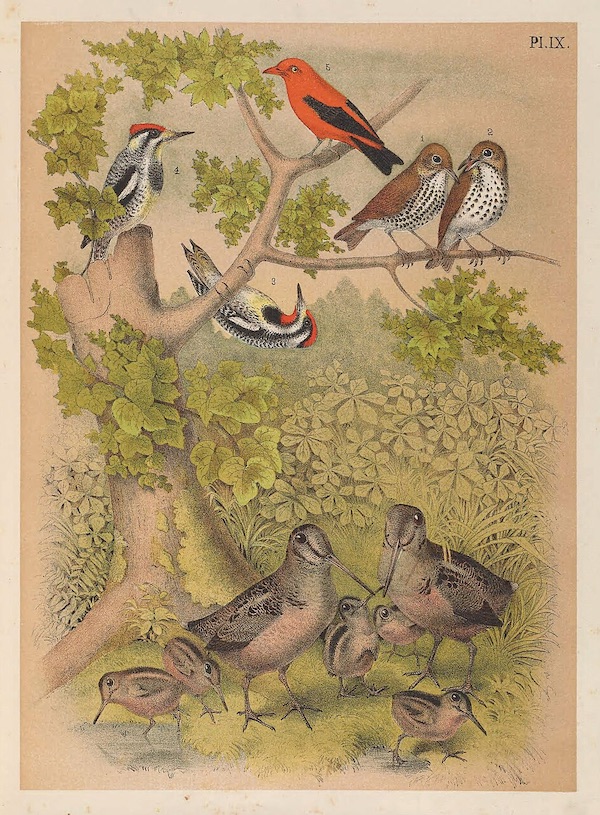

“That’s a bike trail,” I said. I shook a cigarette out from the pack by the phone and lit it. I pictured my mother worrying over her atlas with the phone tucked against her shoulder while my father – oblivious, snug in his recliner, encircled in a halo of lamp light – thumbed through seed catalogs or the Birds of North America field guide.

Betty and Ron are extremely provincial. Ever since I gave them the money to move from our depressing hometown of Malden to a house in Sudbury, forty minutes west, they’ve behaved as if they’d been transplanted to the middle of the Congo. And though they’re fascinated by the exotic flora and fauna, they are still somewhat scandalized by the social customs. Their neighbors pay more annually for yardwork than Betty and Ron would spend on a car.

I learned to listen, but it was still a couple of years before I truly began to hear, something most musicians never learn.”

“Oh, wait, wait, here it is,” Betty said. “Gilman. Now are you on Gilman Place or Gilman Avenue?”

“Place,” I said, trying not to sound irritated. She hadn’t even asked whether I was busy when she called.

There was silence on the line while Betty ratcheted up the nerve to ask whatever it was she’d called to ask. I’ve learned to hear what’s implied by these silences. Like rests in a piece of music, Betty’s silences mean as much as anything she can say in that moment. There was some frustration rattling behind this particular silence.

Gustav, my teacher at Juilliard, got annoyed with me before I learned how to hear properly. During one of our lessons, he was pacing around agitatedly while I played Bach’s Italian Concerto. Finally, he couldn’t stand it any longer and burst out, “No, no, no! You’re not hearing the music at all. You’re just playing notes. The music is behind the notes.” I learned to listen, but it was still a couple of years before I truly began to hear, something most musicians never learn.

“Will you be coming home for Thanksgiving?” Betty finally blurted.

It was a ridiculous question. I’m thirty-six and I haven’t been home for Thanksgiving since I was twelve. But I didn’t say it was ridiculous because I knew Betty was standing there like a frumpy, miniature Statue of Liberty, her wrinkled lips pursed, the phone held like a lowered torch in one hand and the atlas clutched so tightly in the other that her palm was sweating and sticking to the page.

“I wasn’t planning on it,” I said.

“I didn’t think so.” She gave a short sniff. “Well. We’ve been reading about where you live. It sounds like a beautiful place.” I didn’t respond, but she plowed on, determined to have a positive conversation. “I read about the Olympic Peninsula. Did you know there’s hot springs there? And your father was telling me about the San José Islands. He says they have some special kind of whale there.” Now Betty needed the resident naturalist for backup. “Isn’t that right, Ron?” she said, her voice fading as she turned away from the receiver. A quizzical grunt was sounded somewhere else in the room. “Will you go get on the other phone, it’s your daughter on the line,” Betty said, as if I were the one who’d called them.

I heard the crunch of the recliner’s leather and some other muffled sound, probably a fart. The other phone is in the bedroom. Betty has given me a detailed description of their house and even sent photographs. I know she thinks it’s rude that I’ve never come to see it, but she won’t say so because I paid for it. “Will you pick up that other phone!” Betty yelled.

“I’m here, I’m here,” Ron said. My father is a peaceful man who gives the impression of being perpetually bewildered by the complexity and diversity of the planet. I’m sure he’d be content to tend his garden and identify the birds that visited it while World War III raged all around him.

“What were you saying about whales the other day?” Betty demanded.

“Whales?” Ron asked, as if he’d never heard of them.

“In the San Josés. Where Jenny is.”

“You mean the San Juan Islands?”

“Whatever.”

“Oh. Yeah, well, I was reading my magazine from the Audubon Society. Apparently, there’s a lotta orcas up there.” The crippling Massachusetts accent, by which Rs are pressed into Ahs, is more pronounced in Ron’s voice. He sounds as if he’s being forced to speak while undergoing dental work. The accent makes me feel sorry for Betty and Ron; they sound uneducated, which they are. Not that I sound so wonderful. My voice is permanently scorched.

“Orcas, that’s it. And what else were we talking about?” Betty asked.

Ron sounded like a fifth grader who’d been called on by the teacher. “About Jennifer?” he said.

I don’t know what’s more painful to my ear, “Jenny” or “Jennifah.” But this was, of course, the perfect opportunity for me to invite them to visit. They wouldn’t invite themselves because I’d said no before.

Well, here goes, I thought. I exhaled into the receiver and stubbed out my cigarette.

“Are you smoking?” Betty asked. She’d gotten herself all worked up into a tizzy by now. Between resuscitating the reclining Ron and discovering that my irrelevant fling with these cowboy killers had continued, Betty was on the verge of a fit. And though it was only mid-afternoon here, it was just before their dinner hour, and I remembered how snippety Betty could get when she was hungry.

“Yeah,” I said. “Betty, don’t worry about it.”

I had to steer us back to the subject of location, but the conversation wasn’t going any further unless Betty got out what she wanted to say.”

Another of Betty’s strained silences followed and I realized that – with a single exhalation of smoke – I might have blown my chance to extend an invitation. Betty was torn between an instinct to pick up mothering me where she’d left off when I was twelve and a desire to establish an adult relationship with me on a scrap of extremely shaky ground. I had to steer us back to the subject of location, but the conversation wasn’t going any further unless Betty got out what she wanted to say, which had somehow gotten lodged in her larynx.

“Okay, Betty,” I said. “What?”

She still refused to speak up.

“Betty?” Ron said uncertainly, as if he might, upon returning to the living room, find that she had walked out the front door and left the phone dangling from its cord.

“It’s just—” Betty stopped herself. Her voice wavered when she spoke again. “It’s only that I don’t see the point. Why would you want to move all the way to the other side of the country just to die of smoke inhalation?”

“Betteee,” Ron said, his voice dropping to a baritone on the “e” as if she were a supposedly housebroken dog that had just crapped on the rug.

It was my turn to be silent. None of us had spoken about the fire for at least two decades. No, come to think of it, we had never really talked about it at all.

“I’m sorry,” Betty said. “I didn’t mean it to come out that way. I meant—

Jenny, are you still there?”

“I’m here.”

“Are you planning to start giving concerts again soon? You could move back East again. Everything’s happening in New York. There’s nothing for you out there.”

“Betty, I gave up public performances seven years ago.” Everything’s happening in New York? Since when had she started talking like Ernest?

“I know,” Betty said, her tone suddenly turned from shrill anger to a cloying sweetness. “I know that. Don’t you think I know that? But you could always pick it up again, I’m sure. You didn’t have to drop everything and become a hermit just because of that boy.”

“You know why I quit doing concerts,” I said.

By the silence that followed, Betty meant, “You poor dear.” And I knew the look on her face at that moment. It was the one so many people’s faces assume when they see me. They can go straight to hell. I’m not a poor dear; I’ve made quite a bit of money. And I’m not disabled; I’m disfigured. Everyone has gone through some kind of pain in her life. The scars don’t show on most people.

Actually, Betty does not know why I gave up performing. No one does.

Betty knows the public-relations answer, which is that I wanted to devote myself to recording. And I do prefer to make and listen to recordings rather than live music. The best way to experience music is in solitude. This is the only way it is possible for the musician and the listener to step outside themselves and, together, become the music. There is no possibility of such intimacy and transcendence in a crowded concert hall where everyone is comparing dresses and jawlines, where someone is coughing in the row in front of you, and someone next to you is squirming around, bumping your elbow. I’ve done some recording, but anyone could see that the number of them I’ve produced has not been enough to keep me terribly busy the last seven years.

“Jenny, honey?” Betty said. “You know I’m sorry about what happened to your friend, don’t you?” She never even met him.

“Yes. It’s all right,” I said. “It’s been a long time.”

Indirectly, Felix did have something to do with my giving up public performances.

I would not say that I began composing because of Felix, but he was definitely a catalyst in my metamorphosis from performer to composer. There are some people who muck around in your life for long periods of time – by accident of where you happen to live, work, or go to school – and turn out to be of as little consequence as the furniture around you. Then there are others with whom you spend a small amount of time, but who do infinitely more to influence your life. Your memories of them are more vivid. Felix was an Icarus; I could see that right away. What I couldn’t see, until it was too late, was how much he meant to me. This observation I withheld from myself the way a pyromaniac might keep her matches hidden in a drawer. I had to do this in order to compose. Since the best way to experience music is in solitude, it follows that for the composer, the sublime can only be attained in solitude. The process of shaping and appreciating new melodies becomes simultaneous. This is when the experience is deepest. The performance, for all the moment can and sometimes does achieve, is superficial in comparison. By the time it’s ready for an audience, the composition is already ancient history for the composer; it’s only news for the listener. Though I was dedicated in my early years, I lacked the kind of patience required of a composer. And I knew what I truly wanted but didn’t yet have the courage to seize it. I was gradually becoming aware of all this when I met Felix.

“I didn’t mean to bring that up,” Betty said. “I’m just trying to – I don’t know.”

“I know,” I said. “Well then, why don’t you come out for a visit?”

This completely baffled the little woman. “Really?” she said, the pitch of her voice making a steep, sudden climb right up the scale.

“Really,” I said.

“Oh, Jenny, we’d love to, wouldn’t we, Ron?”

“Sure,” Ron said in a broad croak, then cleared his throat.

When I hung up the phone, I realized extending the invitation had been easier than I’d anticipated. I hoped that saying goodbye, too, would just be a matter of finding the right opening. But I knew it wouldn’t be as easy, because not only would I have to be given the right opportunity, I would have to say goodbye without telling them why I was doing so. Without, in fact, even letting them know that I was saying goodbye. This wouldn’t be the kind of goodbye you delivered in an airport terminal before administering a peck on the cheek and waving them off. What I wanted to effect was a kind of spiritual synchronization for the three of us, even if it only lasted for a moment. I wasn’t sure what words, if any, would be spoken and could not imagine a setting. I felt as if I were acting as my own impresario for a performance where I’d have to improvise, which isn’t what I do. I’ve always had the music before every performance – had it down cold.

When I think over other goodbyes I’ve had to say, the memories melt into a collage of unrelated arrivals and departures. That pretty much sums up the life of a concert pianist. But leaving is the most painful, and pain is what makes us feel most alive.

from Cadenza (Owl Canyon Press, US$24.95)

—

Justin Courter is the author of the novels Skunk: A Love Story and The Heart of It All, and a collection of prose poems, The Death of the Poem and Other Paragraphs. He writes reviews of independently published books for the American Book Review, Rain Taxi and other publications, and his short stories, prose poems and humour pieces have appeared in Pleiades, The Literary Review, The Berkeley Fiction Review, McSweeney’s and elsewhere. He lives in Queens, New York. Cadenza is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

justincourter.com

@owlcanyonpress