The enthusiasms of Zoe Pilger

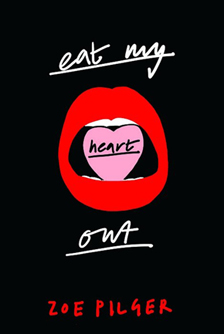

by Lucy Scholes Between her day job as an art critic for the Independent, and completing her PhD on romantic love and sadomasochism in artist Sophie Calle’s work, the multi-talented Zoe Pilger has written Eat My Heart Out, a commanding post-post-feminist satire about modern romance, an anti-romance if you will.

Between her day job as an art critic for the Independent, and completing her PhD on romantic love and sadomasochism in artist Sophie Calle’s work, the multi-talented Zoe Pilger has written Eat My Heart Out, a commanding post-post-feminist satire about modern romance, an anti-romance if you will.

Pilger’s (anti-)heroine is 23-year-old Ann-Marie. She’s just failed her finals at Cambridge, has been dumped by her boyfriend, and is completely broke. Ricocheting from one disaster to another, she’s on a rollercoaster ride through London in search of true love, from baby boomer dinner parties in Islington, Little Mermaid-themed warehouse parties in Hackney, crazy one-night stands, even an appearance on Woman’s Hour (though somewhat forced, and wearing an L.K. Bennett bag on her head). Along the way, she meets legendary feminist Stephanie Haight who immediately take’s Ann-Marie’s re-education in hand, though not, perhaps, with the expected results.

The novel is fast and furious. Reading it is something like a punch in the gut that leaves you gasping for air but the pace is such that you simply can’t stop to get your breath back. It’s sharp, hilarious and sad too; the trip one imagines would be the result of ingesting a packet of love hearts laced with acid. “Not since Martin Amis’s early work,” wrote the Daily Mail’s admiring review, “can I remember a novel so exhilarated – and made so exhilarating – by its own sense of disgust.” And at the heart of it all is the fabulously bonkers figure of Ann-Marie…

LS: Ann-Marie is about as unforgettable a character as they come. Can you tell us a little about her genesis? I think you’ve mentioned elsewhere that she’s something of your alter ego – can you expand on this a bit, where’s the line between the two of you, and is it a fine or a firm one?

ZP: I have come to think of Ann-Marie as my alter ego because she has co-existed with me in changing form over the last six years. I first began to sketch her character in 2008, when I was 23 myself. I wrote the first 20,000 words of a novel called Cover Me with a female protagonist who was obsessed with raw meat and falling in love. She was called Helen.

I was also very interested in the idea of superstition. Ann-Marie looks to the external world for signs that affirm her own wishes. For example, at the beginning of the novel, she believes she sees two swans swimming in perfect symmetry, which she takes as a sign that Vic [the man Ann-Marie meets at the beginning of the novel and believes she’s in love with] will call her. In fact, they are merely two plastic bags, “floating aimlessly across the freezing water.”

I was fascinated by this kind of fatalism, a desire to be validated by a basically supernatural force, against all common sense. This is Ann-Marie’s magical thinking. I see it as a symptom of her disempowerment and related to her position as a female. I’ve done a lot of research into superstition, fatalism, and femininity for my PhD – I’m interested in how women are encouraged by popular culture to believe in a predestined fate, embodied in the form of ‘The One’. This is also related to the fatalistic idea that a man will save you, which discourages you from taking responsibility for your own fate.

That was one aspect of the genesis of Ann-Marie’s character. In regards to how she relates to me – I came to think of writing Ann-Marie’s voice in the first person as similar to acting. I found I could easily go into role as her. Fiction is a space of freedom wherein moral codes don’t apply. Ann-Marie doesn’t give a damn about conventional morality, and that was a lot of fun to write.

Was the story driven by her or vice versa – did you begin with the character or the concept?

The novel began as a short story about a bad one-night stand, which remains the first chapter, although it has been rewritten since. Ann-Marie’s voice and the story came to me at the same time – I think they are inseparable. Her view of the world was the motor of the narrative because I wanted the novel to be ‘picaresque’ (although I only realised the form had a name very recently, after I’d finished writing the book). I wanted the action to be based on her collision with the city and the characters she encounters, with no sense of a preordained plan. I wanted her to react spontaneously, and I wanted to her write her spontaneously. However, the novel went through four drafts so after each rough sketch, I would go back and intensively rewrite/edit, with the help of my editor, Hannah Westland.

Eat My Heart Out also seems to be a novel very much about London. How similar is the London you know to the fictional version you’ve created?

It was pointed out to me recently that it could be read as an “anti-love letter to London”, which I liked a lot. Ann-Marie often expresses hostility to London, but she is immersed in it, she is part of it. I think she loves it, really. I was born in London and have more or less lived here all my life – I love it.

You’ve already been compared to the likes of Lena Dunham and Sheila Heti and thus, by extension, the voice of your generation. How do you feel about this? Do you see your work as similar to theirs – are you a fan of Dunham’s show Girls and/or Heti’s novel How Should a Person Be?

I’m very flattered to be compared to these two women. I think my book has been compared to Girls mainly because of the demographic that it describes. And it’s similar to How Should a Person Be? in the sense that it explores interior female experience and is quite experimental in form at some points. I think both Lena Dunham and Sheila Heti are really talented, and have opened up what contemporary writing by women can be.

However, I think Eat My Heart Out is different in tone – it’s much darker and more surreal. The action is more detached from reality, and there is more direct reference to feminist ideas.

You’ve recently written very eloquently about your relationship with Simone de Beauvoir’s seminal text The Second Sex and how important reading it was to you. Obviously Eat My Heart Out is a work of fiction, but do you also regard it as some kind of politicised statement? Ideally, what would you like (young female) readers to take away from Ann-Marie’s story?

My book is politically committed in the sense that I am a feminist, and I consider Eat My Heart Out to be a feminist book. However, I don’t want the book to have a concrete ‘message’, or to proselytise to its readers in any way. What I love about writing fiction, and what seems to me to be unique to the form, is the freedom to ask questions, even to disarrange the questions, to play with ideas rather than asserting absolutely your position. For me, writing is always a way of working out. That’s what I find exhilarating about it.

Following on from my previous question, it seems that the central relationship in the book is that between Ann-Marie and Stephanie Haight and this says something about the need for strong role models for young women. Who were/are yours and why (other than de Beauvoir, of course)?

Ann-Marie tries to create idols, but they always fail. I like to think that she is going through a long, slow process of realising that it’s not necessarily healthy to idolise anyone, or anything. Idolatry, in this sense, is a form of submission. It’s a way of abdicating from thinking for oneself, and deferring instead to someone, or something else. Ann-Marie is looking for an idol in Stephanie Haight, but she also idolises Vic through distance; she idolises her romantic history with Sebastian [the ex she’s recently broken up with]. In short, I don’t believe in having idols! I prefer the anarchist slogan – “no gods, no masters.”

My PhD research has influenced both my art reviews and Eat My Heart Out. Stephanie Haight’s non-fiction book within the novel is based on a lot of my research, albeit in more deranged form.”

However, there are a lot of people whose work I admire – Angela Carter, Anna Kavan, Jane Bowles, Louise Bourgeois, Paula Rego, Natalie Djurberg. I admire many from the second wave women’s movement of the 60s and 70s. I watched the 1971 documentary Town Bloody Hall recently – it’s a filmed debate between Norman Mailer, Germaine Greer and others – about feminism. Greer makes a stunning speech about the dominance of male genius. And questions from the audience come from Susan Sontag, Cynthia Ozick, Betty Friedan. The documentary is electrifying – there are so many female writers in the room who are committed, diverging, intelligent, funny, frank. A lot of good role models.

Can you explain a little how the various different strings to your bow – your work as an art critic, your PhD and Eat My Heart Out – are connected (if at all)? It seems to me that there must be some kind of relationship between the thinking through of similar questions and concepts in different fields.

All the different types of work that I do relate to one another. My PhD research has influenced both my art reviews and Eat My Heart Out. Stephanie Haight’s non-fiction book within the novel, Falling Out of Fate, is based on a lot of my research, albeit in more deranged form. Also much of my approach to art reviewing and academic research comes from my fiction writing. The imagination necessary to writing fiction is very useful when it comes to considering an artist’s work, or analysing texts. I am very lucky that I enjoy all of my work a lot, and these overlaps and connections happen quite naturally.

Fiction-wise, are you working on anything new now? Any chance we’re going to encounter Ann-Marie again, Isadora Wing-style, as she continues her adventures later in life?

Haha! I did think about doing a Rabbit series with Ann-Marie – checking in every decade or so to see how she was doing. I’d like to know what she was up to aged 33. But I’m not sure if I’ll go ahead with that. I’ve just started writing the third chapter of my next novel, which is about a romance writer who gets locked in a mental asylum for pushing against the bounds of the genre. And I’m planning a non-fiction non-academic book based on my PhD research on romantic love, sadomasochistic power relations and femininity. I also would like to write a monograph on Sophie Calle at some point.

Eat My Heart Out is published by Serpent’s Tail.

Read more

Lucy Scholes is contributing editor at Bookanista and a literary critic and book reviewer for publications including the Daily Beast, the Independent, the Observer and the TLS. She also teaches courses at Tate Modern and Tate Britain.

Follow Lucy on Twitter: @LucyScholes