“Don’t kill me, I beg you. This is my tree.”

by Hassan BlasimHe woke up and , before the last vestiges of the nightmare faded, made up his mind. He’d take him out to the forest and finish the matter off. Fifteen years ago, before he’d shot him, he’d heard him say, “Don’t kill me, I beg you. This is my tree.” Those words had stayed with him all that time and would maybe stay with him forever.

Karima made breakfast for him. She had a black scarf on her head and eyes as still as a tree by night in spring. Absentmindedly, the Tiger slowly drank water from his glass. He took his time to set the glass down on the table and then stared at it.

“Now the water’s inside me,” he said, “and you’re empty, you fucking empty glass!”

The Tiger spoke to everything around him in this way, as if he were acting in a play. These conversations took place internally. No one else heard them – or else the Tiger couldn’t have kept his job as a bus driver, his source of income and the way he helped himself forget. The Tiger would often glare at the television screen and, regardless of what was on, give it a piece of his mind: “You whore, selling and buying your mother’s arse!”

Karima would go and sit in the living room with her fingers on the buttons of the remote control, switching channels as if she were playing a nonsensical tune on it. She settled on an Iraqi station: an announcer in garish make-up smiled as she introduced a traditional Iraqi song about maternal devotion. Karima shed a tear at the first Ah from the well-known rustic singer. The Tiger walked past and, without turning towards her, went into his room. He opened the wardrobe and put on his bus driver’s uniform. From the shelf he pulled out a pistol wrapped in a piece of cloth and tucked it under his belt. He left without even saying goodbye to Karima, his wife and companion of twenty-four years. Many years ago he had given up looking into those eyes, which had enchanted him and wrenched his soul in his youth. In those days, the Tiger’s claws dripped with blood from the brutal water wars, and Karima’s radiant eyes suggested deep reserves of love.

The Tiger worked the night shift, but today he left home early. His eyes were severe, as if he were on a serious mission. He went into the Hemingway café, ordered a coffee and sat down at the fruit machine. He played and won. He lost and played again. In the end he lost forty euros. He threw a contemptuous glance at the fruit machine and left the café. It had started to snow heavily. The Tiger gazed at the snow.

“You know, if you were in your right mind, you wouldn’t shit in the bowl you eat from,” he told it – in just the kind of tone you’d expect of a kid from a neighbourhood run by pill poppers and brutal police. The Tiger called it the ‘Cowards’ District’; he’d had the energy and callousness to commit any crime he wanted to without falling into the hands of the police. That’s why they had awarded the crown of ‘Tiger’ to young Said Radwan. They gave him the title and cheered him off to the water wars.

The Tiger felt an overwhelming desire to write, but he didn’t dare, and deep down inside he still thought it impossible to turn the images of horror in his mind into words.”

The Tiger headed to the public library and spent some time there before work. He seethed with anger as he looked for a new crime novel, and addressed the row of books on the shelf. “I know you’ve jumped out at me from nowhere, but I know how to fix you up good and proper, you fat rotten bastard. You lousy novel,” he said.

He pulled a novel from the shelf and sat down to read.

His passion for crime stories had begun when he started living in Finland. That was before he joined the bus-driving course. The Tiger felt an overwhelming desire to write, but he didn’t dare, and deep down inside he still thought it impossible to turn the images of horror in his mind into words. Sometimes he would spit out the names of the writers on the covers of the books in one of his inner dialogues: “You geniuses, sisters of whores, authors of blood and violence everywhere in the Cowards’ District, in the water wars and on paper. My God, curse the father of the world you live in.”

The Tiger left the library to smoke a cigarette outside. He watched the snow falling but didn’t talk to it. He went back to the reading room, set sail with the crime novel and drowned in it. The time soon passed. The Tiger’s skin suddenly shivered and he looked at his watch. He put the crime novel back in its place, borrowed another one and left.

The Tiger’s fingers gripped the steering wheel tight as he drove the number 55 bus through Helsinki’s icy streets. A stream of images and memories ran like a trail of ants through his blood, down from his head and ended up crowded and swarming in the tips of his fingers. He looked at his face in the rear-view mirror. His skin was as dark as rye bread, flecked with a sparse white beard. Who would have thought the Tiger would ever become so frail and wizened?

The bus halted at a stop close to the Opera House. He turned to the building and gave it a sigh: “Sing, sing. Farid al-Atrash used to sing, and say that life was beautiful if only we could understand it. Well, you can lick my arse.”

The Tiger looked for his quarry, the fat man, in the mirror above his head. No sign of him among the passengers. The fat man hadn’t appeared for more than two days. But he’s bound to turn up at the last stop, the Tiger thought to himself as he fingered the pistol in his belt. He closed the bus doors and stepped on the gas, cutting a path though the continuing blizzard.

It was more than a month ago now since this new passenger had started riding the bus: a fat man with Iraqi features. The Tiger had never managed to work out how he got on the bus. Passengers were supposed to board through the front door, but the fat man didn’t. The Tiger kept his eyes on his mirror – a constant vigil for the fat man sneaking on via the rear doors – which was a strain on his nerves. The fat man was like a ghost: he would appear on the bus and then disappear, until eventually they came face to face and the strange man revealed his identity.

Apart from the fat man appearing on his bus, the Tiger’s life went on at the same depressing rhythm, as he struggled with his family and himself. For the last three years his son Mustafa, who was now twenty, hadn’t been in touch with him or his mother. The kid had rebelled early against the Tiger’s cruel treatment, and now sold marijuana and lived in a small flat with his Russian girlfriend.

His wife Karima – “the woman with the stunning eyes”, as those around her used to call her in the old days – was lost in her own world, mentally and physically detached from her husband. The Tiger felt she was punishing him for the years of bitterness she’d spent with him. Karima spoke for hours on Skype with her brothers in Baghdad, sharing their joys and their sorrows. She would laugh and cry on Skype, yearning for the past and bemoaning her luck. There was nothing left of Karima, the young cheerful English teacher: with the old Finnish woman next door, her only friend, she’d go through photographs from when she was an elegant young woman with stunning eyes. When the old woman died, Karima’s pictures died too, because there were no longer eyes to grieve over the shadows of the past with her.

The Tiger showed no interest in Karima’s isolation, because he too had turned in on himself, focusing on his bus, and his conversations and the fruit machine. His only remaining consolation after work was to meet up with a hard-drinking Moroccan friend in some bar. His friend would always talk about the difference between Finnish and French women, or between Spanish and Arab women. He knew the stories of all the regulars in the bar and gave each one a nickname. When the Moroccan had his own business to attend to, the Tiger would sit in front of the fruit machine and throw away his money.

As far as the Tiger was concerned, it was obvious from the start that the strange man was targeting him with his appearances and disappearances on the bus, even before he managed to confront him about it. On that occasion the fat man was sitting in the back seats. The Tiger went up to him and told him in Finnish that this was the last stop. The fat man smiled and stared at the Tiger’s face.

Switching to Arabic, the Tiger asked him, “Are you Iraqi?”

The fat man took some chewing gum out of his pocket and began to chew as he answered: “Don’t kill me, I beg you. This is my tree.”

The words struck a powerful chord in the Tiger’s mind. He stepped back a few paces, then took one confused step forward towards the man. They were the same words he’d heard years ago in the pomegranate orchard.

“What is it you want?” the Tiger asked.

“Nothing,” the fat man replied.

The Tiger had a good look at the man’s face.

“Did you used to work with the water gangs?” he asked.

“No, but you killed me.”

“I killed you! But you’re not dead!”

“How are you so sure I’m not dead?”

***

His wife Karima didn’t know what kind of work he’d been doing in those years. He’d excused his absences by saying he had to travel to other cities to buy and sell used cars. When the police got on his trail, the Tiger and his family fled to Iran, and from there to Turkey, where he applied to the United Nations for refugee status after forging some documents and claiming that he was an opponent of the dictatorial regime then in power. Finally, through the United Nations, he reached Finland.

That night, the night of the pomegranate orchard, the Tiger was driving the car, accompanied by another killer. The mission was to go to a posh house in the pomegranate orchards on the outskirts of Baghdad. The owner of the house was a boss in a gang that controlled a small river that flowed in from a neighbouring country. The gang owned special tankers for carrying water, which they would sell in areas hit by drought. The government had lost control, overwhelmed by problems: rebels, groups of religious extremists and then the drought, which disrupted a bureaucracy that was already corrupt. The government started bartering oil for water from neighbouring countries. Most of the gangs that had been dealing in arms and counterfeit banknotes expanded their operations and started trading water. Some of them controlled wells and began to impose taxes on the farmers. The mission of the Tiger and his companion was clear: to eliminate everyone in the posh house in the pomegranate orchards. There was intense rivalry between the gangs to win control of the water market. The Tiger and his companion crept through the fence into the grounds of the posh house. They burst into the building, where there were five men sitting at a table, eating and talking. The Tiger and his companion killed everyone in the room. Then he rushed into the kitchen while his companion started looking for some documents in another room. The Tiger found a servant girl cowering in the corner of the kitchen. At the far side of the room there was an open window. He realized that someone else had been in the kitchen and had escaped. He caught sight of the man’s shadow heading deep into the orchards. The Tiger killed the servant girl, jumped out of the window and started running after the man who had escaped. The Tiger was soon out of breath; he couldn’t see the man, but could hear him stepping on dry twigs somewhere. There wasn’t much time. After running some distance further in the pitch black, the Tiger pulled back some branches and found a man kneeling close to the base of a pomegranate tree. The Tiger couldn’t make out the man’s features. He heard him saying that it was his tree and begging him not to kill him. The Tiger aimed his pistol and fired several shots.

***

Once, when the fat man spoke to him, he’d made a strange request: that the Tiger take him for a drive around a forest by night – it didn’t matter which particular forest.”

The Tiger gave a bus ticket to a drunk, turning his face away because the man’s clothes smelled so rank. He looked for the fat man, but couldn’t see him. He spat out one of his rants at the road in front of him: “Roads… roads… all the roads we have walked, when the world is done for. Where are you, fatty? Where are you? Do you think the Tiger’s frightened? A tiger who’s seen all the roads, afraid of a sheep!”

He hadn’t prepared a specific plan for getting rid of the fat man. All he’d decided was that he’d bury him and rid himself of the ghost of his shitty past forever. Once, when the fat man spoke to him, he’d made a strange request: that the Tiger take him for a drive around a forest by night – it didn’t matter which particular forest. At first, the Tiger tried to ignore this man’s weird and foolish words, but his appearances and disappearances so unnerved the Tiger that he asked his Moroccan friend to get him the pistol.

The Tiger drove the bus back and forth along his route. His shift was due to finish at two o’clock in the morning. The fat man appeared, just before midnight, at the bus stop close to the public swimming pool. The Tiger kept a close watch on him, in case this ghost disappeared again.

The last passengers got off at the final stop. When the fat man tried to alight, the Tiger closed all the doors and moved off quickly, changing course. The fat man laughed and asked, “What are you doing, man?”

The bus’s absence would soon be discovered. It was a stupid, reckless act by an ageing tiger; there was only an hour before the bus had to be back in the depot. But the Tiger was in another world. His anger blinded him and paralysed his thinking.

From the back of the bus, the fat man shouted out in derision: “Are you going to kidnap a dead man? Well, if we’re going to the forest, then fine.”

The Tiger didn’t really answer, just threw him one of his rants. “Dead, alive, it’s all the same. I’m dead and alive. You’re alive and dead. So what? Do you think you’re a scarecrow and I’m a crow? It’s amazing, these questions of the dead and the living. They don’t repent and they never learn… Today I’m going to teach you!”

The bus crossed the main road towards the dirt track that led to the forest. The man moved up and sat close to the Tiger. He rambled on about various subjects – the past, coincidence, water, war and peace. The fat man said that over the past years he’d not only been interested in looking for the Tiger but also in piecing together the events that led to his murder. He said he’d often spoken to others about his death. The fat man put a cigarette in his mouth but didn’t light it. Then he took it out of his lips and started to tell the Tiger his story:

“That night I was driving my old Volkswagen, with a little pomegranate tree in the back of the car. The branches were sticking out of the window and the cool night breeze was refreshing. My only daughter had leukaemia and we’d been taking her from one hospital to another. But her condition was deteriorating as time passed. I tried getting blessings from holy men, and when I despaired of them I went to fortune-tellers and magicians. An old woman well known for her psychic powers told me to plant a pomegranate tree in an orchard where pomegranates already grow, and that I should do this at night, without telling anyone. ‘Give life its fruit so that it will give you its fruits,’ the old woman said.

“‘And why a pomegranate?’ I asked her.

“‘Every one of us is also something else – a pomegranate, a flower or some other living thing. He who knows how to move between himself and his other lives will have the doors of serenity and well-being opened for him,’ the old woman answered.

“‘Excuse me, but why can’t it be an orange tree or a grape vine?’ I asked her.

“‘Oranges cure nightmares and grapes are for treating grief, whereas the pomegranate is the pure blood of your daughter,’ the old woman said, and then asked me to leave.

“I would have liked to ask her some more questions, but the psychic said that too many questions undermined the power of mystery. I didn’t understand what she meant. I was thinking about the requirement that I plant the tree by night and in secret. I was desperate, and willing to do anything that might improve the health of the flower of my life, my only daughter.

“I drove there by night. I parked the car and took out the pomegranate tree and a spade. I cut the barbed wire and went deep into the orchard. I chose a suitable place. While I was digging, I heard gunshots. I didn’t pay much attention because the farmers in those parts used rifles every now and then. It might have been a wedding. I was kneeling next to the tree and levelling the soil when you suddenly appeared between the trees and aimed your pistol at me. It was pitch black. But you opened fire and killed me. Why?”

The Tiger didn’t believe the fat man’s story. That night, he’d chased and killed a member of the water gangs. Yes, it was true that the wretch had begged for mercy and said something about his tree. But the Tiger hadn’t seen his face in the dark, so why should he believe it was the fat man? Confused, the Tiger summoned up his courage once more. He had only one thing in mind: getting rid of this ghost of the past that had risen up from underground. The Tiger held his tongue for the rest of the journey.

Inside the forest he stopped the bus, waved his pistol in the fat man’s face and forced him out. He was inclined to stick the barrel in the fat man’s back there and then, but he was frightened of doing so. Could he really shoot a ghost?

The fat man made fun of him. “You’ve already killed me, man,” he said. “What are you doing?” Then he made a run for it.

The Tiger opened fire, but the fat man didn’t fall. He was running like an athletic young man. The Tiger chased him between the trees and in the darkness a shiver ran across his skin and he felt that he was back in the pomegranate orchard that night, as if the fat man, the bus, the snow, his son and Finland were just a waking dream in his head, as if he were still there, a strong Tiger, hunting down his victims in the vicious water wars, without hesitation.

Through the open window the Tiger caught sight of a shadow in the orchard. He fired a bullet into the head of the girl in the kitchen. Then he jumped through the window and ran after the shadow of the man who had escaped. He heard the sound of footsteps breaking dry twigs. Then he caught sight of another man sitting, levelling the soil around a pomegranate tree. He ran past him and continued to chase the man who had escaped.

The forest came to an end and opened out onto the frozen lake. The Tiger kept chasing him over the icy surface. Finally the man who had escaped came to a halt. The Tiger came up to him, aiming his pistol at the man’s face. The man from the water gang quickly raised his hand and pointed his own pistol in the Tiger’s face, and shots rang out.

Blood flowed across the icy surface of the lake.

Translated by Jonathan Wright

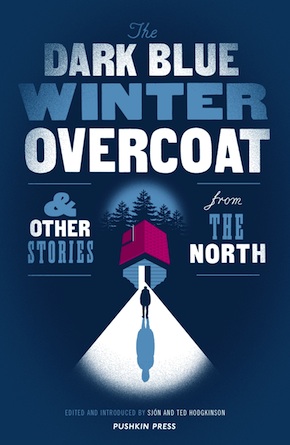

From the anthology The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat, edited and introduced by Sjón and Ted Hodgkinson, published by Pushkin Press in association with Southbank Centre, to coincide with their year-long celebration of Nordic culture, Nordic Matters

Hassan Blasim was born in Baghdad in 1973, where he studied at the city’s Academy of Cinematic Arts. In 1998 he was advised to leave Baghdad, as his documentary critiques of life under Saddam had put him at risk. He fled to Sulaymaniya (Iraqi Kurdistan), where he continued to make films, including the feature-length drama Wounded Camera, under the Kurdish pseudonym Ouazad Osman. In 2004, after years of travelling illegally through Europe as a refugee, he finally settled in Finland. His first story to appear in print was for the Comma Press anthology Madinah (2008), edited by Joumana Haddad, which was followed by two commissioned collections, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009) and The Iraqi Christ (2013) – all translated into English by Jonathan Wright. The latter collection won the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and Hassan’s stories have now been published in over twenty languages.

Hassan Blasim was born in Baghdad in 1973, where he studied at the city’s Academy of Cinematic Arts. In 1998 he was advised to leave Baghdad, as his documentary critiques of life under Saddam had put him at risk. He fled to Sulaymaniya (Iraqi Kurdistan), where he continued to make films, including the feature-length drama Wounded Camera, under the Kurdish pseudonym Ouazad Osman. In 2004, after years of travelling illegally through Europe as a refugee, he finally settled in Finland. His first story to appear in print was for the Comma Press anthology Madinah (2008), edited by Joumana Haddad, which was followed by two commissioned collections, The Madman of Freedom Square (2009) and The Iraqi Christ (2013) – all translated into English by Jonathan Wright. The latter collection won the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, and Hassan’s stories have now been published in over twenty languages.

Read more

Author portrait © Bengt Oberger

Jonathan Wright worked for thirty years as a journalist, mostly in the Middle East, before turning to literary translation in 2008. He has since translated a dozen novels and other major works from the Arabic, winning the 2013 Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation for Youssef Ziedan’s Azazeel and the 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for his translation of Hassan Blasim’s The Iraqi Christ.

The Dark Blue Winter Overcoat collects together the very best fiction from across the Nordic region, including stories and novel extracts from notable authors and exciting new discoveries Naja Marie Aidt (Denmark), Per Olov Enquist (Sweden), Dorthe Nors (Denmark), Linda Boström Knausgaard (Sweden), Madame Nielsen (Denmark), Rosa Liksom (Finland), Johan Bargum (Finland), Kristín Ómarsdóttir (Iceland), Kjell Askildsen (Norway), Ulla-Lena Lundberg (Finland/Sweden), Hassan Blasim (Finland/Iraq), Sørine Steenholdt (Greenland), Guðbergur Bergsson (Iceland), Sólrún Michelsen (Faroe Islands/Denmark), Frode Grytten (Norway), Carl Jóhan Jensen (Faroe Islands), Niviaq Korneliussen (Greenland) and Sigbjørn Skåden (Sápmi/Norway).

Read more