On the matter of eternity

by Mika Provata-CarloneThe past few years have seen the explosive emergence of a highly fetishised and merchandised cult of the home: as a fiercely protected private space of explicitly public (voyeuristic) visibility, as the locus of a redefined, globalised community of purported ecumenical camaraderie, as the shrine of high-design spirituality, and as a new status symbol of belonging and power. From the campy idolising of pluralist kitsch and liberalist clutter, to the exclusionary dialectics and triumphalism of ultra-high-net-worth minimalism, the concept of the home, as well as the object and commodity of concept homes, have been at the centre of our aesthetic, existential, ideological, socio-political and brass-tack economic pursuits. With the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic and global lockdown measures, the tensions between inner and outer space, between habitation and confinement, or even between reality and facade, or the social politics of a scenography of publicised intimacy, have become even more accentuated. Cabin fever or hermit indulgence? Bubble cosmographies or cellular existence? Art brut backgrounds or perfectly curated virtual wallpapers?

Beyond the frustration or the business opportunity, and as a ramification of the sense of isolation and the fear of unsettledness, or the unhoped-for prospect of a sabbatical from the vagaries of ‘normal’ pre-pandemic existence, lies a question of essence and substance. Namely a question of what sustains us and what grounds us – what fulfils the precepts of “what a piece of work is man” and provides the earthly space, the material reality, the place of both solid being and intangible transcendence. Redeeming the simple (vital) centrality of the home may well be one of the most radical gestures of both action and resistance that we can perform at this point in time, and an unsuspected bright side to the multiple fronts of darkness looming right before our eyes.

Rather than leaf through interior decor manuals, or vademecums of hygge, zen or feng shui, a rather more thrilling proposition is to explore the past stories of homes and human dwellings, to trace the history of conscious belonging to and in space, to piece together the various narratives of human agency (or lack of it) in defining one’s very world. Such a chronicle of presence and now absence would be a testament and a litmus test of humanity’s permanence or transience: of the ways that those who lived before us, in the same homes, or in buildings which, though vanished, remain somehow geographical palimpsests of being and nothingness, defined with brick and mortar, aesthetic vision and utilitarian objects, the terms and the quality of our relating to ourselves, to others, and to what lies beyond, to time past, present and future.

The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy, the product of a lively and clearly relished intellectual collaboration between Abigail Brundin, Deborah Howard and Mary Laven, each a scholar in a different field of historical research, promises such an engrossing journey through time and states of being and belonging. It prides itself for its quietly measured, yet boldly radical positions, its innovative perspectives, its determination to make us look at the Renaissance both within and outside the home with new eyes free of ideological constructs, historical stereotypes or revisionist agendas. It tells its story patiently and absorbingly, with a delight in detail and a fine instinct for pearl-fishing, bolstered by a profound enchantment with Italy, impressive scholarship, a talent for wonder and observation, and a keen interest in developing a new understanding of the spiritual value, function and social agency of the Italian home across classes or regions through a dynamic engagement with theoretical analysis. Even at a time when we are becoming increasingly aware of the organic significance of interdisciplinarity, one cannot also fail to attest a concurrent opposition to a more vitally relational appreciation of our world, whether in the sciences or the humanities, in private or public life. The Sacred Home is a staunch response to this hostility towards the ethics of true dialectical interpretation, a book that celebrates the instinctive naturalness of looking over and beyond one’s own intellectual garden patch, or what the authors call “boundary hopping”, of striking real or imagined conversations with other people, other times, different ideas, customs, perceptions of mortal and immortal existence.

Even though the authors do not name it explicitly, their book seeks to redress the balance of influence and power between secular Humanism and a sacred perception of the world.”

The very term Renaissance is a much polemicised or contested one, implying a necessary breach, a rebellious unshackling, and a moving away from a previous state of essentially comatose cultural and social existence. The authors offer a reflected response to the narratives of Jacob Burckhardt, Pompeo Molmenti and Attilio Schiaparelli, who muted the dimensions of the sacred in the Renaissance in favour of a now supreme, as they claimed, rationalism, pragmatism and progress, which retrospectively predicated the Middle Ages that preceded it as being dark, oppressive and regressive. “In these vintage studies, the Italian casa was quietly enlisted in the secularising narrative of the Renaissance.” Individualism and individual space became the typical representations of the new age of ‘reason’ that vanquishes the ‘obscurantism’ of faith. The Sacred Home begs to differ: it counters “the remarkably enduring stereotype of the Renaissance as a ‘secular age’ and instead embraces the less familiar concept of ‘Renaissance religion’.” It challenges the foundation myth of the Renaissance as merely a “rebirth of classical culture and therefore [as placing] non-Christian values at its heart” and, even though the authors do not name it explicitly, their book seeks to redress the balance of influence and power between secular Humanism and a sacred (in this case Christian Catholic) perception of the world. Their ‘reclaimed’ period of the Renaissance spans from 1450, the year Johannes Gutenberg begins printing a Bible using movable type in Mainz, to 1600, when Giordano Bruno is burnt at the stake in Rome, when the first Dutch ship arrives in Japan, and when Galileo’s daughter Maria Celeste is born. They offer a highly textured panorama of what Margo Todd called “Christian humanism”, and their critical background is the simple and ordinary Italian home, as well as the more sumptuous and dazzling palazzi of the period.

The Sacred Home defines itself as a study of “the ways in which people experienced domestic devotion” or an exploration of the intimate side of faith, rather than an examination of the public structures and hierarchies of the official church and state. It tells, both authoritatively and beguilingly, a very personal story of belief in everyday life, of the private relationship between the Italian people and their God, saints and angels. The story is told by finding the words to express the ineffable symbolism of everyday objects, rituals and interior spaces; by rendering palpable their intangibility, and their crucial role in defining and enabling private and social existence and relating. Material culture, and material wealth culture in particular, are often the focus of Renaissance studies, whether through the histories of collecting, of transcultural influences or cultural confluences, or through an annalistic survey of social progress through the evolution of materiality and material conditions as evinced in inventories and archives. What has received less attention is the “fact that the multiplication of ‘worldly goods’ was matched by an explosion of devotional commodities, from images of the Virgin Mary and prayer books, to pilgrim souvenirs and rosaries… The ‘consumer revolution’ of the Renaissance… played a key role in the domestication of religion.”

The Renaissance is not simply a ‘progressive’ phenomenon. It is a fervent counter-stance to the emerging Reformation and the latter’s reaction to the dogma and praxis of the Catholic Church; it is unquestionably also a response to the rediscovery of antiquity, particularly through the influx of manuscripts and their bearers from Byzantium, through spolia brought back by merchants and Crusaders, or through a new valorisation of sites and ruins on the Italian peninsula itself. It is, by extension, a conscious act of reaffirming a distinct identity, both cultural and religious, through a deliberately interactive and syncretic material culture (an example of which are the famous ‘crusader icons’), even more so, perhaps, once “the Ottoman menace became even more alarming” following the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The religious humanism of Byzantium is an underlying theme, as is the sense of continuity (rather than rupture) that the Greek texts and the Greek scholars brought with them – as has been shown, for example, by Otto Demus. The status of these cultural exchanges, or the symbolism of objects whose provenance had a particular historical context, is illustrated with striking poignancy in paintings such as for instance Francesco Botticini’s Young Man Holding a Medallion depicting a Byzantine saint, or in the visible influence of iconographical and narratological techniques on artists such as Jacobello del Fiore.

The Renaissance is not simply a ‘progressive’ phenomenon. It is a fervent counter-stance to the emerging Reformation and the latter’s reaction to the dogma and praxis of the Catholic Church.”

The secessionist forces of Protestantism had considerable subversive potential: the Reformation challenged not merely the authority of the Catholic Church, but especially the very materiality of transubstantiation, the tangibility of the ineffable achieved by a sacred architecture and aesthetics, by a palpable and objective intimacy with the transcendent. A 1524 painting depicting the burning of religious images and effigies in a church in Zurich cannot disguise in its serene pastel palette, or the tranquil distances maintained by the figures it depicts, the sheer violence and violation that it represents: a man on a ladder is unhinging from a wall the life-size statue of a saint, like a soldier defeating an enemy in physical combat on the ramparts of a castle; a figure in a baptismal font is lying on the floor; three other men with three-cornered hats carry smaller statues in their arms, as though infants or young children, which they will throw in a blazing pyre already devouring a crowd of startlingly (shockingly) lifelike male and female saints. It is a holocaustic image, deliberate and totalising, a highly polished companion piece to the more bluntly partisan pictorial manifesto by Lucas Cranach the Elder, The Difference Between the True Religion of Christ and the False Idolatrous Teaching of the Antichrist, in its Principal Features (i.e. between reformation and Catholicism).

The Sacred Home places the tension between the Reformation and traditional Catholicism centre stage, arguing that the change towards a ratiocentric universe is not necessarily the primum mobile of the period. In this the authors follow John Arnold: “the problem with established narratives of change is that they ‘slip too easily into teleology’; they already ‘know the “end” of the story, and this dictates ‘the unfolding of all that proceeds’.” Protestantism, as the authors show, appropriated the notion of domestic devotion to promote its own religious views, something that has largely been ignored by scholars, as has the place of the home in Catholic religious practice in the early modern period. “The twin historiographies of Renaissance and Reformation have conspired to divert attention from the holy households in Italy” – and beyond.

The Sacred Home tells this untold history or muted story. It does so by identifying and exploring dedicated spaces “from the bedside to the threshold”, practices such as “praying, reading, interacting with images”, objects and stories, notably miracle books and votive images.

This is an exceptionally lucid historical survey of Italy and the complexities of its (unquestioned) sense of national identity, with deliberate focus on off-kilter regions, namely Le Marche, a region that bore deeply the stamp of the Goths, Byzantium and the Francs, Veneto, which equally brought together East and West, and Naples, where Greek and Roman elements of antiquity had now merged with a wealth of ethnic and religious minorities. The sense of coherence versus otherness is inherent, as in the case of Marin Sanudo, a book collector and a friend of Aldus Manutius, whose writings are a source for life in the region of Veneto. Sanudo was also instrumental in placing the Jews of Venice in one of the first gated (segregated) communities. The authors show the inherent rifts within Italy itself between Catholic and Protestant forces, as well as the way art remained, somehow, a relative neutral ground throughout these times – Andrea Palladio was shrewdly and notoriously able to secure rich patrons from both sides of the divide.

The Sacred Home is an ethno-sociological analysis of the history of human relations to inhabited space, aesthetics, geo-socio-politics, and sacred cultural history. From Vitruvius to Mary Douglas, to Gaston Bachelard, Georges Didi-Huberman and Frances Yates, the authors offer a theoretical framework of the art and the realities of living in Italy during that time. They set or question the premises of cohabitation and communal living and the role of devotional life in our understanding of living space, of life in a space that is material, practical and secular as well as transcendental, contemplative and spiritual. The home is not an inward-looking space but rather a crossroads, a platform for encounters and engagement. “The facade of the house creates a permeable and ambiguous membrane between private and public space”, an ambiguity that emerges as being infinitely fecund and even liberating. A strong inspiration throughout is Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space, but also, one suspects, Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, as well as Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. As a result, the voice and tone are meticulously precise, and strong in academic scholarship, yet alluringly poetical and evocative. Each chapter is a philosophical as well as a historical essay, and that is a key part of the book’s appeal and beauty.

Architectural space is revealed to be throbbing with possibility, personality, agency and an enhanced degree of performativity and theatricality. Icons or religious objects would be veiled to protect them from the less exalted aspects of everyday life, unveiled “during prayer to reveal – and thereby activate – the subject of the image, as if to release the presence of the Virgin, or Christ, or a Saint in the room. [They thus] created [and enacted] a moment of revelation.” The explicit and intrinsic female agency in the definition of domestic space is shown to be a gesture of deliberate authority rather than a state of delimitation, whereas devotion, embedded organically in private and domestic life, in the arts, or in the gestures of social connecting at every level and for all, stands in stark contrast to the normative instruction through special manuals, which was the more recognisable practice of Protestantism. In the Italian home, an inner instinct and necessity are created, which translate into a domestic space that is vested with religious significance and purpose, with the intention of enhancing its very domesticity, personalised intimacy and communally shared individuality. Material ownership of the sacred in this context became also a material incarnation of the spiritual.

The classlessness of such a devotional space, and the distinct absence of social, educational or economic prerequisites for its materialisation and inherent value is one of the more remarkable conclusions of The Sacred Home. There is an intense humanity in the facilitating of access to devotional spirituality, to a truly meaningful private existence, no matter the materialistic circumstances. There is no doubt that the transposition of devotional praxis from church to home also came with the potential of a regimentation of daily life, or of a surveillance of private actions and loyalties as regards accepted and expected group ideologies. We know this from trial records, which address everything from idolatry to witchcraft and heresy. There is also a clear opportunity to control the freedom of private time, space, agency. Yet the trade-off was also the transformation of the solipsistic ‘I’ into a communal human being. Especially for women, silent prayer, reading, aesthetically creating and curating the devotional space, constituted essential radical steps towards autonomy, authority, visibility, it defined domains and jurisdictions of their own. They could be (and were) actors, auctors, authors on a par with men.

Literacy and the home, literacy and devotion receive equal attention to spatial architecture, art and material culture, and this is a particularly engrossing storyline.”

Houses were not ephemeral; they had shared and transferable timelessness, either through inheritance or as bequests to servants, clergy, communal institutions. Belonging and possession acquired both a material as well as a transcendental value. Homes also invite what Andrew Pickering has called within the framework of material culture “the dance of agency”, through their connectability and mobility, through the networks and choreographies of belonging that they author and create. Literacy and the home, literacy and devotion receive equal attention to spatial architecture, art and material culture, and this is a particularly engrossing storyline in The Sacred Home. The questions of who could ‘read’, how, what and why, lead to a portrayal of Renaissance society that is often lost, a ‘victim’ of our bedazzlement with the more recognisable material features or intellectual achievements of the time. Literacy ranged from “comprehension literacy”, i.e. full and competent understanding of texts, to “phonetic literacy”, which indicated lexical recognition, the possibility of memorisation, but not necessarily semantic processing or conceptual elaboration of meaning. “We must assume that a level of ‘phonetic literacy’ was available to a very wide sector of society, regardless of their level of formal education.” This meant that memorable passages, mottos, simple and clear messages could be transmitted and assimilated with distinct effectiveness – a proposition with equally positive and negative potential, namely of a sense of belonging, or of easy indoctrination. One cannot but extend these categories to include a social commentary for our times today: the power of ‘headline’ or ‘bitesize knowledge’ politics is reliant on precisely such a division between true comprehension and rote familiarity with information or messages. It (inevitably) follows that the marked current hostility towards culture and reflected learning, towards engaged and trained intelligence, derives precisely from this purposeful privileging of mere message recognition and mechanical memorisation over individual agency in the critical analysis of meaning. The difference is that the Renaissance was creating a path towards such an understanding, rather than away from it…

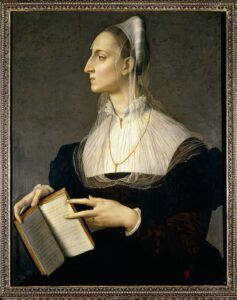

Possession of books held a promise of revelation and participation even when the content was inaccessible due to illiteracy. Possession also meant endorsement, which opened the way to religious persecution and prosecution. ‘Unreadable’ books could imply weakness (inability to read) or power, as in witchcraft manuals, where garbled texts concealed inexpressible potential for control. Illiteracy was also a different kind of asset at the time, suggesting an unadulterated state of purity and guilelessness, an unmediated connection with God. This ‘noble savage’ attitude avant la lettre was based on biblical sources, and was particularly applicable to women, who became vital in “maintaining the spiritual health of a household” precisely through their ‘ignorance’. “From the well-educated scholar in his study, annotating complex works of theology, to the humble artisan who listened to a text while it was read aloud, or the illiterate woman who wore a text that bore significant images close to her body” reading was a vital private and public gesture. Bronzino’s portrait of Laura Battiferi holding out an open book to the viewer and indicating a particular passage with her fingers, to Marietta Robusti’s self-portrait holding a musical score in the same way, to the Paupers’ Bibles (biblia pauperum), which were illustrated simplified publications by the Church that were not dissimilar to the Classics Illustrated series, or the beautifully produced children’s books, all point to the dynamic role enjoyed by “textual communities”, especially in terms of “giving substance to the unknowable”.

Augustine’s theory of the ways in which we engage with or become aware of the sacred consisted of corporeal, spiritual and intellectual seeing, and The Sacred Home exemplifies how there was synergy rather than tension between the three categories, in what the authors call a “delicate balance between the real and the transcendental”. Miracles were another way to embed this, both in terms of experience (which was recorded in special votive tablets or paintings, wax, wooden, silver or metal ex voto offerings, or in handwritten or printed miracle books) as well as in terms of possession and identity. The proliferation of ‘domestic’ miracles was an interesting alternative to the rising cult of the ratiocentric individual: one could single oneself out not by mere intellection, but by referencing and claiming indirect ownership of the miracles that took place in one’s home. Miracle books in particular introduced a new literary genre, which would find, one could claim, rather imaginatively fruitful continuity in the gothic novel. Miracles were a recognisable form of power, and the church was careful to control it, as were the Protestants: “in the early 16th century the culture of the miraculous came under sustained attack from within and without the Catholic Church. Luther, we know, got miracles out of his system when he was a young man” by first claiming two to his own benefit. He was saved twice, once by the Virgin Mary, then by her mother Saint Anne, before changing tack and rejecting them in c. 1515. Erasmus would launch “the most scathing attack” of all, penning a fake letter from the Virgin Mary to Ulrich Zwingli, an unmistakable parody and a rhetorical coup de grâce against the miraculous, anticipating (albeit with reverse intentions) C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters.

Thresholds marked both the limits of mortality and the way to heaven (or hell). From the porta dei morti, which would be often walled up after a person in the household had passed away, to be breached again in order to allow the exit of the next deceased, to entryways with devotional inscriptions, thresholds were vested with pregnant religious symbolism and formed part of rituals of entering or exiting sacred space, community and existence. A particular case was the Holy House (or Flying House) of Loreto, which is said to have been transported all the way from Nazareth to Italy by way of present-day Croatia on the backs of angels.

Rather than inviting insularity, the domestication of devotion cultivated a strong synergy between the formal ‘house’ of faith, the church, and the ordinary homes of the faithful through this common ownership of devotional space and functions. The home in fact domesticated in turn the liturgical space of the church through the integration of votive offerings into the sacred architecture and material narrative of the latter, thus allowing for personal agency and intervention on the part of the common men and women. Tensions of course existed. There was fear that the congregation might slip away from official ecclesiastical authority and credo and into private modes of worship, that the lack of boundaries between secular and sacred space might also bring about the erasure of the distinctions between the sacred and the profane. Yet the domestication of the devotional in both church and home had something tremendous about it, at a time that had its very own pandemics, vicious social conflicts, bloody wars and brutal political upheavals. “For the Tudor linguist John Florio, the verb ‘domesticate’ meant ‘to tame, reclaime, make familiar, mild or gentle’.” The domestication of the sacred implied all of these, especially the determined effort to convert doctrine into feeling, natural gesture, intrinsic human value, a more aware, responsive and responsible social engagement. The Sacred Home traces the patterns of domestication with an unspoken sense of wistfulness: for that home contained the power of meaning, community, fragility, action, interaction and reflection. As, under the cloud of Covid, we near a year of more or less institutionalised domesticity, this is a book that could urge us to ask questions about our own sacred or secular spaces, about what endows our material world (and our very own material existence) with sense, value, purpose and meaningfulness.

Abigail Brundin has written on many aspects of the literature and culture of Renaissance and Early Modern Italy, from female convents to the Grand Tour, and is above all known for her work on the poet Vittoria Colonna, as the translator of Sonnets for Michelangelo (2005) and author of Vittoria Colonna and the Spiritual Poetics of the Italian Reformation (2008). A Fellow of St Catharine’s College, she has taught at the University of Cambridge since 2002 and is currently chair of the Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages.

@Catz_Cambridge

Deborah Howard is an architectural historian whose principal research interests revolve around the art and architecture of Venice and the Veneto. Her books include Venice & the East (2000), Sound & Space in Renaissance Venice (2009, with L. Moretti) and Venice Disputed (2013). She is a Professor Emerita at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of St John’s College. She was elected to the British Academy in 2010.

@DeborahJHoward

Mary Laven has published widely on the social and cultural history of religion. She is the author of Virgins of Venice: Enclosed Lives and Broken Vows in the Renaissance Convent (2002) and Mission to China: Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit Encounter with the East (2011). More recently, her attention has turned to material culture and she has been involved in two major exhibition projects at the Fitzwilliam Museum. She is Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Jesus College.

@MaryLavenCam

The Sacred Home in Renaissance Italy is published by OUP.

Read more

@OUPAcademic

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika