The genius of too much and too little

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“The spider woman, the intellectual, the rebel, the sly enchantress and the good girl sing together in this exuberant, lithe text… I love it.” Siri Hustvedt

“They call them sculptures because they’re made of marble or iron or wood, but they’re really yarns, brief stories from the past that got stuck in your throat, pills that wouldn’t quite go down; you blurt them, mumble them, ruminate over them. And then they show them in Paris.”

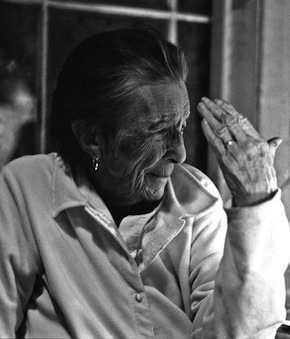

Whether narratives of an inner life, the stark sketches of a private consciousness, the howl of a trauma that deafens with its absolute silence, or staggering, devastating, radically shocking presences one cannot simply override or ignore, Louise Bourgeois’ “messages to the dead that the living intercept” are above all enigmas. Her work, her life, her personality defy all classification, just as they defy unilateral or single-sided reactions to the many, polarised fragments that constitute and destroy her.

Louise Bourgeois the person was surfeit with all the paradox, riddle and charisma of a troubled, suffering humanity that refuses to capitulate even when the only thing left is a frayed, fast disintegrating shred of hope – hope that belonging, love, happiness, life, one’s own consciousness and consciousness generally are possible. Louise Bourgeois the artist evokes the wrenching feeling of awe and the awful, inflicts the greatest dichotomies, pain and almost apocalyptic fear in the viewer, just as she holds us mesmerised, immobilised with her Gorgon’s gaze of a human story full of tragedy we simply cannot afford to ignore.

Jean Frémon, in his novel Now, Now Louison, succeeds in conjuring up not only the persona and the corporeal reality, but also the manic, trailing intangibility of Bourgeois’ voice, the tangled mind and its brilliance. He has said of his story that “everything in the book is imaginary, and yet it is she who speaks, and it is to herself that she speaks.” He calls it a portrait de mémoire, a portrait from memory, and reminds us that “even when we draw the portrait of someone before our eyes, we must still imagine that person in order to recreate them in art… Everything comes from the model,” he assures us, and what a model Bourgeois must have been.

Frémon conjures up a personal vernacular, an incantation of traumas that became a terrible power, the artist’s relentless, unconquerable force of both creation and ruin.”

Her photographic portraits show that she relished the opportunity of posing, of self-representation, of self-mythologising, of auto-fiction, but also of seeing herself the object of another’s gaze and desire, even when she provoked with an almost wicked sense of audacity the most visceral disquietude. Like her archetypal arachnids, she was both ruthless and infinitely protective and generous; a destroyer and a life-giver; the harshest critic and the most inspiring mentor; fragile and omnipotent; a child with the wisdom of a sage beyond time or age. Like her art, Louise Bourgeois the private individual is prolifically displayed, readily available and yet mystical, unknowable, forbiddingly arcane and revelatory at the same time. What makes her unique is the incontestable genuineness of her ambiguity, the absence of all sophistry or games that indulge in dissimulation, the stardom of a narcissistic contradiction. We have her work; we know her biography; we can even feel in the most tactile manner the relief and angularity of her discourse, as well as its rare quality of immediacy, compassion, the unyielding invitation to humanity that it invariably extends.

Bourgeois wrote and spoke, her words can be read and have been transcribed, like ancient oracles, irresistible in their allure and promised wisdom, indecipherable in their poignancy and darkness. From Mâkhi Xenakis’ Louise Bourgeois: l’aveugle conduisant l’aveugle and Louise, sauvez-moi! to Bourgeois’ own commentaries on her work or diary fragments and entries, we have her reverberating, unsilenceable voice. It is a voice that is both torrential and elliptical, governed by an almost extreme sense of order and logic, as well as being unbridled, uncontainable, rebelliously and irreverently psychoanalytical. It is ineluctable, inescapable, reassuring and damaging, and Jean Frémon captures with superb intensity precisely those dyads of enchantment and horror, of fellow-humanity and monstrosity, of intimacy and savagery.

Bourgeois wrote and spoke, her words can be read and have been transcribed, like ancient oracles, irresistible in their allure and promised wisdom, indecipherable in their poignancy and darkness. From Mâkhi Xenakis’ Louise Bourgeois: l’aveugle conduisant l’aveugle and Louise, sauvez-moi! to Bourgeois’ own commentaries on her work or diary fragments and entries, we have her reverberating, unsilenceable voice. It is a voice that is both torrential and elliptical, governed by an almost extreme sense of order and logic, as well as being unbridled, uncontainable, rebelliously and irreverently psychoanalytical. It is ineluctable, inescapable, reassuring and damaging, and Jean Frémon captures with superb intensity precisely those dyads of enchantment and horror, of fellow-humanity and monstrosity, of intimacy and savagery.

Frémon had a privileged experience to draw upon – he had known Louise Bourgeois for almost the entirety of her artistic life, he was her agent, respondent, critic and collaborator. What he offers us is an intimate, particularly sensitive account of another human being’s very public lament and battle cry, an exclusive view that includes both heaven and inferno. He conjures up a personal vernacular, an incantation of traumas that became a terrible power, the artist’s relentless, unconquerable force of both creation and ruin.

Frémon is an astute close reader, and he captures for us the fascination that spiders held for Bourgeois, the double-binds of fathers, husbands, mothers, children, the symbolic space that clashes with and nurtures reality. His novel is in fact reminiscent of a solitary spider huddled in a corner weaving the web of both mortality and immortality – now fast, now redolent, dense, sparse, elliptical, magnificent, shredded and torn. He infuses this imaginary true story with Bourgeois’ indomitable will to live (she died at nearly 100, after all), underpinned by an equally irrepressible death drive or sense of total despair, urging us to listen to her long, sostenuto, sotto voce wail.

Now, Now, Louison is a compulsive exploration of the role, power and symbolism of maternity, fertility, sublimation and reality, ecstasy and happiness, silence and the overcrowding bustle of belonging.”

His story is both a vivid portrait and an engrossing dialectic with art – its purpose and process, the minutiae of its eternity, the grittiness of its daily practice and existence. Now, Now, Louison is deeply, troublingly private and thrillingly theoretical, provokingly authoritative over another human being’s definition of all that she was or yearned to be. It is a compulsive, daringly perceptive, sometimes astringent exploration of the role, power and symbolism of maternity, fertility, sublimation and reality, ecstasy and happiness, silence and the overcrowding bustle of belonging; of hysteria and emotionality, of how to give material substance to presence, to nothingness and the void.

Frémon’s Louise is like the woman who wakes up to a non-existent language in Marguerite Duras’ Le Shaga: she is as verbal, as plethoric, as Other and as quintessentially representative of all that each of us can ever be. Reading Now, Now, Louison is not a straightforward literary exercise – unless one is willing to listen rather than pull the strings of both narrative and life into neat patterns, perfect phrases or frames of polaroid images. It feels, in fact, like a casual visit, extraordinary and natural at the same time, to Bourgeois’ New York studio/home at 347 W 20th Street. Frémon conveys the chaos and order, the fierce tenderness, the pathology and the rare humanity of Louise Bourgeois, with pathos and even love. As Bourgeois once said, “The subject of pain is the business I am in”, and Frémon in this novel clearly understands both pain and catharsis.

Jean Frémon is a gallerist and writer. Since 1969 he has had over twenty works published, including novels and poems (some translated by Lydia Davis), as well as essays on art. In 1985 he commissioned Louise Bourgeois’s first European exhibition. Thirty years later, he organised her last, which she curated, at the Maison de Balzac in Paris. He has also worled closely with other artists including Antoni Tapies, Donald Judd, Jannis Kounellis, Sean Scully and David Hockney. Now, Now, Louison, translated by Cole Swensen, his first book published in the UK, is out now in paperback from Les Fugitives.

Jean Frémon is a gallerist and writer. Since 1969 he has had over twenty works published, including novels and poems (some translated by Lydia Davis), as well as essays on art. In 1985 he commissioned Louise Bourgeois’s first European exhibition. Thirty years later, he organised her last, which she curated, at the Maison de Balzac in Paris. He has also worled closely with other artists including Antoni Tapies, Donald Judd, Jannis Kounellis, Sean Scully and David Hockney. Now, Now, Louison, translated by Cole Swensen, his first book published in the UK, is out now in paperback from Les Fugitives.

Read more

@LesFugitives

Cole Swensen is an American translator, poet, editor and a professor at Brown University, Rhode Island. A finalist for the National Book Award in 2004 and the recipient of a PEN USA Award for her translation of Jean Frémon’s The Island of the Dead, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2006.

coleswensen.com

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.