No subject

by Brittney Inman CantyIt was only a couple of months ago. She was at the office settling in at her desk when she noticed ‘No Subject’ waiting in her email. It seemed strange for her aunt, a notorious perfectionist, to have left the subject line blank. She guessed it had something to do with her father, whose sixtieth birthday was coming up. Since it was a big birthday, and he had stayed sober and out of jail for almost a year, she’d been thinking about sending him a card this time. She knew he would be overjoyed to receive something from her, but she never indulged him because it didn’t seem fair that after leaving his family for drinking and Hollywood dreams, he should still get to receive birthday cards from his daughter.

Leaning back in her chair, she took a sip from her mug of gingerbread-flavored coffee. Though it tasted artificial and watered-down, it was warm and smelled like Christmas, and that was enough to provide the bit of morning relief she craved between waking up and starting the day’s work. But today ‘No Subject’ invaded that space, drawing her attention – and worse, her imagination – to its possible contents. It felt like a trick, like an unlabeled box left on one’s doorstep as either a threat or a gift.

She hugged the mug with both hands to warm her fingers, which were still chilled from her walk to work and surveyed the office. Her co-workers were filtering in and hanging up their coats. It was an open work environment with Ikea desks, Mac computers, and walls that doubled as dry erase boards. She liked the idea of working in an open space like this, but often she wished for more privacy, room for her thoughts to drift. Did her boss, who sat in the row behind her, notice she was sitting idly at her desk for perhaps too long? She glanced back to find her, spooning yogurt into her mouth, headphones plugged into her ears, engaged in something on her screen.

Her coffee was getting cold; the milk had congealed in a thin top layer. It was just an email, just a fucking email. Her aunt probably wanted to throw a birthday party for her father at her fancy country club and pretend they were all one big happy family. “Do it for your grandparents,” she would say, “who knows how much longer they’ll be around?” She pulled herself close to the desk. Trying to obscure as much of the screen as possible with her head and shoulders, she clicked: “Paul has died. I am in shock that’s all. Do you know already? I don’t know what to say.”

The words seemed to run away from her as she read them over and over again. She felt panicked for not being able to keep up, not being able to catch and hold them in her mind. A kind of exhilaration took over her, a heightening and sickening sensation, like she was soaring upwards more quickly than her body could go. It almost made her want to laugh.

“What?” she replied, noticing that her fingers trembled as she typed, and hit send. Not waiting for a response, she left the office without speaking to anyone and started walking. A frigid gust of wind made her realize she’d forgotten her scarf, but she decided against turning back to retrieve it. Besides not wanting to face her co-workers, she felt an urge to surrender herself to the cold, to some kind of oblivion.

“Excuse me,” a man said, approaching with a clipboard, “do you have a moment for green energy?” She looked up at him and shook her head. “Oh, I’m sorry,” he said. “You’re crying.”

‘Dad,’ she said, and waited a moment before hanging up. It felt like every part of her being was saying his name, as if she could resurrect him by calling out to him from some deep part of herself”

At last she sat down on an empty bench in a small park with a patch of dead grass, a few leafless trees, scattered pigeons, homeless people and professionals on break. She called her father’s number and listened to his recorded voice say: “You’ve reached Paul Fields. Please leave a brief message, and I’ll get back to you as soon as possible.”

“Dad,” she said, and waited a moment before hanging up. It felt like every part of her being was saying his name, as if she could resurrect him by calling out to him from some deep part of herself where she might still be connected to him.

Staring at the bare branches of trees and the pieces of sky in between, she tried to conjure him: his pale blue eyes, bright with pride, passion, and revelations about the meanings of words and money-making schemes; his thick eyebrows, which seemed to bear down on his eyes, giving him an air of earnestness that always used to charm her into forgiving him; his hair, curly and black, like hers; and the way his mischievous laugh would break out under his breath to betray his seriousness and make him a boy again. She felt desperate to recall every detail about him and inscribe each one upon her memory.

An image of her father with a knife held to his wrist came to her mind. He was gently running the blade across his skin making red-pricked scratches and threatening to press harder. His eyes were bloodshot, his pants sagging to one side. She saw herself hiding behind her mother.

Maybe her aunt was mistaken; maybe he’d survived. Hadn’t he survived so many times before? She checked her phone to see if her father had returned her call, and the words from her aunt’s email came rushing back.

And again today: Paul has died. Did you know already? Paul is dead. Did you know?

It’s as if the voice in her head has always known about this death – her father’s death. When she’s alone, it starts as a whisper, allowing her to continue going about her day, but once she turns her attention to it, the words grow steadily louder, drowning out everything else until there is nothing she can do but give herself over to them.

On days like this, her husband comes home to find her heaped in bed, her body drinking in the light, which pools in the middle of the white bedspread as the sun begins to set. He sits next to her and says, “How’s my birdie doing,” putting his hand on her damp cheek. She can smell the chalk on his fingers and feels the tears come back to her eyes. She doesn’t respond. She just goes on staring out the window at the clouds and the sky’s changing colors. He runs his fingers through her hair and hums something that sounds more like a made-up language than a tune.

She drifts into a half-sleep, part conscious thought and part dream, where her father is still alive, his blue eyes beaming. They’re hiking along the desert trail that they’ve hiked so many times before, and he’s naming the different types of cacti as they go. Saguaro, prickly pear. The trail leads them to Bridal Wreath Falls, where boulders that look like dinosaur eggs nest in a sandy bed beneath the trickle of a small waterfall. They lie on their backs stretching out across the smooth, cool surface of the giant rocks. Her father tells her to be very quiet and still. “Listen to the desert,” he says.

She listens to the splash and plunk of the water against the rocks and sand. She listens to the parched brush stir and crack in the breeze. And she listens to her father’s breathing beside her, which is full and balanced. She knows this way of inhaling and exhaling is deliberate, concentrated; it’s one of his practices in the art of being in the present moment. Remembering this, she feels overcome with a searing sense of compassion for him. Her waking mind looks on from above, and watches the two of them lying there in the memory of that sacred place, where she sees herself as a child reaching over to rest her miniature hand in his – a gesture she wouldn’t have made in real life. Her hand curls up against his palm, as they continue breathing and listening to the world around them.

Brittney Inman Canty earned an MFA in creative writing from The New School. Her writing has appeared in New Plains Review, In Posse Review and other publications. She lives in Brooklyn.

Brittney Inman Canty earned an MFA in creative writing from The New School. Her writing has appeared in New Plains Review, In Posse Review and other publications. She lives in Brooklyn.

Follow Brittney on Twitter: @BrittCanty

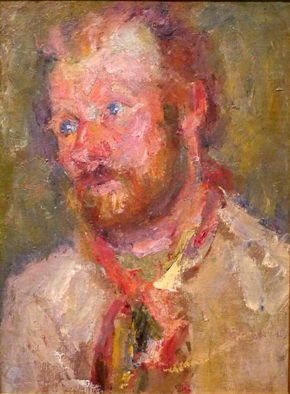

Author portrait © Bethany and Dan Photography