The rain

by Tove JanssonThree motorboats rushed across the water, their bows abreast. The sun shone and the boats they met waved and assumed they were having a race.

In the middle boat, the broadest of the three, an old woman lay on a litter. The litter was made of an old red deckchair stretched out full length and supported with oars. It was narrow enough to carry through a door.

She lay with her head turned away. Her hair was very white and she seemed suddenly and surprisingly small. The boats maintained the same speed all the way to the bus pier, where they slowed and beached at the well-trampled landing where the cars and boats of the summer people came and went and where everything was proceeding normally until the ambulance arrived. Then everyone put down their bags and baggage and thought, Dear Lord, right in the midst of vacation, and they took a grip on their children to keep them from running over to look. An old woman in a sunhat bent over and tried to look into the unfamiliar, averted face. She wasn’t being nosy, she just recognised the situation and said to herself, Poor soul.

In the general store they tried to figure out what might be needed in the ambulance and bought Vichy water, candy and tissues.

It was hot in the ambulance. The driver knew his stuff. “Do you have any nitro?” he asked. Apparently the people who drive ambulances have to know a lot; maybe they get special training. The attendant who sat beside her just sat there, quiet and serious. He was very young and looked as if really, by natural right, he should have been somewhere else entirely. The road twisted and turned its way through the parched landscape. Once, perhaps, it had been a path, threading its way among houses and boulders and small fields. Then it grew broader, and no one stopped to think that it widened and hardened into a motor road precisely because it had always avoided obstacles.

It was a hot day and there was a thunderstorm that night. The hospital was long and low and a corridor ran through it from one end to the other. It was the darkest time of the night, but no lights were needed now in summer. All the doors stood open, and the people who lived inside them were quiet. Maybe they slept and maybe they listened to the thunder.

It was a beautiful thunderstorm. The architect who built the hospital had included a large balcony at one end of the corridor. From it, one could see the solemn garden with its asphalt paths, black with rain. A few nighttime cars drove past at long intervals. The whole landscape was filled with the storm’s cold, greenish light, the trees unmoving, like painted scenery in a long and lonely stage perspective. The thunderstorm sailed over the garden, its lightning bolts white and chilly blue, losing themselves in the summer night.

The hospital was near the coast and now, just before dawn, the gulls were screaming above the shoreline. There must have been hundreds of them, all crying, the sound rising and falling, louder than the thunder. For anyone listening, their cries were like panting, like a pulse, a fervour, filling the night.

The gulls went silent when the sun rose, and the rain was brief.

The corridor was so long that it seemed to end in a point of darkness. But the whole length of the corridor glowed with the greenish light that permeated the night outside and flowed in through the open doors.

She loved thunder, but this lovely storm was probably too quiet, it never really reached her.

What is it that cuts across the breathless, brief, and occasional periods of sleep as a very tired human being dies? It cannot be merely the tormented need for more air, for water, or because everything slows and chokes as it rushes towards dissolution, towards the implacable and utterly alien transformation of the body. The old woman was visited by images, events from the life she had lived or dreamed. Everyone was with her, maybe not only those who had loved her and lived with her but also those who had slipped away, the opportunities she’d lost.

There is no way to know. We know nothing but try to find explanations in a smile and a few words that come from far away, from another world, more real than reality.

Death can be a stopping, simply a going quiet. To listen to the sound of breathing for a long, long time, to laborious life fighting to continue, to life forced to continue and to run through tubes and catheters until suddenly none of them are needed and they can all be removed and hung up on their hooks and rolled away on rubber wheels. The one who dies is utterly clean, utterly silent, and then, from the grey mouth, from the altered face, comes a long cry. It is commonly called a rattle, but it is a cry, the exhausted body that has had enough of everything, enough of life and of waiting and enough of all these attempts to continue what is finished, enough of all the encouragement and the anxious fussing, all the loving awkwardness, all the determination not to show pain or frighten those you love. Death in all its variety has a million forms, but it can also be the death of a long and very weary life, a single cry, an articulation of finality, the way an illustrator completes his work with a vignette on the final page.

The thunderstorm gave the parched landscape only a quick shower.

The big rain came several days later. It started raining just before dawn, across the mainland and across the islands. Wells and water barrels filled, there was a rustling and roaring on every roof, and the rain went on and on. The soil was so dry that it was crisscrossed by cracks, and the moss came away from the granite faces in hard plates. Now all the earth, all the moss, all the roots filled with water. The rain dashed down over the whole countryside in a blessed overabundance, and inside the houses people lay listening and thought, This is good, and then turned over and fell asleep.

From The Listener, translated by Thomas Teal.

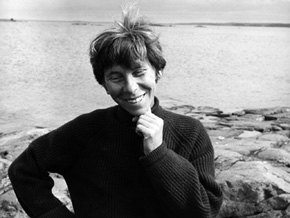

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a Finnish-Swedish writer and artist best known as the creator of the Moomin stories, which were first published in English sixty years ago and have remained in print ever since. In her 50s she began writing for adults, producing a dozen novels and story collections including the classic bestseller The Summer Book. The Listener, her first story collection, was published in Swedish in 1971 and now appears in English for the first time, published by Sort of Books. Read more.

Tove Jansson (1914–2001) was a Finnish-Swedish writer and artist best known as the creator of the Moomin stories, which were first published in English sixty years ago and have remained in print ever since. In her 50s she began writing for adults, producing a dozen novels and story collections including the classic bestseller The Summer Book. The Listener, her first story collection, was published in Swedish in 1971 and now appears in English for the first time, published by Sort of Books. Read more.