The world that watches

by Mika Provata-CarloneEach of us, to a greater or lesser extent, with varying degrees of enchantment or epic promise, is both a myth and a dry ledger of facts; a fantastical spectrum of stories, our own and those in the minds of others, as well as a hard surface of all or the little that there is.

Iris Origo was one of those twentieth-century figures whose aura of legend has become almost inextricable from the realities and the res gestae of her existence. She emerges aloof, magnificently distant, yet also disarmingly close, an almost impossible, improbable exotic dream, full of the very best stuff of an everyday life.

That this everyday life was extraordinary, by any means or measure, goes without saying, and it must have been both mesmerising and disconcertingly difficult for anyone close to her to keep up the pace – then, but also now, when the memory of Origo seems to be not just an urban legend but a vigorous enterprise of historical and individual assessment and definition.

Katia Lysy’s afterword in A Chill in the Air brings this out quite handsomely. Every effort to conjure up the woman, mind, era and class that was Iris Origo is fraught with obstacles: of selection, of angles of interpretation, of silencing or suppression, of sincerity, of veils of existence – and Origo possessed so very many of the latter.

Perhaps the fairest assessment of her would be one that allows for her almost superhuman powers of enchantment to shine through, while admitting both the darkness and the light, the clarity and the ambiguity, the truth and the nebulousness, the delicacy and the absolute, unyielding power that were also hers, and part of that irresistible force that she exercised and claimed throughout and beyond the span of her life.

A Chill in the Air begins on 27 March 1939; it ends, abruptly, in July 1940, with the forthcoming birth of a child – also with the capitulation of France. That March of 1939 was full of portents and glitter. A new pope was being elected; Shirley Temple’s The Little Princess and Laurence Olivier’s Wuthering Heights were released; Germany took Czechoslovakia and claimed the Rhineland; Francoist forces in Spain would gain the upper hand and the second Sino-Japanese War was well under way; a conspiracy theory was being circulated that the real Adolf Hitler was dead and an impostor had taken his place; Salvador Dalí caused a hoo-ha in New York; Lithuania was invaded by Germany and works of ‘Degenerate Art’ were burnt; on the 27th, Germany began its propaganda campaign against Poland, denouncing “the oppression of Germans in German lands now controlled by Poles”; Newsweek ran an article under the caption “Nazi Caesar”.

Unlike her other published writings, this is, at least at first glance, an unfiltered record of her thoughts, her gut reactions and her innermost reflections on a momentous time in history.”

Some of these events seep through into Origo’s diary; some evade her field of vision. Unlike her other published writings, this is, at least at first glance, an unfiltered record of her thoughts, her gut reactions and her innermost reflections on a momentous time in history to which she had an especially privileged insight to offer. The “chill in the air” is “the universal dislike for Germany as an ally” that Origo seeks to attest in her fellow Italians, whom she determines to see, above all, as “groups of bewildered country boys with their bundles or little fibre suitcases… with the dazed patient look of their own cattle” or as benign, well- educated, pious urbanites mulling over the antics and monkey tricks (as they call them) of Hitler and Mussolini, while hoping, with almost irresistible dolce far niente, that peace and reason will prevail against all odds.

Origo was a uniquely placed observer of all that was happening around her and further afield, and her chronicle of day-to-day events has a deserved breathtaking feel to it. As one of the ‘locals’ in Italy, as an American and as an English woman, as privy to circles of influence, intelligence and action far beyond the reach of most but a very few (William Phillips, the American Ambassador to Italy, was her godfather and a regular visitor, to mention only one example), she was also possessed of a particularly well-trained and shrewd mind, a keen curiosity and a sharp, analytical eye. As the true cosmopolitan her father wished her to be, she was able to penetrate cultures, mentalities, histories, to see through trends and into tendencies.

Family life goes on: Antonio and Iris Origo with second daughter Donata at Foce in 1943. Wikimedia Commons

We see her travelling almost incessantly across Italy throughout her diary, recording minutiae as well as events that would shatter the existence of many across the globe; she is shocked by Fascist propaganda, exasperated by the coverage of truth and of untruth in the national and international press, enjoys “tea with some charming anti-Fascist neighbours” and provides her readers with ironic twists on global historical developments: the tax-duties on Italian silk that incur the rage of Italian authorities and the Machiavellian justification for Mussolini’s future measures, also deprive the Origos of a much longed-for (and presumably lavishly paid for) American tractor; the first air raids that she will experience in Rome towards the end of A Chill in the Air were “altogether a singularly unalarming experience, except apparently for the lions in the Zoo, who went on roaring all night.”

With a fine flair for juxtaposing the unalarming with the leonine roar, Origo powerfully evokes, and often contrasts, the three angles of vision available to her: the ‘educated people’ and her circle of diplomats, friends and politicians; the newly enfranchised peasant class and the men in the streets – whom she calls the popolino; and finally the official state machine and press propaganda. She is determined to expose the disjunction but also the convergence between each and all three. In doing so, she offers us a rare spectrum of forgotten voices, neglected episodes and buried stigmas, which reveal not only Origo’s vast erudition and intellectual acumen and engagement, but also the versatility of her perception. She reminds us of Dean William Inge’s anti-Semitism and Roosevelt’s failed, utopian plan for the creation of a Jewish state comprising Kenya and a portion of Southern Abyssinia; of the bartering efforts between France and Italy as Germany advances; she evokes for us the eerie echoes of Max Plowman’s verses and reminds us of Olaf Kullmann’s or John Macmurray’s struggles against the grain of the historical process of the 1930s; she reveals her keen interest in the latest accounts of the state of things in Germany, having read Nora Waln’s prophetic (and all but ignored) Reaching for the Stars and The Approaching Storm almost as soon as they were published – they were among the first testimonies to expose Germany for what it was in its everyday reality and in its official image.

From each of these perspectives, Origo’s diary is a gripping statement of determined presence against erasure. It can join, now that it is finally published, Christabel Bielenberg’s The Past is Myself, or even Victor Klemperer’s I Shall Bear Witness, for it is exactly a confrontation with the past, its conscience and its consequences that Origo seeks, in giving herself the role of chief and impartial witness. The agency she concedes to herself as the chronicler of that past is unmistakable – as it is, in many ways, almost total. And this is perhaps where Origo fails to attain her proclaimed purpose. She suffers, not infrequently, from double-vision, appearing to stare with clarity at what she also seems quite willing to obfuscate through innocent (or not so innocuous) smokescreens. It is chillingly hard to miss the seemingly fleeting reflection that it is “impossible… not to feel that Fascism was, in its beginnings, a genuine revolutionary movement of the people. Easy to see how they have been worked up to hatred of the countries presented to them as ‘obese, capitalist, decadent’ – to identify Fascism with the good of the working class”; or how she admires Mussolini’s agricultural policies and the need for order, just as she denounces the complacency of “honest and honourable” Italians, their easy compliance with Fascism.

Origo is invaluable in her skills of showcasing documentary evidence, of seamlessly creating her own narrative of what occurred or transpired.”

What she witnesses, she calls a “curious, passive fatalism” – and one can extend this observation perhaps, at her urging, to include the curious, passive Fascism she is resolute to describe throughout. As a result, there are perhaps two ways of reading this singular, unmissable account: with a disciple’s willingness to believe it, to give it unquestioned credibility as an unfailingly true chronicle, faithful to the pervading atmosphere; or with historical acuity and analytical poise that does not underestimate the human dilemma and moral difficulty of existing on so many, often mutually clashing planes. The demand for ‘authenticity’ then crumbles, and what remains, quite majestically, is Origo’s admirable loyalty to a people she was determined to call her own.

In a sense, the greatest “chill in the air” is to read the quoted Fascist bulletins and news statements from the perspective of Paul Reynaud’s faith in “the world that watches [and] will judge”. Their resonance with many current voices in power will be numbing to all for whom clarity of thought still matters. Origo is invaluable in her skills of showcasing documentary evidence, of seamlessly creating her own narrative of what occurred or transpired. Readers will perhaps inevitably feel that there is a bias in the attribution of cause and effect, of right and wrong, of agency and passive endurance. Yet no reader will fail to be captivated and engrossed by the irreducibility of Origo’s voice, by her larger-than-life awareness of a place and purpose in history. This is a revealing addition to the corpus of Origo’s writings, one more hue of startling colour and contrast to all her images and shadows.

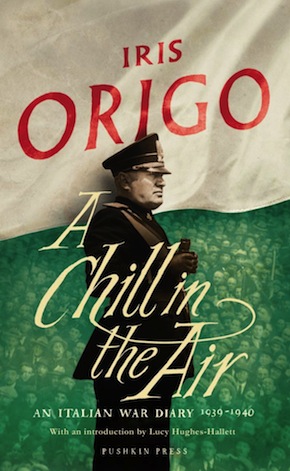

Iris Origo (1902–1988) was a British-born biographer and writer. With an introduction by Lucy Hughes-Hallett, award-winning author of The Pike, and an afterword by the author’s granddaughter Katia Lysy, A Chill in the Air is the gripping precursor to Origo’s bestselling classic diary War in Val d’Orcia. Both are published by Pushkin Press, along with her other memoirs and diaries.

Iris Origo (1902–1988) was a British-born biographer and writer. With an introduction by Lucy Hughes-Hallett, award-winning author of The Pike, and an afterword by the author’s granddaughter Katia Lysy, A Chill in the Air is the gripping precursor to Origo’s bestselling classic diary War in Val d’Orcia. Both are published by Pushkin Press, along with her other memoirs and diaries.

Read more

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London. Read her review of Iris Origo’s Images and Shadows and War in Val d’Orcia:

Seduced by utopia