A disunited kingdom

by Nadia Attia

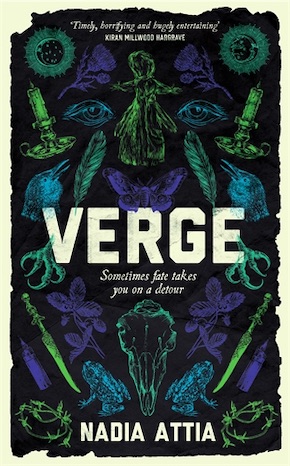

Let me paint you a picture of an alternative Britain sadly not too far from our own… My debut novel Verge charts a journey – both literal and internal – of two very different young people across a Disunited Kingdom where the county borders have become hard borders with checkpoints, processing units, guards and, occasionally, guns. Each border crossing requires a passport, electronic work permits from an employer and – particularly if your skin is anything other than white – a certain level of scrutiny from those in control of the barriers. If you’re not offering goods or services, if you don’t have family ties to the county or special dispensation you’ll likely be turned away. In Verge each county is incentivised by the government to increase productivity; those that fall behind are left to go to ruin with ghost towns an ever-increasing occurrence, places where only the ‘Sallys’ (salvage collectors) might eke out a living. Horses are more prevalent than cars due to the cost of fuel, petrol stations are branching out to become coffee-shop ‘hubs’ in order to maintain footfall, and the government has dropped the driving age to encourage people back onto the roads. I combined imagination with pragmatism and logic in my world-building , and used the setting as an antagonist for my two heroes, with bureaucratic and sociological obstacles – and nature itself – getting in the way of their goals.

“There was plenty of work in construction, land registry and surveillance in the early years of the Split, when county borders were made hard and had to be monitored for access – so much so that people thought the economy might withstand being cut off from the Continent. Yet as fast as these geological surgeons could add their steel scars to the map, more bits of land were dropping into the sea or being flooded beyond salvation.”

In Verge, climate change has made swathes of farmland barren or flooded and the sea has eaten away at what’s left. Political choices have isolated the Kingdom from Europe and the rest of the world, adding to the sense of ‘them and us’. Sound familiar? I wanted to create a tinderbox for xenophobia and racism; a place where outsiders are tolerated at best, where each scrap of fertile ground is something to be fought over and protected at an increasingly high and questionable cost.

I wanted to explore the lengths people might go to in order to survive under such pressured conditions, and it made sense to me that folk – particularly those from working-class or remote rural backgrounds – would return to the old ways of spells and superstitions. If the government has abandoned you, if the land is becoming infertile and you can no longer afford the cost of medicine, fuel or materials, you’d be forced to re-examine your relationship to the natural world, and you’d become even more resourceful and ruthless, right? Who would you pray to if nothing else has worked, if you don’t feel listened to? In Verge predominant religions sit alongside pagan belief, and cunning folk have replaced GPs in most small towns; I don’t dwell on these things or pass judgement on what’s right or wrong because it just made sense that people would adapt to survive. It’s amazing how quickly major life changes can become ‘the norm’ – just look at how we reacted to the pandemic.

If the land is becoming infertile and you can no longer afford medicine, fuel or materials, you’d be forced to re-examine your relationship to the natural world, and you’d become even more resourceful and ruthless.”

By now I’m sure it’s quite obvious what my influences were: through my writing I wanted to dig into the disappointment I felt at Brexit and the increasing divisions in society, but I also wanted to tap into my love of nature, British folklore and folk horror. Verge became even more meaningful to me when the pandemic hit and many were suddenly reawakened to nature and found a desire to rewild themselves. More recently, with the Right to Roam movement, people have been fighting to reclaim the land that’s been denied them. When 92% of England is fenced off and (mostly) in the hands of wealthy landowners, it underscores the sense of injustice that so few are sitting on so much. Add to this the cost-of-living crisis, heightened tensions around UK border controls and racism, and I’m unsurprised that what I wrote in 2019 has only increased in prescience over the past four years.

Despite all this, I still wouldn’t describe Verge as a dystopia – for me it’s more a story about two people forging their own path in the face of adversity (from without and within). There’s humour, hope and wonder, and a message of resilience and rebellion, a sense that we can call things out and push against expectation. I sincerely hope you enjoy the ride…

—

Nadia Attia’s debut novel Verge is a folk horror-tinged road trip across a divided, alternative Britain where people have returned to the old ways of spells and superstitions. Nadia comes from a working-class background, has Egyptian-German heritage and is drawn to stories of otherness and the supernatural. She’s a BFI Network Talent Executive, a published film journalist and a freelance film/TV script consultant. In 2019 she was a participant in Spread the Word’s London Writers Awards and won the FAB (Faber) prize for fiction. A graduate of the Curtis Brown novel-writing course, she has had her work published in Spread the Word’s City of Stories anthology, Star Songs and Luna Station Quarterly, and is currently working on her next novel. Verge is published in hardback and eBook by Serpent’s Tail.

Read more

nadiaattia.com

@nadia_land_

@serpentstail

Author photo by Louise Haywood-Schiefer