A time to write

by Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi

It’s difficult to cast my mind back to the early days of the pandemic, even though it wasn’t so long ago. Maybe because it’s a stressful time that most of us would rather forget, or maybe since many of our deeply rooted memories have to do with human interaction, it is difficult to understand, to remember, to process, a time of absence of contact. I remember learning that there is indeed a thing called ‘skin hunger’; and finding something both luxurious and despair-inducing about reducing the proportions of a recipe in order to make a cake-for-one; and, even though it now seems like it’s been around forever, discovering Zoom. In the early days I did all the cliché things: I took up embroidery; I taught myself to hula hoop; I wrote poetry and bought an enormous exercise bike that now takes up half my living room; I wrote more poetry; I didn’t make home-made bread but I bought the flour and yeast; and I stewed. I stewed and stewed and stewed, without knowing quite what I was marinating.

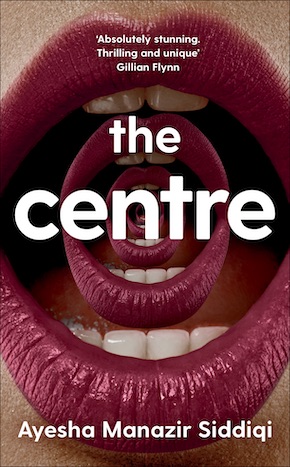

Then I adopted a kitten. Little Billee. And a few days later, my friend Sakeena invited me to join her Zoom writing group. Sakeena was processing a challenging experience at the time, and she’d brought her story into the writing class, so in part my motivation was to understand it and thereby her better, and simply to spend time with her in a moment when our socialisation was limited to the virtual. And also I wanted to work on my work. I’d been writing for many years then, poems and short stories and essays mainly. And so I intended to submit a short story when my turn came around for workshopping, but then something shifted and I decided to work instead on a kernel of an idea that I had had in my mind for some time – a woman discovers a highly exclusive and seemingly miraculous language school that promises fluency in any language in just ten days, but at a secret and sinister cost.

As I wrote the novel, I found myself processing the details of my own life. The protagonist, like me, moves from Pakistan to England at eighteen for university. Now, with the borders closed because of Covid, I was cut off from my parents and siblings, and found myself reckoning with this move that I had made, with the ambivalence I felt towards the place I had chosen as my home. The themes of migration, appropriation, privilege, gender and race worked their way into the novel as I grappled in this way with my own insides. And, as the novel moved through Karachi, London and New Delhi, I found myself revisiting portions of my own past. I began by writing a chapter or so, and I sent it to the writing group. Unlike my usual writing circles, the group consisted of people who wrote mainly for pleasure and weren’t necessarily even looking to publish, and this made for an encouraging, non-judgemental space that turned out to be just what I needed. And so I continued making my way through the story, sometimes painstakingly and sometimes joyfully.

Billee and I, in that sunny flat, would eat and play, hunt and wrestle all day long. We would track the movement of the sun across the living room carpet and cough up the occasional hairball as we made our way through that quiet bubble of time.”

It was then that I started to understand the upsides of the pandemic – how the curtailment in social contact allowed me not just the time to write seriously but also the head space – the possibility of not censoring myself as much, of being less conscious of the opinions of others. I moved a few steps closer to myself during the pandemic, accepted parts of myself I’d previously pushed away, allowing for more vulnerability to come to the surface. Billee and I, in that sunny flat, would eat and play, hunt and wrestle all day long. We would track the movement of the sun across the living room carpet and cough up the occasional hairball as we made our way through that quiet bubble of time. At first I wrote for maybe twenty, thirty minutes a day, but eventually the novel took on a life of its own, gaining momentum, and then I could write four or five hours a day with ease. And when I went for walks, it was sometimes as if I were walking through the novel itself, page by page, chapter by chapter. I was in flow, and it was wonderful.

Then the pandemic receded. The numbers went down. People were socialising again. And I found myself worried, slightly, that as the masks were slowly coming off, would the one I had shed come back on? And so I eased into post-pandemic life slowly, allowing myself the possibility of re-assessing my yes’s and no’s, of giving in to certain pressures less. I found some of my friendships shaken by these new dynamics, and I felt more aware of previously problematic patterns and more respectful of my introversion, my need for space, and more grateful for the beautiful things that can arise from there. I also finished the manuscript. I sent it to The Literary Consultancy in London, who were great, and confirmed to me that what I had written was indeed a novel, and potentially publishable. Then I worked on it some more before sending queries out to agents. And now, two years on, the book is on the shelves. And the other day, to my delight, I saw that some people had posted photos of their copy of the book next to their cat. I responded in turn with a photo of little Billee reading his name in the dedications.

Sometimes I fear that since it took such an extreme and hopefully never-again scenario to finally get my butt on the chair and write the thing, will I be able to write another one, now that life has started to stir again? I really hope so. The prayer is that I will have the discipline and courage, the support and confidence to stick with it. This roller coaster of a time has been very different than I imagined, and I am still learning how to savour the gifts, to understand that they can come from unexpected places, and to fully inhabit the moment that I’m in now, for better or worse.

—

Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi is a writer and editor. She has published essays, reviews, short stories, poetry, monologues, and translations. She has also written for radio and for the stage, and she was contributing editor for the Trojan Horse Affair, a podcast by Serial and The New York Times. The Centre is published by Picador in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@tweetingayesha

@picadorbooks

Author photo by Andrew Mason

“In her ingenious debut novel, Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi introduces us to a world where language learning doesn’t stop with a textbook. The would-be polyglots in this thriller aren’t just striving to memorize verb conjugations and recite poetry; they’re up to something far more sinister… This is a book whose many delights and horrors are unlikely to be lost in translation.”

The New York Times