Amy Liptrot: Wired and watchful

by Mark Reynolds

“It’s this aptitude Liptrot has for marrying her inner-space with wild outer-spaces that makes her such a compelling writer – and one to watch.” Will Self, Guardian

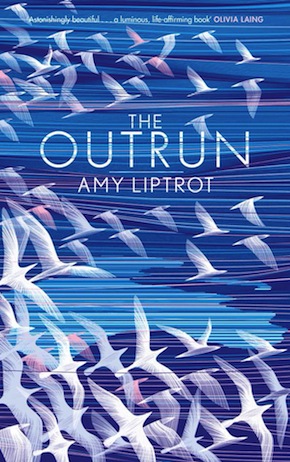

Amy Liptrot’s astonishing debut memoir The Outrun is a brutally honest tale of inglorious addiction in hipster-central Hackney, and a lyrical meditation on the long path to recovery after she washes up back home on the clifftops of Orkney. Plunging into nature on the remotest islands, she dissects her desperate descent into alcoholism and the loss of jobs, loved ones and lodgings, and embarks on new discoveries that offer hope and renewal. I catch up with her to reflect on a dizzying week that saw the book serialised on Radio 4 and accrue a host of admiring reviews, media attention and discussion.

MR: Why did The Outrun strike you as the perfect title?

AL: As I describe in the book, it is the name my parents gave to the top stretch of coastal land on the farm where I grew up. It’s an old agricultural term. You have the ‘in-bye’ land which is close to the farm and the ‘out-bye’ or outrun which is uncultivated. I just like the mood of it. It’s got potential for quite a lot of different meanings or metaphors – the idea of escape or an energetic spirit, or the idea of always trying to outpace something. I’d leave it fairly open to interpretation, but I think the title did inform the aesthetic of the whole book. If you have a title, you know where you’re heading.

How are you wired that made you susceptible to addiction, and to alcohol in particular?

It’s a very complicated question, which I explore in different ways in the book, and it’s something that medical professionals and psychoanalysts argue over and I’m still not completely clear on myself. But I certainly think from when I very first started drinking, there was an urgency to the way I drank that was unusual. I don’t think it’s to do with circumstances, the people that I hang around with or things like that. And there are studies that say that children of people with mental health problems are statistically more likely to have addiction problems, so I think my father’s mental illness could well have something to do with it. But the urgency with which I drank and the fact of alcohol being an end in itself rather than a social lubricant I think was there pretty early on, and the classic thing of once you have one drink, not being able to stop for the night until you fall down.

How many times had you tried to quit before you entered the council-run rehab programme?

Many times, including by force of will, starting from the simple wake up with a hangover on a Saturday morning and say “I’m not going to drink again” but by Sunday night you’re having a drink, to telling my boyfriend or my brother that I was going to stop and believing it myself but only managing to get to a few days. I went to a doctor and was sent to drink counsellors and had to write a drink diary. I was going for a while at 2 o’clock on a Friday afternoon and I’d say – and I meant it – that I’d stick to no more than four beers a night. And Friday night – I’d always do this – I’d go to the shop and buy two beers and think I’m just going to have the two, and I’d always be back in the shop half an hour later buying four more. Then I was prescribed Antabuse, which is a drug that if you drink on it you have a severe allergic reaction. But I kind of plotted against myself, to stop taking it and not tell the doctor. And I did drink on it. You’re meant to take it for seven days and I started drinking after six days, which makes you feel really stoned. It’s not for other people or a drug like that to put a limitation on it; it’s got to come from yourself. I had about four different attempts where I got to about a month each time, and I’d gone to AA meetings for four or five years before the time I went to the treatment centre. And so far, coming up to five years, I’ve managed to not drink. But it’s still something to remain vigilant about.

If I think about having a drink, I remind myself I’ve written a flipping book about staying sober, so at the least it would be hypocritical.”

How was it when you first walked into that programme and found yourself among East London’s messed-up criminals and dropouts?

I was the girl that was always crying. I cried so much during those three months, and a lot of it was just shock at finding myself there: how was this my life, how have I ended up here? It’s a contained environment, and a lot of laughter goes on in these places, and a lot of honesty. There’s this group therapy when you sit round in a circle and talk honestly about stuff that’s happened in your lives, and I’d never been in that kind of environment before, and there can be quite a bit of dark humour.

And the spectre of a sharp drop-out rate, I suppose.

Absolutely. I wasn’t quite aware that would be the case, and I found it upsetting because you get to know these people very intensely, and when you chat to them they all seem committed to the programme, but because it was not residential, we were going home every night, the pressures were immense and one by one they would just not come back. There were about 12 people there when I started, and of those 12 I think only two of us got to the end, the others either dropped out or they were kicked out, because it’s bloody tough.

The AA 12 Steps recovery programme also played a part, but you personalised it.

I’ve got a lot out of AA, and I’m very cautious about saying anything that criticises AA because it might be something that I return to more rigorously at a later stage. I don’t go to meetings now as much as I used to in the first year. I would say I’ve got tools from the 12 Steps rather than it being something that I live my life by, which is slightly different from what you might hear other people say. But all the stuff that’s in the book, the alternative interests and lifestyle that I found, as well as the writing itself, has helped me stay sober. If I think about having a drink, I remind myself I’ve written a flipping book about staying sober, so at the least it would be hypocritical – and that’s a massive motivator. So I’ve found my own path, but I certainly don’t want to dismiss the 12 Steps.

The religious element of the programme wouldn’t have been helpful to you, and you say you had problems with the meditation part as well, instead replacing that with a kind of thirst for knowledge and experience.

Actually in recent months I’ve been trying more meditation, but for me walking along the coast rather than sitting still was a more productive kind of meditative practice.

When you returned to Orkney, were there particular discoveries you made that stick out? The Fata Morgana phenomenon, for example?

For some reason there are some bits of information, as soon as I hear them I think, “That appeals to me, there’s something about it that’s kind of my thing,” and these different types of sea mirage, and learning about them and really understanding the scientific explanation behind them, I don’t think removes the magic. The Fata Morgana and the sea mist mirages, also tied in with the myth of the vanishing islands and Hether Blether became a way of looking at the part that drinking played in my life: a kind of false promise, the island you will never reach. And understanding different types of cloud, reading about noctilucent cloud and then realising that I was in the right place at the right time – at midsummer on either side of midnight, out and about in the countryside – that I might see it. And then eventually seeing it and knowing indisputably that what I was seeing was what I’d read about. Putting the book-learning and real-life experience together is quite thrilling.

Even though I am swimming in the sea and walking on the coast, I’m spending a lot of time on a laptop, and there’s wonder in networks of information and the logistics of transport as much as in migrations of birds.”

And you stress how technology plays a big part in that, and accompany that observation with some fabulous imagery, like when you compare global transport logistics to a flock of starlings.

I quite like that sort of juxtaposition of, say, nature and the internet, or unexpected images. It feels fresh to me, and kind of appealing to my own style of, I suppose it’s nature writing but with my own edge. I wanted to write about Orkney and the magic of it, but in a real, modern context, and to not deny the fact that even though I am swimming in the sea and walking on the coast, I’m mostly spending a lot of time on a laptop, and there’s a kind of wonder in the networks of information technology and the logistics of transport as much as in migrations of birds.

You list your post-rehab ‘cross-addictions’ as “Coca-Cola, smoking, relationships and the internet”; and there’s also that chasing of the buzz with windy walks and icy dips. Are all those impulses as strong as ever? You’re drinking tea right now, not Coke…

But earlier on I was drinking Coke. I usually drink Coca-Cola at the same time as smoking, and when I’m writing as well. Yeah, relationships – but I don’t want to talk about that one just now – and the internet are all still things that I have to watch. Because I’m aware that I get a buzz off internet approval, that doesn’t mean I shouldn’t do it entirely. It’s just about self-awareness, I suppose.

The harsh climate on Orkney and the atmospheric conditions there are woven into local myth and folklore, which you also weave into your story, but you don’t sentimentalise island life. This is a tough environment all year round, typified by strong winds and huge waves smashing into the cliffs.

Some days it can be flat calm, it’s very changeable, but the farm looks over the bay to a headland where the cliffs are maybe 60 feet high, and in a westerly gale on the roughest days the waves can come right over the top. And there are no trees on the farm because of the salty, windy conditions, and stuff just rusts there. I quite like the wind. Now if it’s a windy day in London it makes me feel at home. Rain and drizzle I’m not so keen on, but the wind I can cope with, I quite enjoy it.

Those conditions are helping to regenerate the local economy. What are your feelings about the changing landscape and seascape with all the wind, wave and tidal technologies that are being introduced?

In general I’m in favour of the new renewable energy industry in Scotland and in particular in Orkney. We’re using power, and it’s obviously better if it comes from these sources rather than fossil fuels. But even since I wrote the book there’ve been a lot of changes. The development hanging over the farm has now been kicked into the long grass, and there are concerns that the renewable energy industry in Orkney is not going to develop to quite the scale it was perhaps hoped, for a number of reasons. Firstly the devices that they’ve been testing for many years, a lot of them aren’t quite getting to the commercial standard that’s required – because of the huge power of the sea. They’re using Orkney as a test ground because it’s got these big forces, but the same forces are actually destroying the machinery. A lot of money and effort’s been going into these things, and some of them are still being tested, but a couple of companies have run out of funding, and a couple have moved out of Orkney and continued their operations south. The other thing is that Orkney is now producing I think 105% of its own electricity through renewable energy, which is great, mainly onshore wind, but in order to export this, what’s needed is a new link to the grid, which is a vastly expensive project and at the moment is a huge political issue. The money has not been put up for that yet, so the future is uncertain and maybe looking a bit less hopeful than it was. I’m in favour of all this stuff, but I find it emotionally upsetting that this development would go on the very stretch of land that gave title to the book. But it looks like it might well not be happening now.

Your summer job with the RSPB resulted in a memorable encounter with a corncrake. The story of this bird’s near-extinction is a cautionary tale of our lack of mindfulness. The birds meet a gruesome end when they are rounded up in the centre of a field at harvest time and caught in the blades of the mower.

Because I’m a farmer’s daughter, I see both sides. I’m not too misty-eyed about it, but it’s obvious that the demise of the corncrake is due to agricultural practices, and bigger and bigger machinery and with less and less uncultivated land in between. None of the farmers I speak to want to kill the birds, and a lot of them are very knowledgeable and enthusiastic about the wildlife on their farms. I’m cautious about what some people in conservation see as a battle between agriculture and maintaining habitats. It’s the farmers who actually care for the land a lot of the time. But in the particular case of the corncrakes agriculture and human activity have caused their demise. A lot of money and effort has been put into the corncrake conservation programme in Scotland, and I think that’s fair enough because it has been in such a short time that the numbers have declined.

But there is such a practical and easy solution, of just cutting the crops in a different way.

It certainly improves the chances for the chicks, but it’s quite easy to read about these things and say this is what you should be doing. When you go to a farm and see how it’s all set up, it’s always more complicated. But I would say almost all the farmers, when we found the corncrake on their ground and I spoke to them, with the small amount of money that we offered them, they changed their mowing patterns. The other option was to delay the date of the mowing, which is a much bigger consideration, particularly in Orkney where the summer ends quite quickly, it would risk getting the crops in at all, and certainly risk the quality of the crops. So on the off-chance that there might be one bird in that field, the farmers can’t necessarily see the benefit of that at all, which I have some sympathy with.

Would you have been able to overwinter on Papay without the writing bursary from Creative Scotland?

Actually the first winter I went there it was an unexpected tax rebate, together with cheap lodgings in an RSPB cottage that’s usually empty in winter, that allowed me to do it. I was there for two winters, and in the second year I got money from Creative Scotland to work on my edit. The RSPB actually upped the rent the second winter so I needed a bit more money. I live very cheaply, but I needed the bursary in order to do it, certainly.

And how did you find the editing process?

Well I find writing anguish, I find it very difficult, but at the same time it’s all I want to do. I felt very lucky to have the time and space to be doing this. I had a picture in my mind of the overall project, but on a daily basis was figuring out the practical things I needed to do to make that happen. I don’t find it easy but I was very strict about sticking to my word counts and redrafting targets. I’d usually redraft one chapter a day or something like that, and then each draft I dragged it through, it improved. Then I had lots of different bits and pieces that I could slot in, notes on my phone, different processes of both using printouts that I wrote over and typing on the computer.

Where have you been living, and what have you been writing since?

When I left Papay, I stayed in Stromness for a summer, working again for the RSPB, and it was back in Stromness that I got the book deal. I was thinking of coming back to London, but I had a friend who lived in Berlin who said come over. I wanted to go back to a city and Berlin is a lot cheaper, so I ended up being there for a year. I’d missed city life a bit, particularly the peer group of other people doing similar creative things, or writers about my age. There’s an artistic community in Orkney, but they tend to be older generation – and also it’s not the easiest place if you’re single, especially on Papa Westray. So I went off to Berlin for a year, then I returned to London to be here for when the book came out.

So how did you find the nature around Berlin?

Firstly it’s an incredibly wooded city with some great parks, and I got interested in watching the birds in the parks, particularly birds of prey. I wrote a thing that’s in the Guardian about looking for goshawks in Berlin. There are about a hundred pairs living in and around Berlin, which is amazing. Also Berlin is surrounded by forests and lakes, completely different terrain than I was used to, and I went out a few times camping with a friend and heard the booming bittern and watched the cranes flying over. I’d become familiar with the seabirds of Orkney, so it was really refreshing to explore new territory. I’m a novice birder, but the RSPB website’s brilliant, it’s got little sound recordings of the calls of all the different birds. It’s always this cross-referencing thing with books and then real life, and you only have to do it a few times and then you’re kind of, “I’m a bird nerd now.”

So now you’re back in London, how are you going to get your swimming and nature fix?

It was quite a quick decision to come back, but I’ve started looking at the map and here in East London there’s Epping Forest, which is kind of edgelandy and has a lot of interesting links to London history as well, so I’m going to be doing a bit more exploring there. And I can swim in London Fields lido, which is outdoors but very luxuriously heated. But I miss the sea, and I don’t imagine I’ll be here forever.

What have you been writing since finishing this book, and how do you expect the next one to take shape?

I write a diary every day, so I continue that, and I’ve been writing about the moon – a few things have appeared online – and I wrote this quite long essay about going to Berghain, the famous techno nightclub in Berlin, which is a kind of extended metaphor about nightclubs and techno clubs in particular and under-sea creatures, and parallels between the dissociation of diving and of being on drugs. I’m working on something about traffic islands at the moment as well, so I have a number of different subjects. I think book two will continue in non-fiction mode in a similar tone of voice, but with a kind of expanded subject matter but probably still quite a lot of my personal experience, because I think that’s just what I do. It might be a collection of essays, I don’t know…

Of course some of these chapters began as essays.

That’s right, and then my own narrative is what linked them. So I’m not quite sure yet, but I’ve certainly got some places that I’m going and am excited about.

Have you been able to listen to all the Book of the Week recordings?

Good question, this is the kind of stuff that’s on my mind at the moment. I have listened, and I found it extremely strange. It’s highly abridged and the abridger is very skilful in how she’s done it, I’m glad I didn’t have that job myself. I know another writer whose book had been on it and he was quite pleased with how they’d abridged it and everything, so that gave me confidence, and it’s really, really great but it’s just very weird. Especially the first episode, which lumped together a lot of the biographical information that was needed to set up the rest of the book, which was very intense and quite hard for me to listen to. Episode 4 was my favourite, it was a lot of the internet stuff and then a little bit of the sea-swimming, and I was pleased with the selections that they made. It’s very interesting, the whole process.

How have your family responded to the book?

Very kindly and supportively and generously. It’s unchartered territory for all my family. This last couple of weeks the book has got much more attention than I ever imagined, which is very pleasing but it’s strange, and there’s a vulnerability involved in that. My dad posted a thing a couple of nights ago on Facebook, saying that he thought my account was fair and true, and that he was pleased for me. It was quite a relief to read that, because I have been feeling a bit of responsibility. So I’m very grateful to them. My relationship with both my parents has improved a huge amount since I got sober, and continues to do so.

Coming out of the whole process, does Orkney feel even more like home?

Absolutely it does. The three years I was back, I lived in Orkney as an adult for the first time, and things that might have mattered at school about not being Orcadian didn’t seem to matter anymore. And I realised how lucky I was to have this place that I can go back to and have links to. But then here I am back in London. So it’s complex still, my relationship with the place, but it would be easier for me to go back and live there now.

Finally, is there a single piece of advice you’d give to recovering addicts?

Give it time, I suppose. It might feel like crap and it’s always going to be hard, but I think if there’s a message in the book it’s about allowing the unexpected. It’s a process of healing. Give it time and look after yourself at the beginning, and really anything can happen after that.

Amy Liptrot’s writing has appeared in the Guardian and various magazines, journals and blogs. Some of the chapters in The Outrun emerged from her regular column in Caught by the River. Aside from helping out at the family farm and conducting fieldwork for the RSPB, she has worked as an artist’s model, a trampolinist and in a shellfish factory. The Outrun is published by Canongate in hardback and eBook, and was shortlisted for the 2016 Wellcome Book Prize. Read more.

Amy Liptrot’s writing has appeared in the Guardian and various magazines, journals and blogs. Some of the chapters in The Outrun emerged from her regular column in Caught by the River. Aside from helping out at the family farm and conducting fieldwork for the RSPB, she has worked as an artist’s model, a trampolinist and in a shellfish factory. The Outrun is published by Canongate in hardback and eBook, and was shortlisted for the 2016 Wellcome Book Prize. Read more.

wellcomebookprize.org

amyliptrot.tumblr.com

@amy_may

Author portrait © Lisa Warna Khanna

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista