Another side of Borges

by Norman di GiovanniWe would begin our stroll down the Avenida Belgrano, a wide, busy, modern thoroughfare, trying to speak over the roar and fumes of the traffic. The ubiquitous snub-nosed buses crawled along in step with us, throbbing and belching their murderous black exhaust in our faces. Borges never seemed to notice. He was too busy discussing the word music of Dunbar, Coleridge, or the Bard himself.

The avenue had been built in fairly recent times during a programme of street widening, which meant the demolition of houses on either side of the earlier roadway. Parallel to the avenue, two streets to the south, was Calle México, and there, between Bolívar and Perú, stood the National Library.

To escape the bothersome traffic we had the choice of crossing Belgrano and cutting south either one block to Venezuela or two to México. These streets might be lined tight with parked cars but they were relatively peaceful.

There was a stretch of México that consisted of old-fashioned two-storey buildings with balconies that teemed with people, plants and drying clothes that were draped over their balustrades. The buildings might have been boarding houses. Across their fronts ran untidy ropes of electric and telephone cables. It was a humble neighbourhood of rundown shops and dingy bars.

In the immediate vicinity of the Library industrial goods such as heavy-duty pumps were displayed in the shop windows. The only trouble with making our way on these back streets was the narrowness of the pavements; the two of us could not comfortably walk abreast, which meant that with Borges clinging to my arm I had to proceed half a step ahead of him in a crabwise manner.

It was in the course of these daily walks that Borges gossiped to me about all and sundry – and it was not always benign. One day it was the turn of novelist Ernesto Sabato, whom Georgie dubbed the Dostoyevsky of Santos Lugares (the out-of-town suburb where Sabato lived) for his bouts of melancholy. Borges chuckled over a story told in solemn seriousness by Ernesto’s wife Matilde. She had accompanied her husband on a flight to the interior, where Sabato was due to give a talk. When the plane landed it became Matilde’s painful duty to inform the puzzled reception committee not to approach her husband. “Ernesto,” she told them, “está en un pozo de melancolía.” Ernesto’s in a pit of melancholy.

I got my oar in. I told Borges about the time I was strolling down Calle Florida with Ernesto and Matilde. Matilde was proselytising me. To prove her husband’s worth and standing as a novelist she drew from her handbag a sheaf of reviews, some in French, and began reading them aloud to me.

Georgie might have a go at Victoria Ocampo, ‘Queen Victoria’, belittling her for her ignorance of printing procedures. He said she would ask why, when space at the end of some page or other of Sur had to be filled, they couldn’t just stretch lines of type as if they were made of rubber. I suspect that Borges as a young man had been very much in awe of Victoria and her imperious and dashing bohemian ways. Perhaps he’d had a secret crush on her. She was rich, aristocratic, chic, exotic. She had taken the writer Eduardo Mallea, some thirteen years younger than herself, as a lover. Mallea became a novelist with an international reputation while Borges was struggling to write his difficult early stories. Mallea’s reputation eventually went into steady decline; Borges’s grew. Mallea used to invite me to tea in cafés along Corrientes to express his total admiration for Borges and his work. All Georgie ever said to me about Mallea was that he had a touch of the tar brush.

At the Library we shuffled through the revolving-door entrance and up the grand marble staircase, entering first Borges’s outer office with its scruffy, bare, wooden floor. It was here that the secretaries huddled at a tiny table in a corner by a window. Except next to that window, the room was lightless, bleak and spartan. A small wire wastebasket stood beside the table. There was one telephone – big, clumsy, black, its cord frayed. It didn’t matter. The phones, like the secretaries, only worked part-time.

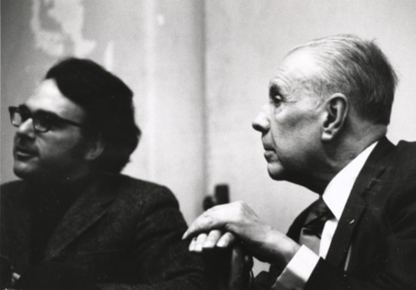

Norman di Giovanni with Borges, c. 1970 (photographer unknown)

The building dated from 1901 and had been, as Borges was fond of telling visitors, the seat of the national lottery. On the stairway, replicas of the lottery balls were worked into the balustrade. Borges would tap them with his stick.

The inner sanctum, his office, had a very high ceiling, green wallpaper printed with bamboo-like fronds, polished mahogany panelling, and a parquet floor. We worked at a massive old-fashioned conference table in the centre of the room. At the far end was the desk that Paul Groussac, a distinguished predecessor who also ended up blind, had had built to his own design. It was U-shaped, with strange drawers and odd compartments. If you sat behind it as Borges never did, the desk surrounded you. There was something both gloomy and sinister about such a piece of furniture.

The room’s other furnishings were a couple of revolving bookshelves and a tall set of drawers where Borges slipped the drafts of poems he dictated in the mornings to one of the secretaries. Two pairs of doors led off the room straight onto a corridor. These we used only when trying to avoid someone who might be waiting in the outer office or when we went to the vast, stark loo that was used only by us. Sometimes Borges, who was shy about his false teeth, would take them out here to rinse and would say to me, “Don’t look now.”

Next door was the room Groussac had died in, a detail Borges took ghoulish delight in recounting, for once upon a time the director had lived on the premises. There were traces of a kitchen that proved it. But Elsa would not hear of making a home in the Library. It was a gloomy place, and there were times when I thought I too would go blind there.

On the main table where we worked lay a dictionary of the Spanish Royal Academy, the smell of whose paper and binding Borges and I were fond of savouring.

In the outer office visitors waited to be announced by a secretary. One day the secretary told Borges that Jean de Milleret was there to see him. Milleret was a Frenchman who lived in Buenos Aires and was well known to Borges. He had conducted a book-length interview with Borges in French, and the volume, Entretiens avec Jorge Luis Borges, was published in Paris in 1967. Now the book had been translated into Spanish and had appeared in Buenos Aires.

In an uncharacteristic outburst Borges came near to shouting. “I don’t want to see him; tell him to go away.”

When he had calmed down a bit, I said, “What was that all about? Didn’t you do a book of interviews with him?”

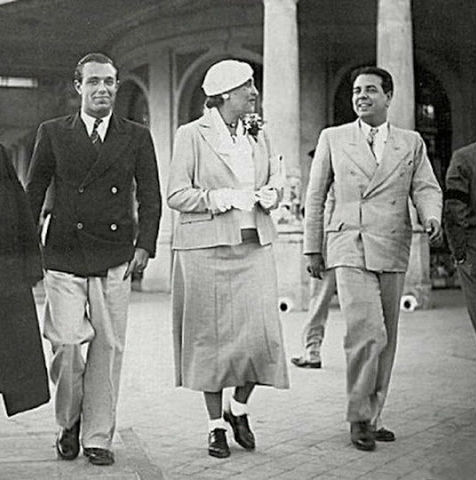

Adolfo Bioy Casares, Victoria Ocampo and Borges on la Rambla de Mar del Plata, Buenes Aires in 1935. Wikimedia Commons

“Yes,” said Borges.

“And?”

“Well, he made me say unfriendly things about my family,” Borges said.

“Made you say? Did you say those things or not?”

Borges went sheepish. “Well, yes, but I never thought the book would make its way back to Buenos Aires.”

The secretary came in to say that Milleret had left. She placed on the table a copy of the interviews in French, with numerous inked in corrections, that Milleret had been there to deliver. On the half-title page he had written the words, “Au Maître d’oeuvre en témoignage d’estime, de compréhension et d’amitié.” What about the Master’s esteem, understanding, and friendship for the Frenchman? Evaporated without a trace due to no fault of Milleret.

Borges handed the book to me. “You have it,” he said.

Sometimes Borges and I wandered around in the Library’s basement stacks in search of a book. The place teemed with cats, whose job it was to keep down the mouse population. They did, but the price was an overpowering stench of feline urine.

We might turn a corner of this labyrinth of shelves and surprise a small knot of employees who were gathered round drinking maté. When they saw it was Borges – or even me if I were alone – they lost no time bowing and scraping. Their embarrassed actions suggested they were doing something illicit but, if they were, Borges could not have cared less. Here underground the Library’s books were arranged by their size, not subject, in order to have uniform shelf heights. So a book on geometry might rub shoulders with a volume of Virgil or a French poet or a treatise on Celtic mysteries – so long as all three measured the same height.

These vaults were not without their occasional bookish adventures. Late one afternoon the sky went black, and there was a calamitous thunderstorm such as those you never see anywhere but in Buenos Aires. In the blink of an eye the streets were swollen rivers. This storm was accompanied by a power failure, so that suddenly we were without electric light. After a time, when the rain had abated, everyone – readers and staff – left the building. Borges and I needed a volume of Victor Hugo in order to finish an article for The Book of Imaginary Beings. The watchman lent us a weak torch that allowed us to prowl the stacks looking for Hugo’s poems. Victor Hugo might have been anywhere among the Library’s holding of 800,000 volumes, but Borges and I were not deterred. We started out in the dark in search of our book. Something made us inch through the first-floor stacks and start for the next level. Ahead of us the stairway split, one branch curving round to the right and the other to the left. Something impelled me to the left. When we reached the head of the stairs I was forced to pause for Borges, half a step behind me, to catch up. As I did so, the beam of my light came to rest on a set of Hugo’s complete works.

“Isn’t this a stroke of luck?” I said.

“I think we’d best be leaving with our book now,” Borges answered. “The word for this is uncanny.”

A door or two away along Mexico Street from the Library was the headquarters of the Association of Argentine Writers, always referred to by its Spanish acronym, SADE. Its building was one of the city’s few structures still standing that dated back to colonial times. This made it a favourite of Borges’s. A single storey tall, it had a flat roof with a masonry balustrade on the street side like the kind Borges’s artist sister Norah was fond of depicting. You entered it from the street through a wide arched doorway called a zaguán. A coach and horses would once have driven in and out of here. The driveway led a long distance straight through into the interior of the house, and along it were a series of patios, usually three, onto which the rooms, with their galleries, opened. The first patio had a well head to hoist water from the cistern below. Throughout the house the windows were grilled. Servants were housed at the rear, and grape arbours shaded the patios. Borges had often written about these black-and-white chequerboard-tiled patios. The place had a welcome sleepy peacefulness about it. Some Spanish documentary filmmakers once shot Borges here in one of the rooms, rocking back and forth in an old chair.

It was to a front room of this building that Borges asked me to accompany him on a certain winter’s morning. The occasion was the wake of his one-time close friend, the poet and novelist Leopoldo Marechal, from whom he had been estranged for many years. Marechal had published a novel in 1948, Adán Buenosayres, in which Borges figured as one of the protagonists. But the split with Marechal was not over that and had taken place considerable years earlier. Alas, they had fallen out over the issue of Peronism.

Marechal looked small lying there in his open coffin. Borges stood by the side of the corpse, contemplative, for several minutes. He then made his way to speak a few words with one of Marechal’s daughters. When we left and were back out on Mexico Street I could see that Borges had been moved and was distressed and saddened to see the dead man. It seemed to be one more instance of the long shadow of Perón come to haunt him.

It was always a source of amazement to me how little Borges was able to understand the lives of ordinary people – how infrequently he emerged from his shell to show sympathy with others.”

Borges’s secretaries were friendly and loyal. They were unfailingly considerate of me because they knew that we were all on the same side – Borges’s. They were serious in their work, unpretentious in their manner, and probably not highly educated. One of them entered the office one morning, and it was obvious that she had been crying. She had come to tell Borges about the cadete. The word cadete in the lingo of Buenos Aires meant a messenger boy, an errand boy. Every office had one. They usually wore some kind of uniform.

The Library’s particular cadete was a small man, brown as a nut, with receding hair. He was serious and unfailingly polite. I think he was much younger than he looked. The secretary wanted to tell us that after an absence of four or five days, the cadete had died the night before. This was unimaginable, for the man had always seemed in good health.

“You see,” the secretary explained, “he lived in a villa miseria on the outskirts of town. His tin shack had no running water or proper sewage. He had a family, and what with payments on a television, a refrigerator, and so on, he had worn himself out trying to make ends meet.”

Borges turned to me after the secretary left the room. His voice had a register of sympathy in it that I seldom heard from him.

“Look at that, di Giovanni. The poor fellow was paying for a refrigerator and television. I don’t understand why the working man isn’t content just to read his Shakespeare or his Dante.”

It was always a source of amazement to me how little Borges was able to understand the lives of ordinary people – how infrequently he emerged from his shell to show sympathy with others. We knew a poet named Arturo Cuadrado, an exile from fascist Spain. Along with many of the Spanish Republican fraternity, Cuadrado haunted the Avenida de Mayo, and every once in a while Borges and I ran into him on the street. Because of Borges’s blindness, Arturo would approach and always introduce himself in this way: “Soy yo, el poeta, el español.” It’s me, the poet, the Spaniard. There was a gentle sweetness about this, and the words never failed to amuse Borges. He often repeated them to me, not cruelly but in fun, slightly mocking Cuadrado’s tone of Spanish pride and including the Spanish lisp in the last word. One day on the Avenida Cuadrado approached, all sadness and despondency. He told Borges he’d just had news that his mother had died in Spain. When Arturo left us, Borges turned to me and said, ‘”You see, di Giovanni, to us he was always an object of fun, but here he is now, a flesh-and-blood man suffering.”

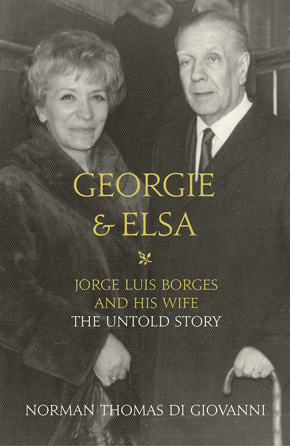

From Georgie & Elsa: Jorge Luis Borges and His Wife – The Untold Story.

Norman Thomas di Giovanni worked with Jorge Luis Borges in Cambridge, Massachusetts and in Buenos Aires from late 1967 to 1972 and thereafter sporadically until Borges’s death in 1986. In Georgie & Elsa he draws on his extensive collection of diaries, notebooks, letters, manuscripts and photographs, most of which has never before been seen, to provide a unique insight into one of the few true geniuses of literature at the time of his short and tempestuous marriage to the recently widowed Elsa Astete Millán. Georgie & Elsa is published by The Friday Project.

Read more