Ayelet Gundar-Goshen untamed

by Mark ReynoldsAyelet Gundar-Goshen’s debut novel One Night, Markovitch is a dazzlingly funny and tender story about love, betrayal and mythmaking. Set before, during and after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, it centres around an unremarkable man who agrees to an arranged marriage to a beautiful woman to help her escape Nazi Europe for the emerging Jewish homeland – and falls instantly and hopelessly in love. It’s also the story of larger-than-life war heroes and the dubious fables that are built around the birth of a nation, and a vivid celebration of human passions and untamable nature.

MR: A real-life incident regarding a broken arranged-marriage contract sparked this novel. How did you come across the story, and how long did it linger in your mind before you knew you had to write it up?

AG-G: I was visiting my partner’s parents’ house, I think it was maybe the first time. They live in a village and behind their fence I saw this house that had a strange atmosphere about it. I asked who lives there, and they said “Beautiful Bella”, and they told me the story about this beautiful, miserable woman who had been married to the most awful man in the village. He was already dead by then, but I was drawn to the idea of the whole village keeping his story alive. I mean, this woman is 80 but they still call her Beautiful Bella, and the man is dead but they still talk about what an evil man he was. And I thought, well, if they keep it going for so many years there must be something in it. I asked a bit more and got to know about this whole operation of fake marriage, which really happened. They really sent people from this specific village and the areas around to Nazi Europe to get women out, and there really was this man who came back and refused to give a get [divorce document]. So that’s how I ran into the stories.

But you don’t paint Markovitch as a villain at all.

No, that was very important to me, because the story stops very soon if he’s just a villain, it’s just a kids’ tale about this really, really bad man holding this really, really good woman. This is boring. At first I thought maybe it would be her story, but then I thought he’s the one who’s making the choice here, and I wanted to go under the skin of this man that the whole village really hates, and to tell the stories from his point of view. So it was really important for me for him not to be the bad guy, and to realise how regular people do bad things. I’m always fascinated by that.

He’s beyond regular though, isn’t he? He’s nondescript.

Yeah, I like the idea of describing the nondescript. In Hebrew there is this poem from the independence war, saying something like “And we’ll remember them all, the beautiful men with their beautiful hair and their beautiful figures.” And I always thought, well, people died in this war who weren’t beautiful, aren’t we supposed to remember them too? So it was about these people who were in this heroic time in history but weren’t heroic, they were just people like you and me.

Markovitch’s best friend Zeev Feinberg is the polar opposite: the flamboyant and vibrant heart of the novel’s opening, a legendary war hero whose womanising and other faults are forgiven with a twitch of his magnificent moustache. But despite all the joy and sensuality surrounding him in the first part of the book, we slowly come to realise that the kind of one-sided mythmaking that Feinberg and the resistance leader Froike represent is a fragile foundation on which to build a new nation.

Mmm, hmm. These powerful, macho figures that are easy to fall in love with steal the focus from Markovitch, which is exactly the story of his life. This is the story of Markovitch but we much prefer being with Feinberg, you know, sleeping around with all the women. This always happens to Markovitch. And I think this machismo can work up to a certain point, but it won’t take you any further, and then you start to realise that there is a cost to being so brave all the time. You pay something, and this something is part of your own self-knowledge, of the other aspects of humanity that you have in you and you never meet because you’re too busy being a hero.

Can you say a little about the aims and activities of the Irgun in the battle for independence?

Well, first I’ll make a distinction between the literary freedom I took and the historical background. The British were ruling the country back then so Jews weren’t allowed to have an army, but everybody knew that the British Empire was going to withdraw at some point in time, and they knew that the Arabs also had militias, so they made their own militias, and there were three different kinds: the Haganah, the Etzel and the Lehi. The radical militias made terror attacks against British officers in Mandatory Palestine, while the Haganah tried to work with the British. You had Ben-Gurion, and his famous quotation saying “We will fight Nazi Germany as if there were no British, and we will fight the British occupation as if there were no Nazi Germany.” But for my generation this whole distinction between the different irguns – ‘irgun’ means a fighting militia – the distinction between them, which was very, very important for my grandfather’s generation – like back then they wouldn’t sit next to each other at dinner, they wouldn’t talk to each other, every militia really hated the others, they were fighting each other more than they were fighting the British or the Arabs – but after a while the colours just melt into each other. So if you ask a teenager today, they wouldn’t know which irgun it was, they would just say, “Ah, the Irgun.” So the further you go from real history and facts, it becomes more of a tale, more of a once upon a time.

The ink-drawn national flag of Israel is raised at Um Rashrash (now Eilat) across the Gulf of Aqaba on the northern tip of the Red Sea. Israeli Government Press Office/Wikimedia Commons

This is a time of daring adventure, sexual freedom and strong passions, but beneath the surface the novel also zooms in on personal fears and uncertainties, the most significant being Markovitch’s resolute but desperate hope that Bella will grow to love him. A review in Haaretz suggests the book “hypnotises the reader with the possibility that if you truly desire something for long enough, it will be yours. Yet because it is premised on unrequited love, the novel also equates Zionism with a mad ardour and selfishness.” Would you go along with that?

Yes. This is just one part of the book but I think there is something in Markovitch’s obsession with Bella that for me echoes some of the obsession of certain aspects of Israeli society towards land, towards territory. The idea that if you hold onto something long enough it will be yours – which is very romantic in a way, but it’s also a very violent and blind idea to think that you can hang on like this for ages. I won’t say that this is the only aspect that exists in Zionism, but I would say that this is something Markovitch’s character echoes.

The main characters are all European Jews newly arrived in Palestine. The Arab locals are seen only as an obstacle to be removed or killed, but there is also no interaction with Oriental Jews. How long would it be before these two groups would assimilate? Or was that already happening beyond these characters’ eyeline?

In Israel at that period in time, you had Jews that came before the war, who were deep inside the country, you had Jews that came after the war, the Holocaust survivors, and you had Oriental Jews coming to Israel not because they’re escaping something but as a positive choice. Most of the European Jews didn’t come out of ideology, they came because they didn’t have any other choice. It is the Oriental Jews that were truly Zionist, they really left something good behind them in order to get to Israel, where they were greeted with so much racism. They spoke Arab languages, which were considered the language of the enemy. They got the bad jobs, when lands were let to people they didn’t get the rich areas, but were shoved into the corners. And it took a long time before you had Oriental Jews as officers in the army, or in the university as professors. There was a lot of discrimination. It started changing in the 70s, when the Black Panthers were demanding that Oriental Jews get just as many places in the university or jobs or budgets as the European Jews. But it’s still a struggle in Israel to this day.

But such specific historical detail is not dwelt on in the book. This could be any war in which heroic deeds sit side by side with the occasional requirement to point guns at women and children. Why was it important to punctuate the picaresque levity with some very disturbing scenes?

I feel that literature is not about having somebody cuddling you on the sofa, sometimes it has to be about punching you in the stomach. When I started writing it I was really trying create a kind of carnival, something very sensual and very alive, because this period of time really was a kind of mythological carnival. Everything is changing. All of Europe is changing. Everybody’s on the move or shooting at each other. It was the best of all times and the worst of all times. I always had this feeling that the birth of a nation was a womb of blood and fire. So at first I really enjoyed writing it, but then you stop for a moment and you think, this is a war we’re talking about, and this country, this new thing, this new creature that just came into life, it came into life on the back of other people whose dreams of a country weren’t fulfilled because their territorial expectations weren’t the same as ours, and I really wanted to have both sides. I didn’t want to miss the comic part or the tragedy.

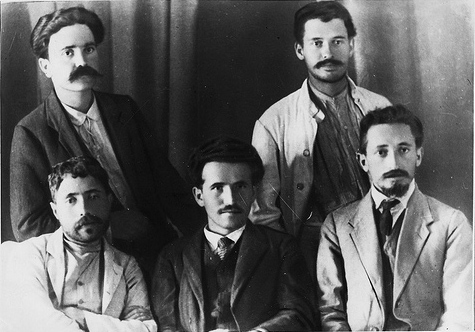

A youthful David Ben-Gurion (centre, seated) compares moustaches with Zionist leaders and writers (clockwise from top left) A. Reuveni, Ya’akov Zerubavel, Yosef Haim Brenner and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, 1912. Wikimedia Commons

You’ve said that Feinberg is partly based on your grandfather. Does that include the twinkle in the eye and the expressive moustache?

The moustache, definitely. There was something about my grandfather and his whole generation, at least in elementary school, these were our superheroes. Today I might be very judgmental or critical of how we were taught, but as kids we really looked up to these people. They fought the war and we were really proud of them, and then when we grew up we found out that our heroes did things that we’re not proud of. It’s a very difficult moment. When you realise it about Batman or Superman it’s one thing, but when you realise it about your grandfather that’s another.

To what extent has your study and practice of psychology informed your writing?

I don’t think I’d have been able to write this book without thinking of it from a psychological level. Even though I wanted to have this odyssey, going from Palestine into Europe and then from Europe into Palestine, and the odyssey across time, I still wanted it to be a basic love story, and a basic story of the obsession of a man with a woman, and in order to do that, in order for him not to be the villain, then you have to dive in. You have to be willing to let go of this part of you that’s always judging people. You know, you hear about a man holding a woman against her will and you say, OK, so he’s an asshole. But when you’re a psychologist you don’t have this privilege. If he entered your clinic, you wouldn’t say, “Are you an asshole?” You say, OK, now I have to find a place within me that could do the same thing. Otherwise I’d never be able to either help him or write him. My favourite novels as a teenager, like Lolita and Crime and Punishment, are about the protagonist doing something you would want to condemn and then forcing the reader, instead of condemning, to identify.

You also studied screenwriting and have made short films and written for TV. Was that a good grounding for approaching the novel, or did the novel take a completely different set of skills?

Definitely very different skills from TV, because TV is something that you do for a living. I don’t watch television, I don’t like television, but I have to pay the rent. In TV you have to think about the audience all the time: how much reality can they take with their supper? In literature it’s the exact opposite, you simply forget about what anybody thinks, including your own family, and you just sit down and write, and this is a total commitment to what you believe is right.

A female officer of the Haganah gives a demonstration in the handling of a Sten gun during the War of Independence. Haganah Museum, Tel Aviv/Wikimedia Commons

East is East producer Leslee Udwin has bought the film rights to One Night, Markovitch. Are you working on the adaptation?

I’m involved in it. I wrote the first draft, but I don’t think I’ll be writing the whole way through because the moment you have a director they revise it, the closer they get to shooting it’s up to the director to make the final pattern. I laid the foundation, which is harder than writing the novel. Really.

So what had to give along the way?

It’s so different, it’s like meeting and trying to get to know another person. The basics of the plot are obviously the same, but you can’t do it the way you do with literature, because with literature when someone opens a door you can talk for five pages about all the doors that were shut in his face before, so that when he finishes opening the door you know exactly why he’s opening it in a certain way. But in film you don’t have this privilege of going backward and forward or to dive in and dive out, you need totally different mechanisms in order to pass on this information.

Do you have any sense yet how long it will be before the film goes into production?

Well they’re talking right now about shooting it next year, but because I’m part of this industry I know things can change very quickly. I can get a phone call saying it will be in half a year or in two years. It’s out of my hands now, and it’s down to many different people. I hope it will be fun. I’m also preparing myself for the possibility that I won’t like it, which is OK because even when you publish a novel you lose control over how people are going to read it, and what will they understand out of it. In a way it’s like taking the most intimate thing you ever did and letting go of it. And the film is just the same, that practice of letting go is important.

Poets have a hard time of it in this book. I’m thinking in particular of the father of Bella’s child, who is inspired by misery to rise from the status of a failed poet to a mediocre one. Why did you want to take a look at this kind of base level of poetic endeavour?

Like I told you before about the heroic figures leading me to want to know about the little guys, it was the same with poets. I mean, it couldn’t be that there were only the great poets, the famous poets that we still learn today in school, there must have been others that were just OK. And I thought, how is it to be an OK poet in the time of the great ones? So I really felt for him. The famous poets from that time are all streets today, and some of us don’t know any of the poems, but we know the streets, we meet people at Bialik, Alterman. I thought about somebody who doesn’t get to be a street but gets to be this little garden in one of the side corners, or a park bench.

There’s this factory of myth and you try to go behind the factory and look into the machines, how it’s made. How do you make a national poet? Male poets were highly appreciated because Hebrew was a dead language, it was just a language of the Bible. It was kept alive for 2,000 years because of praying, but nobody said “I love you” or even “Did you do your homework?” in Hebrew. They would say it in German or Arabic or Persian. When they came to Israel they had this huge mission of taking this language that was only preserved as dead or holy and making it an everyday language. Poets were the ones to make the language accessible to everyone, to portray everyday life, to write about love, to write about war and to have a Jewish culture once again – not just a religious one but secular too. So they were really, really important. But it was mainly men. You have female Hebrew poets from that period writing about very intimate issues. It was a mythological time, the great poets were writing about the war and the new Jew, and you have these really small poems where a woman writes about a tree. To this day you still have this segregation between Poetry and women’s poetry.

I try to avoid any separation between literature and poetry, or between the human and the earth, I like when it mixes, so you can have the sensuality or you can play with language, or with smells, it all interacts. Because I really believe that it does.”

One of the striking things in the book that many have commented on is the almost biblical language you sometimes use to describe the landscape and the weather.

There’s something about biblical stories, the density of it and the fact the whole world is alive and everything echoes everything. You really hear how the ocean sings to the sky, which sings to the man, which sings back to the ocean. They all talk and they all echo each other. If we’re talking about mythical times, there is something in this year of Israel’s foundation that I wanted to echo biblical times. Every word that we say today was written before in the Bible, was said before on this exact land, and stories repeat themselves. These are the rhythms, in a way, of this country, and I really wanted that to echo throughout the book.

And despite the bad luck that poets have in the book, it’s written in a very poetic style. Buildings, landscapes and objects are imbued with human senses, their mood shifting with that of their inhabitants, and characters are defined by aroma as well as thoughts and action.

I read Ovid’s Metamorphosis, containing all the different changing of forms like Daphne from a running woman into a tree. There was no separation between the poetic and the literal. I try to avoid any separation between literature and poetry, or between the human and the earth, I like when it mixes, so you can have the sensuality or you can play with language, or with smells, it all interacts. Because I really believe that it does. I’ll give you an example. I was walking in the street in Tel Aviv and there was this huge red sign of a cheap restaurant, saying “Two wings for 20 shekels”. And you stop, and you think, “This is poetry! You can buy two wings for 20 shekels, this is amazing!” And it’s just there, you know, in the street. You walk and suddenly look up from the really cheap restaurant, up to the sky, which is always there, and then you gaze back and keep walking.

What did Sondra Silverston bring to the novel with her translation?

Well, because I never read the translation – until a little bit today for the BBC – I can’t tell. I’m very rooted in Hebrew so all the literature I read is translated. My English is not good enough to enjoy literature in any other language. I didn’t read the translation because I don’t have the ability to know what’s good and what’s not. I really had to trust Sondra to take this and to make it hers and to find her own music, the music of the English language. I’m not capable of admiring her work, but everybody who speaks English tells me she did a really good job, and actually I decided I’m going to call her when I get to Israel and tell her that, because before I just said thank you in general because I can’t appreciate it, but now? Wow, thank you.

Which other Israeli writers do you particularly admire?

Grossman. I could tell you more, but it would be David Grossman, and Meir Shalev was very influential with his tone for this specific book. But when you ask ‘admire’ it would be Grossman. I think he’s the best Israeli writer, and the fact that he’s so politically committed is also something to be admired.

Are there also international writers who have influenced your approach to fiction?

Gabriel García Márquez, clearly, and Romain Gary/Émile Ajar, he’s a French author, he wrote The Life Before Us. Both García Márquez and Ajar write in a way that is both ironic and compassionate, and many times I think writers choose one path and ignore the other. Like Michel Houellebeqc’s irony and distance, for me it’s too far away. I don’t like eating cold food and I don’t like reading cold books. And then you have writers who are so alive and so full of compassion that you’re just drowning in it. But García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa and Ajar all have this sense of irony on one hand and compassion on the other, and I really try to steal from them and do the same.

You’ve published a second novel in Israel and now Germany. What’s it about, and when might we expect an English edition?

It’s very, very different from Markovitch. It’s called Waking Lions, it’s contemporary, the whole music of the words is different, but there is a certain similarity in the concept. It’s about an Israeli doctor who finishes a night shift and on his way back home he hits an Eritrean refugee and he leaves him there to go back to his wife and kids. The next day the refugee’s wife knocks on his door because she was there and she saw it, and she’s blackmailing him to give illegal Eritrean refugees medical help in the middle of the desert. So it’s completely different, but this is also a true story that I ran into, and it’s a story again about a regular guy doing this really bad thing. It’s supposed to be out here I think in 2016.

And what have you been writing since?

I’m working on my third novel right now. I don’t know how it is in the UK but in Israel it’s like when you’re pregnant, you don’t talk about it until the twelfth week after you run some tests and you know that it’s OK, that it’s rooted really deep, and I think it’s the same way with novels and it’s not the twelfth week yet, so I can’t say much about it.

Ayelet Gundar-Goshen was born in Israel in 1982. She holds an MA in Clinical Psychology from Tel Aviv University, has been a news editor on Israel’s leading newspaper and has worked for the Israeli civil rights movement. Her film scripts have won prizes at international festivals, including the Berlin Today Award and the New York City Short Film Festival Award. One Night, Markovitch, her first novel, won the Sapir Prize for best debut, and is now published by Pushkin Press. Read more.

Ayelet Gundar-Goshen was born in Israel in 1982. She holds an MA in Clinical Psychology from Tel Aviv University, has been a news editor on Israel’s leading newspaper and has worked for the Israeli civil rights movement. Her film scripts have won prizes at international festivals, including the Berlin Today Award and the New York City Short Film Festival Award. One Night, Markovitch, her first novel, won the Sapir Prize for best debut, and is now published by Pushkin Press. Read more.

Author portraits © Nir Kafri (above) and Alon Sigavi (feature image)

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.