Barbara Taylor: Out of the system

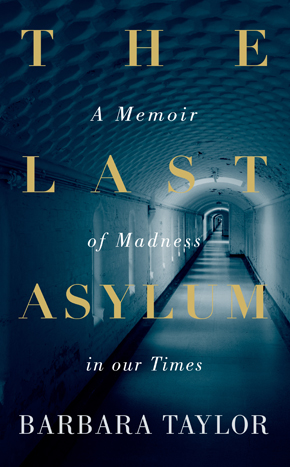

by Emma YoungBarbara Taylor’s The Last Asylum: A Memoir of Madness in our Times is a refined and beautifully written scrapbook of a study of the mental health system in the UK. It’s also Taylor’s deeply personal account of her breakdown and, ultimately, after many years of work and therapeutic support, her triumph over severe emotional illness. It combines this warts-and-all autobiographical material with the kind of research you’d expect from the acclaimed historian of Eve and the New Jerusalem and Mary Wollstonecraft and the Feminist Imagination. The latter was praised by Judith Hawley in the Guardian as an “outstanding companion to and commentary on” Wollstonecraft’s letters and a “product of many years’ engagement with Wollstonecraft”, so I begin by asking Taylor if that is perhaps a way into understanding the approach she took when it came to writing The Last Asylum.

“It really is like any other kind of research,” she affirms. “You take notes, and of course I had this source material to draw on, too… I suppose, in a way, I was like a different person back then.”

It barely needs stating: the bright, considered and articulate Taylor I’m speaking to today couldn’t sound more different from the distressed and distraught woman who inhabits the book. The “source material” she’s referring to here are the extensive diaries she kept during her 21 years of psychoanalysis, during which time she spent three periods in Friern Hospital (the former Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum) in north London following her breakdown in 1981. Taylor is extraordinarily open and frank in talking about this period of her life, and this personal insight makes the book incredibly moving. Talking to me, a stranger, about the intimate details of this period must be difficult enough, but writing and publishing the book for anyone and everyone to read is, I can’t help but think, incredibly brave.

So how does she feel about The Last Asylum being out in the world? Does she worry about readers judging her (current or former) self or trying to compete with her, and reviewers (such as Jenny Diski in the London Review of Books) doing the same? I imagine it must have been hard being both so frank and reporting others’ criticisms of her. She is, however, surprisingly enthusiastic about the reception so far and praises Diski’s review: “Jenny Diski wrote what some other people will probably think… It did take me by surprise when I first read it, but I also found it quite touching. I haven’t read what people have been writing online as I know that can be difficult to take, but I’ve read the media coverage, which has been extensive, and the reception has been very positive.”

Taylor achieves a finely-tuned balance between the autobiographical and the investigative, and to dwell on the former at the expense of the latter would do her considerable skills a disservice. The parts that particularly stick in the mind are the section in which Taylor reports Barbara Robb’s investigation into Friern’s treatment of elderly people “deprived of their teeth, glasses and hearing aids, and subjected to verbal abuse and physical mistreatment” in the sixties, and also the remarkable sense of community that these places could sometimes foster – with in-patients even running their own radio station at one time. I ask Taylor about her research process, and I’m curious about the material that she had to leave out. She describes trawling through archives, taking lots of notes, and some personal interviews that she conducted with mental health service users, although no former Friern patients. “I met some Friern patients but they were either unwilling or unable to be interviewed,” she tells me. This is surely one of the reasons a more extensive study of the institution/system hasn’t happened, but this doesn’t stop Taylor feeling disappointed, and, I get the sense, a little frustrated too – she sincerely hopes that others will capture more Friern testimonials before it’s too late.

Taylor achieves a finely-tuned balance between the autobiographical and the investigative, and to dwell on the former at the expense of the latter would do her considerable skills a disservice.”

Taylor’s analyst – referred to simply as ‘V’ in the book – comes across as provocative, shocking and even rude at times, and yet he was clearly hugely instrumental in her recovery: she praises the “’rites of psychoanalysis” as “containers for the uncontainable, solid supports for emotional chaos.” It’s a wonderfully evocative description that suggests both how desperate a patient entering psychoanalysis can be and how necessary a process it is for them. When I tell her that I didn’t much like V, she’s characteristically warm and self-deprecating, explaining that the comments which I find offensive are in fact direct interpretations of things she is saying to V: “the person that you didn’t like was me – a part of me.” She points out that by contrast her sister, on reading the book, thought that V had been incredibly patient with her. Taylor is adamant that psychoanalysis was a vital part of her care (which also included day centres, in-patient stays and therapy): “I may have had to stop private psychoanalysis if I hadn’t had the rest of the support, but I wouldn’t have survived without it.”

She wonders aloud at the lives lost to mental illness, and we end the conversation by talking about her hopes for the future of mental health treatment and frustrations with the current psychiatric support available. We talk about how she closes the book deploring the “care in the community” and “crisis teams, acute wards, recovery strategies, care plans…” which are not providing adequate care are in many places. She does not mourn the old asylums like Friern, which she says were dreadful in many respects, but she is angered by the deficiencies of the current system, quoting Costa Award winner Nathan Filer who recently referred to it as “an utter, God-awful mess.” She’s clear that she speaks only as an observer, neither a professional nor a current service user, “but in my opinion it’s bleak right now. We need more resources… we need centres based in the community with day and in-patient options… We need good employment training and opportunities… Above all, we need to listen to service users, and at the moment they aren’t being consulted.” Indeed, for those grappling with the complexities of our current system and plotting its future, The Last Asylum might be an extremely good place to start.

The Last Asylum is published by Hamish Hamilton in hardback and eBook. Read more.

Barbara Taylor‘s previous books also include On Kindness, a defence of fellow feeling co-written with the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips. She is a longstanding editor of the History Workshop Journal, and a director of the Raphael Samuel History Centre. She teaches History and English at Queen Mary University of London.

Barbara Taylor‘s previous books also include On Kindness, a defence of fellow feeling co-written with the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips. She is a longstanding editor of the History Workshop Journal, and a director of the Raphael Samuel History Centre. She teaches History and English at Queen Mary University of London.

Emma Young, a former arts publicist and literary night host, is a contributing editor and events manager at Bookanista. Follow her on twitter: @emmaryoung