Bit by bit by bit

by Ali BenjaminWhat happened?

Everyone asked the question, had been asking since the election. They asked while watching the news, that storm of headlines, jump-cut footage of marches and speeches and hand-sharpied cardboard, an endless, swirling blizzard – a siege, really – of protests and counterprotests, action and reaction, people screaming at one another in the street, neighbor versus neighbor, friend versus friend. (Or too often: friends no more. We were in new territory. People had their limits.)

What happened? Reporters asked it in small-town diners over $7.50 lunch specials, BLTs cut into neat wedges and Heinz bottles perched like microphones atop scratched Formica tables.

What happened? People asked one another in church basements, community centers, gyms, coffee shops, living rooms where they came together to weep, process, scrawl on placards, plan the revolution.

What happened? Parents snapped off NPR mid-story, not wanting to answer questions from the backseat. College students organized walk-outs, staged sit-ins, blocked freeways. A giant inflatable chicken appeared behind the White House lawn, some sort of protest that no one entirely understood. Everything was some sort of protest now.

What happened what happened what happened what

Everyone had their answers, and as is generally the case in these situations, everyone’s version of the story was a little different. It was impossible, it was inevitable, it was surreal, it was unreal, it was scandal, sea change, enthralling, a coup. It was some bad sort of smash-up: just the right-or-wrong elements at just the right-or-wrong time: anger, alienation, nationalism, nativism, nihilism, misinformation, disinformation, all of these things, all at once. There was resentment and rage, hucksters and hackers, bots and Nazis. (literal Nazis! As if they hadn’t been the unequivocal villains in every film for the last half century! For heaven’s sake, hadn’t these people ever even seen Indiana Jones?). It was all of these things, it was none of these things, it made no goddamned sense, that’s the point, and the only thing any of us knew for sure was this: on the ninth day of the eleventh month of the year of our lord two thousand and sixteen, our nation – and with it the world we’d known – had turned upside down.

Once, a lifetime ago it seems now, I interviewed a geologist. This was in the Before – before the world smashed to pieces, back when we could count on tomorrow unfolding more or less like it had today, which of course was more or less like yesterday and all the days before that. Find something interesting, the editor had told me. He’d said it vaguely, with a wave of his hand. Make geology relevant.

The geologist I’d interviewed was athletic and lean, pale as parchment. For two hours, she and I sat together in a windowless basement office in the science building of a mid-sized college campus. She explained that the Earth’s crust is always in motion, tectonic plates shifting endlessly, like jigsaw puzzle pieces shuffled around a table. The plates move so slowly that changes are largely imperceptible.

We think of an earthquake as a single moment in time, the geologist told me that day, when in fact it’s a centuries-long event. It happens bit by bit by bit, then all at once.”

But sometimes the jagged edges snag. The plates can’t get free, so they push against each other, like lovers who can neither separate nor get close enough. Pressure mounts, moment upon moment, decade upon decade. Eventually the planet cracks open, and nothing is ever the same again. We think of an earthquake as a single moment in time, the geologist told me that day, when in fact it’s a centuries-long event. It happens bit by bit by bit, then all at once.

She shared other things in that conversation – that the Americas and Asia will someday be a single landmass, one enormous supercontinent. That our oceans sometimes belch enormous boulders into open sky; recently, a stone two and half times the weight of the Statue of Liberty was hurled from the sea off the coast of Ireland. It sailed hundreds of feet through the air, then landed, to the bewilderment of locals, smack-dab in the middle of an open field.

But it was the earthquake part that I found myself thinking about in those days of what happened.

Bit by bit by bit, then all at once. That was how it felt: like pressure we hadn’t even noticed building had cracked wide open the ground we’d been standing on. Only after fissures had become chasms did we realize they’d been there all along. Sometimes the people who had been next to us just moments ago were now on the other side of a sharp divide, a canyon that no one could cross. It ripped people apart, this thing that happened. That’s what I’m saying. It tore entire lives asunder.

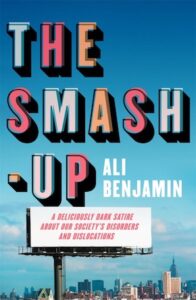

from The Smash-Up (riverrun, £18.99)

Ali Benjamin is the author of the young adult novel The Thing About Jellyfish, an international bestseller and a National Book Award finalist. The Next Great Paulie Fink was named a top children’s book of the year by Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly, the New York Public Library, and the Los Angeles Public Library. Her work has been published in more than twenty-five languages in more than thirty countries. Originally from the New York City area, she now lives in Massachusetts. The Smash-Up, a vibrant reimagining of Ethan Frome for the (post-)Trump and #MeToo era, is published by riverrun in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Ali Benjamin is the author of the young adult novel The Thing About Jellyfish, an international bestseller and a National Book Award finalist. The Next Great Paulie Fink was named a top children’s book of the year by Kirkus Reviews, Publishers Weekly, the New York Public Library, and the Los Angeles Public Library. Her work has been published in more than twenty-five languages in more than thirty countries. Originally from the New York City area, she now lives in Massachusetts. The Smash-Up, a vibrant reimagining of Ethan Frome for the (post-)Trump and #MeToo era, is published by riverrun in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

alibenjamin.com

@alibenjamin

@riverrunbooks

Author portrait © Sharona Jacobs