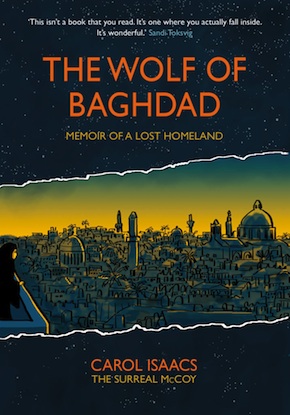

Homesick for another land

by Mark Reynolds

“Moving, powerful and beautifully drawn.” Steven Appleby

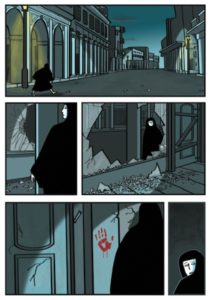

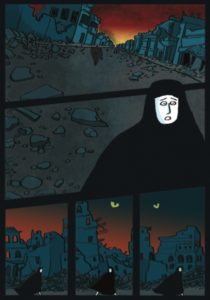

Musician and cartoonist Carol Isaacs’ graphic memoir The Wolf of Baghdad traces her family roots among Iraq’s departed Jewish community. Wordless chapters are bookmarked by the testimonies of family members who lived in and were exiled from Baghdad. Born and raised in London, fuelled by family anecdotes and customs, Carol grew up with a feeling of homesickness for a lost homeland. In the book, she is transported to a Baghdad of her imagination, accompanied by a lone wolf as mythical protector.

Having produced a three-page comic on her origins for a feminist anthology called The Strumpet, she began expanding the story into a longer form. And with musical ensemble 3yin (pronounced ayin, which means eye in Hebrew and Arabic), she developed an evocative soundtrack of traditional songs from the Judeo-Arabic tradition, which is played to accompany a ‘motion comic’ of the story. The piece is played live in concerts, and has been recorded for a DVD. The audiovisual part of the project was made possible through funding by Arts Council England and Dangoor Education, and an excerpt of the book-in-progess was longlisted for the 2018 Myriad First Graphic Novel Competition. Myriad Editions’ Corinne Pearlman tied up a book deal after an audiovisual performance at the Lakes International Comic Art Festival later that year.

The history of the Jewish population of Iraq goes back over 2,000 years, to the destruction of the first temple in Jerusalem by the Romans. “We don’t really have a family tree,” reflects Carol. “We have something of sorts that goes back to the late 1800s, but before that there’s really no knowledge of who we are, where we’re from. We’re just assuming we’ve always been in Iraq – tracing through culture and music and stories that are passed down. For example, my uncle recorded my late grandmother just before she passed away in the early 70s, telling these ancient folk tales of Iraq that were probably told to her by her grandmother. It’s an old Arabic that even Iraqis ask, ‘Where’s this from? This is wonderful.’ So things are passed down orally as well.”

“My father had all these connections still… Our house was like Little Baghdad. The Iraqi dialect was spoken, and there was a lot of laughter.”

Carol and her sister grew up in London, but always had a foot in two worlds. “My father was very much the city gent,” says Carol. “He had an office in the City and he went there till he was in his mid-80s. In the house, Arabic was spoken, the food was Iraqi, the culture was Iraqi, and outside I went to a very British school and I was English there – one of a very small minority of Jews in that school, and a minority among those Jews. I was probably the only one from the Middle East; all the other Jewish students were descended from Europe.

“My father had all these connections still. When he left Iraq he kept his business associates and friends. They would periodically come to England and he would be their conduit here to getting decent healthcare, and any other kind of needs they had that he could fulfil. They would come and visit us in our house in northwest London about once a month or so, and those occasions were wonderful. I remember them being like Little Baghdad. The Iraqi dialect was spoken, and there was a lot of laughter. I’m still in touch with the children of those families. We grew up together. Even though they came from such a long way away, we had a lot in common.”

“My father had all these connections still. When he left Iraq he kept his business associates and friends. They would periodically come to England and he would be their conduit here to getting decent healthcare, and any other kind of needs they had that he could fulfil. They would come and visit us in our house in northwest London about once a month or so, and those occasions were wonderful. I remember them being like Little Baghdad. The Iraqi dialect was spoken, and there was a lot of laughter. I’m still in touch with the children of those families. We grew up together. Even though they came from such a long way away, we had a lot in common.”

Back in the 1940s, a third of Baghdad’s population was Jewish. “This story is so little known, people don’t believe me,” says Carol. “I try to explain that there were Jews in Iraq, that it pre-dates the Muslims and Christians, we were a sizeable community, and it’s received with astonishment.”

That population began to crumble in the wake of the Farhud of June 1941, a violent pogrom that followed the defeat of Rashid Ali’s pro-Nazi government by the British – who subsequently withdrew from the city. Amid allegations that Baghdad’s Jews had aided the British, 179 Jews were killed and 911 Jewish homes were looted. “The end of the community was a perfect storm of many things,” says Carol. “It was a rise of a certain Arab nationalism at the time, there was a military coup that left a power vacuum, and the influence of the Nazis had been building since the 1930s – there was a heavy German presence in Iraq, sanctioned by Hitler – and so all those things just made it impossible to stay there anymore.”

A mass exodus came in 1950, when four-fifths of the remaining 150,000-strong population registered to leave for Israel. “Some of my parents’ family went to Israel, and ended up in those tents in the desert in the ma’abarot until they got rehoused. My father had worked for the British during the Second World War, and somehow got himself a British passport, so he left pretty soon after the war, came here and started bringing people out. He brought out his family – his younger brothers – saw one of them through medical school. And perhaps many others, I don’t know. He never talked about it. I never even knew what he did for a trade, he just said ‘import-export’.

A mass exodus came in 1950, when four-fifths of the remaining 150,000-strong population registered to leave for Israel. “Some of my parents’ family went to Israel, and ended up in those tents in the desert in the ma’abarot until they got rehoused. My father had worked for the British during the Second World War, and somehow got himself a British passport, so he left pretty soon after the war, came here and started bringing people out. He brought out his family – his younger brothers – saw one of them through medical school. And perhaps many others, I don’t know. He never talked about it. I never even knew what he did for a trade, he just said ‘import-export’.

“My mother was twenty-three years younger than him, he married very late in life, but the families knew each other. My mother left Iraq in the late 50s. She stopped in London on her way to America to join her sister, who was already settled there. My father had a small flat in St John’s Wood where all the émigrés would come and see him, he was the hub of activity, a fixer of things. So she stopped there and reconnected with my father and they fell in love and that was it, she never made it on the boat to America.”

During Carol’s untroubled London childhood, there were disturbing undercurrents coming out of the old country. After the Ba’ath party seized power in 1968, the movement came increasingly under the control of Saddam Hussein, who rose to become President in 1979 and plunged the country into war after war. “It was awful. In the 70s and 80s my father lost friends. I remember there was this one lovely elderly gentleman, a good friend of his, who just didn’t come any more. I was told later he was taken to one of Saddam’s torture jails and never left. So it was very sad to see what had become of that country. And again now, with all the protests of the young people in Tahrir Square, just protesting for a normal life and human rights, and seeing that squashed very brutally, is very sad. They just want to live their lives, have families, make a living like we all do.”

“I’ve always heard snippets of stories, anecdotes from my family about the life they lived.”

The book‘s moving testimonies from the family were gathered from a variety of sources. “Aside from the direct interviews I did, either face-to-face or on Skype, a lot of material was given to me by family members. My father died in 1992, and before he passed away I sat down with him with a tape recorder and got down some of his memoirs, the first thirty or so years of his life, before he got too sick to continue. One uncle wrote a little essay for his grandchildren about his life in Baghdad; and another had done a talk on the Jews of Iraq at the University of Nottingham, which he recorded.

“I’ve always heard snippets of stories, anecdotes from my family about the life they lived. They would tell these little anecdotes like how they used to go to the synagogue on a Saturday through the old Jewish Quarter, how my grandmother would keep house; she’d go to the market, she’d wear the abaya, she’d dress like all the other women so she’d blend in. We weren’t told really about the negative stuff, I kind of found that out for myself.”

“I’ve always heard snippets of stories, anecdotes from my family about the life they lived. They would tell these little anecdotes like how they used to go to the synagogue on a Saturday through the old Jewish Quarter, how my grandmother would keep house; she’d go to the market, she’d wear the abaya, she’d dress like all the other women so she’d blend in. We weren’t told really about the negative stuff, I kind of found that out for myself.”

In common with many cultures, the wolf is seen as a potent symbol of power and protection in Jewish and Arab tradition. “I inherited a lot of little amulets from my mother,” says Carol, “and among them was a wolf’s tooth. The hamsa, the eye within the hand, is a common theme in Jewish homes – and in non-Jewish homes as well, it’s the hand of Fatima. But I was a bit puzzled when my mum died ten years ago and I found the wolf’s tooth. Then I went to a museum in Israel, the Babylonian Heritage Center, and they have an exact replica in one of the cases. When I asked about it, I learned it would have been pinned to the crib of a child to protect against the Evil Eye. Digging further, I was travelling in Jordan two years ago on a hike with my partner, and we met some Bedouin there, and I asked one of them about the wolf myth and he said, ‘Yes, we have the same in our culture. We believe the wolf is a great hunter, we respect him, the women take parts of the wolf for use in folk medicine; we also take the tooth and put it on a string to wear round our neck to give us strength.’ And funnily enough, the translator who did the Arabic subtitles for the DVD told me that his grandparents lived in the marshlands of Iraq, and when they went out hunting one day they found a wolf cub and took it home, and raised it as a guard dog. They would take it hunting every time they went to the marshes, it would collect the geese and the ducks that they shot, and when it died they took its tooth out and also used it as an amulet. So it’s a pan-Iraq, Middle Eastern symbol or talisman. In the West we regard the wolf perhaps as something a bit malign, you know, The Big Bad Wolf, something to be afraid of, but not so much in the Middle East, it would seem.”

The music of the DVD and live performances combined with the motion comic offers a still more immersive experience. “It’s all either Judeo-Arabic music specifically from Iraq itself, some Iraqi folk songs, and some songs that were written by Jewish composers in Iraq in the 1930s,” explains Carol. “So it’s a mixture of secular and religious tunes. You’ve got the book experience but onscreen. The DVD is out in early March, and the next performance will be at the Jewish cultural centre JW3 on 5 March. There’ll be The Wolf in the first half, then a concert by the band of music from Judeo-Arabic sources.”

“There’s no house, there’s no cemetery. I wouldn’t have anything tangible to go back to, but it would be more about a connection, returning the story back to its roots.”

So have music and art have been equal passions throughout her life? “Not really,” she smiles. “I started off as a musician. I’ve been a professional musician all my life, and I became an accidental cartoonist, drawing cartoons, just single-panel gags, that ended up in The New Yorker, Private Eye and other places. I was on a long concert tour, I got bored and started doodling, and it morphed into this other career.”

Aside from exploring her Judeo-Arabic roots with 3yin, Carol has also been performing Eastern European music for the last decade with the London Klezmer Quartet: “That’s kind of how I came to Arabic music in a way, because a lot of the modes in the Eastern European Jewish tradition are the same as the ones in the Middle Eastern tradition, so when I first heard Klezmer I thought it sounded very oriental, and indeed there’s one mode – Hijaz maqam or Freygis –that is shared by Middle Eastern music and the Jewish tradition, so there’s a very pleasing crossover there too.”

Aside from exploring her Judeo-Arabic roots with 3yin, Carol has also been performing Eastern European music for the last decade with the London Klezmer Quartet: “That’s kind of how I came to Arabic music in a way, because a lot of the modes in the Eastern European Jewish tradition are the same as the ones in the Middle Eastern tradition, so when I first heard Klezmer I thought it sounded very oriental, and indeed there’s one mode – Hijaz maqam or Freygis –that is shared by Middle Eastern music and the Jewish tradition, so there’s a very pleasing crossover there too.”

Carol has been invited by the Iraqi Embassy to visit the country for the first time, but her feelings about going are equivocal. “I’ve got nothing to visit, really,” she tells me. “There’s no house, there’s no cemetery. Saddam Hussein bulldozed the major Jewish cemetery to build a highway in the 80s, so my grandparents’ grave will have gone, there’s nothing there. Some houses in the old Jewish Quarter are still standing, but in terrible disrepair. So I wouldn’t have anything tangible to go back to, but it would be more about a connection, returning the story back to its roots. And there is interest from some Iraqis, it would seem, about the history of their minorities. I’m not sure if now is the right time to go, again there’s a lot of upheaval and violence, but I do hope one day I will. My mother’s generation, her siblings, would say, what would we go back for? We were thrown out, we were ethnically cleansed from that country. The older ones who are no longer with us would say, ‘Well we enjoyed the good times, we got on with our neighbours and everything.’ A friend of my mother has gone back, and actually purchased a house in Erbil in Kurdistan. It’s more of a symbolic thing, but he travels quite a lot from here to Iraq. So I don’t know, time will tell on that one.”

Carol has thoroughly enjoyed her first foray in long-form graphic storytelling, and there’s a strong chance more will follow: “I’ve got a couple of ideas, we’ll see, nothing concrete as yet. This is a new world for me. I’ve never done anything of this length before, but it’s a really fascinating world and I’m captivated by it, I just can’t get enough of other people’s work. I’ve got a huge pile of books to read, these amazing stories, it’s just such a wonderful medium, to see how many different styles of comic-book artist there are, it’s incredible.”

Carol Isaacs is a musician and, as The Surreal McCoy, a well-known cartoonist published in the New Yorker, Spectator and The Sunday Times. She has worked as an accordionist and keyboard player with artists including Sinéad O’Connor and the Indigo Girls, and is co-founder of the London Klezmer Quartet and a member of the ensemble 3yin. The Wolf of Baghdad is published by Myriad Editions.

Carol Isaacs is a musician and, as The Surreal McCoy, a well-known cartoonist published in the New Yorker, Spectator and The Sunday Times. She has worked as an accordionist and keyboard player with artists including Sinéad O’Connor and the Indigo Girls, and is co-founder of the London Klezmer Quartet and a member of the ensemble 3yin. The Wolf of Baghdad is published by Myriad Editions.

Read more

thesurrealmccoy.com

@TSMCartoons

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista