Chibundu Onuzo: Sticking together

by Mark Reynolds

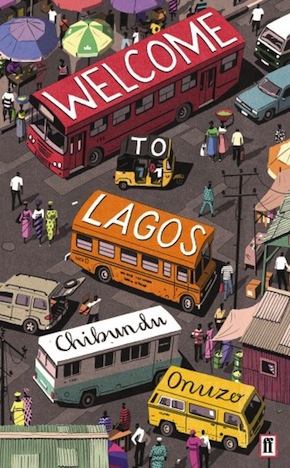

“A stunning portrayal of an extraordinary city.” goodreads.com

Chibundu Onuzo’s vibrant second novel Welcome to Lagos – following 2012’s acclaimed The Spider King’s Daughter – is the story of an unlikely band of runaways thrown together as they escape civil unrest in the Niger Delta to start a new life in Nigeria’s chaotic and sprawling megacity. Army officer Chike and loyal foot soldier Yemi abscond from the army and en route to Lagos pick up three other desperate souls in the shape of teenage militant Fineboy, feisty orphan girl Isoken and fleeing housewife Oma. Once in the city, they stumble upon a national scandal involving education minister Chief Remi Sandayo, who has embezzled $10 million intended for the country’s most dilapidated schools and is now himself on the run. On the chief’s trail is keen young journalist Ahmed Bakare, editor of the failing Nigerian Journal. It falls to each of the characters to make a life-changing choice between truth and morality, flight or fight, against a backdrop of corruption, brutality, desperate poverty, faith and daily kindnesses. I catch up with her at the Faber offices.

MR: How soon after completing The Spider King’s Daughter did you begin Welcome to Lagos, how long was the writing process, and how did it differ from the first time round?

CO: I began this straightaway. I actually began this novel even before I got a publisher, because there’s kind of downtime between when you send your agent something you’ve written and when they respond, so in those gaps I started writing what became Welcome to Lagos. I was reading Sea of Poppies by Amitav Ghosh. He had an ensemble cast with seven lead characters, and I thought, “Wow, this is so cool.” The Spider King’s Daughter had only two main characters, and I thought, “I want to write something like this,” but I didn’t know what. Then I had a dream about two soldiers – I’ve never had a piece of fiction sparked by a dream before, I don’t write down my dreams ever. But I thought it was an interesting dream, so I started with the two soldiers and then I thought, “What if another character joins them, and then another character, and another. Maybe this is my next novel.” What was different was that it took a lot longer than The Spider King’s Daughter. I started it when I was 18, pretty much straight after I had a draft of The Spider King’s Daughter, and we put the last full stop probably last January when I was 25, so it was seven years from start to finish.

And how did you fit the writing around your studies?

I studied History, and as anybody who studied a humanities degree will know, you don’t have a lot of contact hours. I think I had seven hours of lectures and seminars in a week. Obviously you still have to write essays and you have deadlines to meet, but it’s not like I was always in school, so I could really structure my time. I did a Masters, and I’m doing a PhD at the moment, so again I have that kind of space.

This story begins in the Niger Delta, where Chikwe and Yemi defy orders to shoot at civilians and become deserters. The conflicts in that region between international oil companies, the government and local tribes have lasted all through your lifetime. How can they be brought to an end?

I don’t know, is the short answer. Yes, they have lasted through my lifetime, but I haven’t been aware of it all my life. I grew up in Lagos, and sometimes Lagos can be very insular. It’s a very big city, with a population the size of many countries, so sometimes Lagos can just feel like its own thing. I became aware of the Niger Delta crisis maybe when I was a teenager. But how it can be solved, I don’t know. Businesses are not countries, they operate in their own interests, that’s how capitalism works, then it’s government that regulates business. Businesses will generally do what they can get away with – you see it in the banking industry here. The oil industry in Nigeria has not been properly regulated, so I think the burden is on the Nigerian government to stop taking backhanders and turning their heads away.

We now have things like Lagos Fashion Week, a very glitzy, New York type of event, but then the flipside is that the contrast between rich and poor is starker.”

How has Lagos expanded and changed since you were born there?

It’s definitely wealthier. We’ve had a big technology boom, we’ve had an internet boom to an extent, we’ve also had a financial boom – some of it riding on the back of oil prices, but Lagos has been very well placed to take advantage of that. So it’s definitely become wealthier and more glamorous in my lifetime. We now have things like Lagos Fashion Week, a very glitzy, New York type of event, but then the flipside is that the contrast between rich and poor is starker – or maybe I’m just glossing over my childhood and maybe the contrast has always been stark. I don’t know if I’m just being nostalgic.

The increased wealth also attracts economic migrants of course, from all over Africa.

Yes, the population size has grown in many ways. But the city is more sanitised, and crime has reduced. When I was growing up we were never robbed, thank God, but there was always that fear, and we knew people who’d experienced armed robberies. We never went out past 7 pm, but now my younger cousins stay out partying till 1 am. When I was growing up that was unheard of. Of course people would go out at night, but you were really taking a big risk, whereas now crime has reduced. It hasn’t disappeared, but it has reduced.

And have places like the floating slum of Makoko become more safe for those residents?

And have places like the floating slum of Makoko become more safe for those residents?

No, I wouldn’t say so. People with money feel a lot less scared about going out, but at the same time there’s always a threat when there are so many people living very tough lives. The government is always trying to destroy the homes of people in poor areas like Makoko. There’s this drive for ‘the new Lagos’, and while many parts of the city are getting wealthier and more glossy, there’s this other Lagos that doesn’t fit the dream. I reference it a little bit in the book, where I say Makoko is not on any official map. I don’t know if this is literally true, but it’s how it’s presented. The government calls it a ‘temporary’ settlement, though it’s been there for like a hundred years, and they keep trying to go in and demolish it because it and many other communities don’t fit with this progressive, wealthier Lagos. They always talk about the ‘urban masterplan’, but cities move around people. Human beings are more important than any neat plan you have in your office.

How does life in Lagos differ from life in the relatively small and much younger capital Abuja?

Lagos is better! There’s always a rivalry between Abuja and Lagos. People in Abuja say Lagos is too chaotic, it’s so messed up, so dirty, so disgusting. And people in Lagos say Abuja is so boring. Again, Abuja was built in the 1980s with the idea of creating a new city that doesn’t have any poor people – as opposed to actual poverty alleviation so you don’t have so much of the population under the poverty line that you need to shoo away. Abuja is a city built on displaced land, the original people who lived in Abuja, the Asokoro, were displaced. And that is still the drive. When we want to modernise, it seems we have to displace anything that doesn’t fit the plan.

Fineboy is a cunning and opportunistic but very likeable militant. How did you choose the name, and why did it fit this character so well?

When I was doing my research about the Niger Delta and names that were common there, and among militants, I just kept coming across all kinds of odd-sounding names. Fineboy is not the most outlandish. Sometimes the names can be a direct translation. It might be more normal-sounding in a Nigerian language, but when it’s translated into English it sounds funny. But I like Fineboy. My cousin says he’s her favourite character because he’s a ‘hustler’, which is a typical Lagos phrase. There are just some people you meet and you realise they’re people going make it in life, whatever the odds. You don’t trust them but they’re charming nonetheless.

Probably your most colourful character is the corrupt and charismatic education minister Chief Sandayo. How representative is he of Nigeria’s recent regimes?

I don’t know how representative he is, but are there people who have existed like him? Can I think of real-life examples? Yes. I watched a lot of interviews with Nigerian politicians before I wrote some of his scenes, and there’s often that kind of braggadocio, and the idea that nobody outside Nigeria has a right to hold them to account. At the same time we Nigerians feel a strange sense of national pride when we watch an interview where some dubious leader is giving as good as they get to a Western journalist. They make us proud for 15-minutes, but actually there’s a problem there.

Sandayo points out to the BBC journalist who takes up the investigation that in Britain it’s the descendants of the biggest thieves – slave traders and land-grabbers – that make the rules. And the name of the programme, West Presents, seems to suggest there’s often a one-sided view of news reporting internationally.

That was so not on purpose, I promise! I wanted names for the British characters to be really generic – you know, Richard Brown, David West – and I called the show West Presents, and only after I’d written the scene did I think maybe my subconscious was at work here. Once you see it, yes, there’s this idea that the West is presenting Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Thailand, wherever, but I think the subjective nature of news is fine. The problem is that, here anyway, you never get the Nigeria Presents version, you never get Thailand Presents. I’m not against subjectivity, it’s just a fact of life. Everybody has their perspective on a set of events, it’s just that some perspectives are never represented on the so-called worldwide stage – which is why we’re so happy when these Nigerian politicians get to show their defiance.

There’s a nice twist in that Sandayo, despite his brazen theft, identifies with Christ as a benefactor and martyr – and thanks to the BBC’s coverage, this is how he will be most broadly remembered.

I think the point I was trying to make is that nobody serious stands up to close scrutiny, no matter who it is. I was reading a book called Young Mandela about how Mandela wasn’t so nice in his early life, and you can read these kinds of works on Gandhi, Winston Churchill, any national hero. If you look too closely, you always see things you don’t like, and Sandayo is no different.

Chikwe’s nightly Bible readings help bond the group together. They seem particularly drawn to the more supernatural stories in the Bible. How does Christianity in Nigeria differ from elsewhere? Does it plug into a more ancient spirituality?

We had Bible study every morning in my house when we were growing up, when the whole family would come together, so maybe that’s part of why that’s in the book. As to Nigeria’s connections to ancient spirituality, I don’t think a belief in the supernatural parts of the Bible is tied just to Nigeria. I’ve been to church in Brazil, and the feel of the Pentecostal worship was similar. I’ve been to Charismatic churches here, both Anglican and non-denominational, and again I think people are drawn to different parts of the Bible.

But does older folklore also somehow disseminate into religious belief in Nigeria?

To some extent, yes. You have some churches that fuse African traditional belief and Christian belief. Those churches are quite old, actually, some a century old. It was partly to do with cultural nationalism, they left the Anglican church to form these African churches because they felt their culture was being denigrated in the more straightforward Anglican churches. In my church in Nigeria, for example, we sing in Nigerian languages, we use Nigerian instruments, while the sermon is often in English. But there’s also a belief in the supernatural in expressions of Christianity in other countries. It’s good that to a large extent the message can remain the same, though the expression is different. In my father’s generation, some churches wouldn’t allow drumming, or wouldn’t allow expressions of culture, whereas I haven’t had that experience. People often ask my father why we don’t have Christian names, and he says, “No, they don’t have English names. It’s not that they don’t have Christian names.” It’s important to hold on to that dual identity.

How many small independent newspapers like Ahmed’s Nigerian Journal exist around the country – and how long do they typically last?

To be honest, I don’t know. But Ahmed’s journal is roughly based on one that folded, and while it lasted it burned very brightly and even now people talk about it nostalgically. It started in the noughties, I think. Ahmed’s journal is not that newspaper, but it’s inspired by it in a loose kind of way. It had good production values and was very anti-corruption, but sadly the figures didn’t make sense. There was a lot of political opposition to it as well, because obviously they were doing all these exposés.

I think it’s natural for many people who feel strongly about Nigeria and wish it could change, that at some point it will cross your mind to go into public office.”

Ahmed’s father cautions, “You think you can write anything you like in Nigeria?” But there is a relatively free press in Nigeria still.

Oh yes, there is. Government patronage is very important, and bosses of private companies can say don’t advertise in that newspaper because they’ve done x, y, z. But the press is free, the press can say whatever it wants, and even if the print papers can be more closely aligned to the government, on the internet there’s one particular newspaper called Sahara Reporters, based in America, that publishes anything and everything. But then how free are you when you are poor? Journalists are often not paid very well, so someone can just bribe you to suppress or change a story. So it’s not that you print something and you’ll be thrown in jail, but the financial consequences of printing something can be high.

You said in interviews around the time of the last book that you might run for public office at some point. Are you still considering it?

In theory. I used to say I want to be an elected official by 30, so I have five years. I think it’s natural for many people who feel strongly about Nigeria and wish it could change, that at some point it will cross your mind to go into public office. But I don’t know.

Looking further ahead, do you think there could be a female president of Nigeria in your lifetime?

Definitely. Without a doubt. Equality is not parity, so there are not 50% women and 50% men in parliament, but at the same time women have held very powerful positions. Our current Minister of Finance is a woman, our last Minister for Petroleum was a woman. There’s never been a problem with women having the top jobs, but if you drill down there’s also a class issue, these are always people from a privileged elite. If you’re from an elite family and go to school abroad you’re in that circle. The question is, will women be more represented and more empowered lower down? But a female president I definitely believe is possible in my lifetime.

Nigeria is divided in terms of rich and poor, by region and ethnicity, religion and culture, but as you show there is solidarity among mixed communities at ground level. How can Nigerian society be unified on a national scale? Or might separation back into microstates be more stable and viable?

Are you talking about Britain or Nigeria? What you’re describing could be anywhere in the world right now! I don’t think we should separate. There’s a resurgent pro-Biafra sentiment, and I think economic hardship exacerbates separatist feelings, because manipulative people will always say everything would be fine if only we had our own nation. I don’t think it’s true. I don’t think the leaders of any of the separatist movements have the interests of the people at heart. It’s an old cliché, but we are better together: our numbers, the size of our market, as a country if we can make things work we can be a major player. We’re already a major player in Africa, but we can be a major world player.

Wiliam Heinemann first edition, 1958

Back to books, who were your first literary heroes?

I read lots of classics when I was growing up, British classics like Charles Dickens, the Brontës, Jane Austen, and things like Lorna Doone – some of the random ones that are not widely read anymore as well as the more famous ones, because these were the books my mother read when she was growing up. She had ‘a very good colonial education’, so those are the books she bought for us. I read a little bit of African fiction, but not so much until I moved here. I read Things Fall Apart for the first time here, and I think that was my doorway into Nigerian fiction, so I started at the beginning. And maybe I’d read Purple Hibiscus when I was in Nigeria, but I was too young to understand it. I reread it quite recently as an adult and I appreciate it more. But Things Fall Apart I remember was like the first book that struck me, then I read all Achibe’s novels, moved on to Wole Soyinka, read some Nadine Gordimer, Coetzee, others from around the continent.

What are you currently reading?

Actually right, right now I’m rereading Gone With the Wind. There was a deal on Kindle so I downloaded it – and I was so horrified! After about the first 50 pages I was like, how was this allowed to be written, this kind of merry slavery? There’s literally a line where she says the slaves were never beaten. What do you mean, the slaves were never beaten? So I downloaded Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, which despite all the fantastical elements is still a more realistic portrayal of slavery. So I read that and now I’ve gone back to Gone With the Wind and now I can manage all those lies, and focus on the relationship between Scarlett and Rhett, which is very nicely done.

How far are you into your next project?

I’m about five chapters in. I’m not as far along as I was with this one by the time The Spider King’s Daughter was coming out, because I guess I’ve been doing more PhD stuff – which I really do want to get done next year. But I’ve started, and it’s always good to have another one underway.

Finally, jumping on a small detail, tell me about the tales of Ijapa the tortoise that Ahmed’s father read to him as a boy.

In Yoruba folklore – and also in Igbo and across West Africa – he’s this wily character, like Brer Rabbit or Anansi, who’s always trying to trick all the animals. Sometimes he gets away with it and sometimes he doesn’t, but there’s always a moral at the end of the story. There’s one where he borrows feathers to go to heaven for a party, and when he gets there he says, “My name is ‘All of You.’” So every time they bring food and say, “This is for all of you,” he stands up and claims it. Then when the party’s over the birds take their feathers back so he can’t get home, and the moral of the story is all about cooperation and sharing; it will come back to bite you if you don’t share.

Chibundu Onuzo was born in Lagos in 1991 and moved to Britain at the age of 14. At 19, her first novel The Spider King’s Daughter was picked up by Faber based on an early draft. Published in 2012 to great acclaim, it won a Betty Trask Award and was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Prize and the Dylan Thomas Prize. Welcome to Lagos is out now from Faber. Read more.

Chibundu Onuzo was born in Lagos in 1991 and moved to Britain at the age of 14. At 19, her first novel The Spider King’s Daughter was picked up by Faber based on an early draft. Published in 2012 to great acclaim, it won a Betty Trask Award and was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Prize and the Dylan Thomas Prize. Welcome to Lagos is out now from Faber. Read more.

@ChibunduOnuzo

Author portrait © Blayke Images

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista