Crying wolf

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A powerful novel of extraordinary momentum and contemporaneity… both gripping and unsettling.” Der Spiegel

Millennial moments are full of auguries and momentum, real promise or sly illusions. They trick us into a sense of tabula rasa, into an exalted feeling of weightlessness from the past and its responsibilities, its phantoms and nightmares, but also from the effort to match and sustain its legacy of greatness and wisdom. It is a suspension of gravity and disbelief that we choose to see as an empowerment for limitless flights – of stunning vision or reckless audacity. Fools that we are, we choose to credit milestones of history, centennial crossings, clean breaks or personal Rubicons with an automatic power of total change, rebirth and rewriting. We somehow relish the sense of doom, decline and decay in fins de siècle, the razing-to-the-ground scale of catastrophe that they imply, revelling at the prospect of erecting new cloud-cuckoo-lands, or the opportunity to dismiss wrongs and errors, as though beginning ex nihilo also guaranteed clarity, maturity and infallibility – as though it provided, above all, unconditional, and especially effortless, purification from all sins of human doing and undoing.

One Clear Ice-Cold January Morning at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century is a novel poised at precisely such an almighty, precarious point in time. It gazes wondrously at the new century whose advent hails a new era of humanity – where as yet inconceivable technological progress, the super-humanity of AI, and the breakdown of all socio-structural constraints, will deliver a society so perfect, so superlatively advanced, as to almost make human intelligence, identity or even existence, superfluous and redundant. The pervading foundational myths of this new time beyond human limitations would have us look at androids (gynoids seem to have lost, yet again, the lexical battle of the sexes) capable of the emotions and experiences that we, their creators, seem to be disqualifying ourselves from; they would have us gawp at human computers (and not brains) emulating nature – or denaturing its every element, and expectantly look forward to an eternity of impermanence that marches on in as much steely darkness as it blazes forth in blinding light.

“We see in merry-go-round fashion consecutive glimpses of nine fractured lives which, as the revolutions of the fairground contraption get faster, fuse into one devastating scene of total visual and experiential collapse.”

Playing with his title’s connotations and echoes of such a new dawn, and with this sociohistorical backdrop in mind, Roland Schimmelpfennig shockingly reverses readerly expectations and conjures up for us a superbly dark comedy of manners, capturing the gestures of a humanity under threat of extinction, and sketching for us its almost dying motions. Over several clear (or foggy) ice-cold January mornings, he directs for us this human comedy on what feels like a revolving stage: we see in merry-go-round fashion consecutive glimpses of nine fractured lives which, as the revolutions of the fairground contraption get faster, fuse into one devastating scene of total visual and experiential collapse – but also perhaps of flickering hope. A wolf, a wildly anachronistic creature, stranded in this new space and time as though accidentally ejected from very different foundation myths and existential narratives, sets into motion a series of beginnings/turning points in each of these nine lives. Each story, like a spring-trap ready to snap at the slightest trigger, has an irreversible direction in its rhythm and motion; poignantly prosaic, uncompromising in its authorial austerity and its narrative frugality, each strand will bind a character’s destiny or cut his life thread. Each story will catch humanity at its most mundane or at its most exposed and desperate, also at its most brutal and wolf-like.

A hunter will die in the snow having gazed at the wolf; a boy and a girl will run away from familial darkness into the archetypal darkness of a wood, then into the murkiness of urban mores and emptiness; the girl’s separated parents will face monsters and demons in an unequal combat; the boy’s father will seek redemption, from both heaven and hell; a young Polish migrant will capture the wolf in a photograph and by this act, after what seems like a descent into the underworld, will claim back his place in his life – and the Polish girl of his childhood; a Pozzo and Lucky couple will follow a less exalted path into a reality of lunacy and abjection; a second-generation German woman of Turkish descent will seek a place of real naturalisation through fake stories leading out of her ethnic insularity; an elderly couple will live in madness and a state of occupation in an apartment block they refuse to surrender to a property developer; the daughter of free-living art collectors will burn the records of her mother’s past. A silent, all-present non-character is East Germany – a spectre of history that is yet to be dealt with.

The wolf has the stealth of an omen, the menace of dire doom; yet in the end, he causes no death, no incident, not even an inadvertent stampede.”

The wolf provides the connective thread through all these lives, or performs the vital incision that will release the puss from the festering wound that is each of these lives; he looms through each narrative, each scene, each stage of being or non-being as an apparition, especially of fear: real fear, hysteria, neurosis, existential angst, xenophobia, panic. Fear, essentially, of our own humanity. As he defines each space where he is sighted, if only for a fleeting second, he reveals (or exposes) outer deserts and inner cages. The wolf is like a savage, terrible, yet infinitely spellbinding unicorn. Elusive, mysterious, intangible, yet also solidly there, he is part of the disjointed myth the characters of the story have learned to call reality. As the wolf wanders into Germany from Poland, desperate for food and survival, he becomes a cutting metaphor for our own state of civilisation or barbarity. His decline from hunter to scavenger becomes inextricably linked to each human fate, acquiring a biting universality and irony: in acting as a catalyst for the actions and reactions shaping each human destiny, the old adage perhaps becomes lupus homini humanus. It will take a wolf for us to seek our lost humanity.

The wolf has the stealth of an omen, the menace of dire doom; yet in the end, he causes no death, no incident, not even an inadvertent stampede. Having electrified innumerable lives, gained notoriety, real or constructed, in the media, and leaving behind him only a few carcasses of sheep or chickens, the wolf disappears, leaving behind an even more acute sense of vacuity and absence. Like the barbarians that never arrive in the poem by Constantine Cavafy, the wolf had been “a kind of solution” for a society in climactic crisis.

One Clear Ice-Cold January Morning at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century reads like a quick succession of interlaced, portentous one-act plays (Schimmelpfennig is, after all, a master dramaturge), and this combined quality of stage economy and theatricality accentuates what is essentially a particularly unflinching, penetrating gaze into the state of our society. Jamie Bulloch’s translation is perfectly pitched between sharpness of diction and fluidity, capturing the ‘endless bowing’ feel of the German original with compelling English mellowness and crispness. This is a novel that is unashamedly accomplished without ever compromising its meaning for the sake of its form.

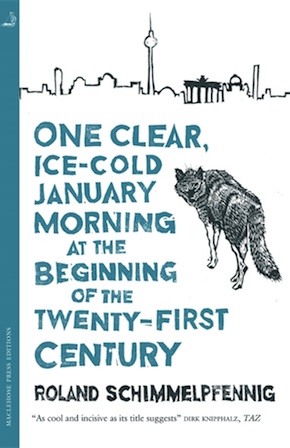

Roland Schimmelpfennig, born in 1967 and based in Berlin, is Germany’s most celebrated contemporary playwright. He began his career as a journalist before studying to be a theatre director, and his plays have been performed in over forty countries. One Clear, Ice-Cold January Morning at the Beginning of the 21st Century, his first novel, was shortlisted for the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2016. Jamie Bulloch’s translation is published in paperback and eBook by MacLehose Press.

Roland Schimmelpfennig, born in 1967 and based in Berlin, is Germany’s most celebrated contemporary playwright. He began his career as a journalist before studying to be a theatre director, and his plays have been performed in over forty countries. One Clear, Ice-Cold January Morning at the Beginning of the 21st Century, his first novel, was shortlisted for the Leipzig Book Fair Prize in 2016. Jamie Bulloch’s translation is published in paperback and eBook by MacLehose Press.

Read more

Author portrait © Heike Steinweg

Jamie Bulloch is a historian and has worked as a professional translator from German since 2001. His previous translations include Look Who’s Back by Timur Vermes, The Empress and the Cake by Linda Stift, Kingdom of Twilight by Stephen Uhly and The Last Summer by Ricarda Huch.

@jamiebulloch

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.