Elena Ferrante’s shadow lives

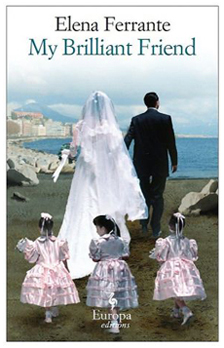

by Mika Provata-CarloneElena Ferrante writes beautifully. She writes honestly, powerfully, with directness and unflinching immediacy. In My Brilliant Friend and The Story of a New Name, the first two of her Neapolitan novels, she writes about a world which no longer belongs to what we might call our ‘reality’; the world of the fifties and sixties, of old darkness and long-awaited light, of the ambivalent seductiveness of La Dolce Vita – and everything that lies behind it. There is the squalor and the open wounds, the terror and the menace of film noir and Italian realism; there is a new era of prosperity, an intangible beau monde full of promise and potential ugliness; there is, very crucially, memory erased but still screaming. These first two volumes are about a world still under the clouds of World War II, fascism, black markets and black shirts, and about people yearning for the shadow of a dream, for a “getting out of the before” (My Brilliant Friend).

This is raw humanity, naked and innocent like a baby, or stripped-down naked, terrified and cold. It is also animal men and women, rising brutally out of emptiness, brandishing before time and eternity the threat and the reality of violence, ambition and greed. These are novels about the weak and the strong, about good and evil, matter and spirit, the flesh and the soul, hope and despair. They are also the narratives, fully, intimately told, of particular men and women, the story of a specific moment in time, the tale of a nation.

In the third volume of the series, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, Ferrante moves to a time of suspension, perhaps of erasure, a time beyond remembrance and before an actively lived present – hers and ours, promised and dreamt of but not yet realised. Ferrante calls this ‘Middle Time’ and it is a time of overmastering realism, itself still inescapably dominated by the past of the first two novels. At its centre are Paris ’68 and the intellectual and political explosions that were born from it, thought and idealism versus ideology, Left- and Right-wing terrorism, the evolution and devolution of society, technological development and cultural progress, aggression, regression. ‘Middle Time’ is a time of dreaming and of reality, historically shapeless and hazy, reactionary, yet once again gripping the characters and the reader like a vice. Ferrante has the courage, the shrewdness, to analyse and feel at the same time. She has critical empathy with history and its participants, with their human rights and needs, their yearning for a vision and their blindness. She does not accuse, she shows and reveals – how the dream of revolution became a nightmare of terror, how the necessity for order and reconstruction became greed and fascist revival. There are fascists right and left, Ferrante tells us, and in the middle lies humanity crushed, trying to breathe, think, live, hope: simply be, instead of constantly and uncertainly becoming. “And she suddenly asked me, as if she really wanted an opinion: do you think I exist? Look at me, in your view do I exist?” says the heavily made-up, heavingly voluptuous fiancée of Michele Solara, the sharp, cold-blooded and ruthlessly violent local Monarchist-Fascist Camorrist boss in Those Who Leave.

If you can see, read and spell out your destination, then destiny is yours, the third novel seems to say through each of its characters.”

Ferrante gently guides our vision to the individual lives trapped in what a character calls “the experience of filthiness”. She finds with infinite wisdom and subtlety, with perfect astuteness, Marie Cardinal’s “the words to say it” – ‘it’ being not one thing but many concurrent staggering challenges: the guilt of the one who has left and has been saved (question mark) towards the one who morbidly decides to stay behind and be damned (another tremendous question mark); the possibility of continuity in life, in memory, in narrative, in self-identity, the question of such continuity, the need, but also the terror of it; the yearning and the anxiety for wholeness – a repeated motif in the life of the protagonist Elena Greco, in her story of Lila, what the novels call “a restful tidiness” versus “dissolving boundaries”; most importantly, ‘it’ is destiny and destinations: “what word has she put in front of him: destination. Certainly a word that Gennaro [Lila’s five-year old son] had never heard”. And Lila continues: “if Nino [the father, the one who has left] had had him… that child would have had a completely different destiny.”

If you can see, read and spell out your destination, then you have a destiny, destiny is yours, the third novel seems to say through each of its characters, and especially through Elena, who studies and writes, discovers and enjoys motherhood, falls mute, discovers womanhood and writes again. She first writes a novel that must be discarded. It is a process of emptying out the past in order to clear out a space for the future and that future must question past and present, men as well as women, their past apart, their future together. Ideologies and traditionalist structures have failed so far: “How many people: mostly males, handsome, ugly, well dressed, scruffy, violent, frightened, amused,” says Elena of her audience at a presentation of her first, highly successful book. “We found ourselves, we… women, in the situation of drowsy heifers waiting for their bulls to complete the testing of their powers.” This third novel stretches our mind, our perception, every social observation, theory and historical assessment to its limits and towards its true purpose as concerns the ‘exteriority’ of men when it comes to women, the presumed incompatibility, the natural estrangement, all the Mars and Venus clichés and stereotypes. Elena marries Pietro, a perfectly gentle, brilliantly cerebral intellectual. The marriage fails for lack of understanding, mutuality, intellectual dignity and commonality. Elena yearns for a different male-female balance, a “two distincts, division none” kind of proposition, and she discovers feminism. A very shrewd and self-aware feminism, a person’s feminism and not the feminism of a robotic ideologist. She analyses feminism beyond the theory, seeking a possible human, female reality, overturning gently, judiciously, determinedly, “the coarse language of the environment we came from [which] was useful for self-defence, but, precisely because it was a language of violence, it hindered, rather than encouraging, intimate confidences.”

If you can see, read and spell out your destination, then you have a destiny, destiny is yours, the third novel seems to say through each of its characters, and especially through Elena, who studies and writes, discovers and enjoys motherhood, falls mute, discovers womanhood and writes again. She first writes a novel that must be discarded. It is a process of emptying out the past in order to clear out a space for the future and that future must question past and present, men as well as women, their past apart, their future together. Ideologies and traditionalist structures have failed so far: “How many people: mostly males, handsome, ugly, well dressed, scruffy, violent, frightened, amused,” says Elena of her audience at a presentation of her first, highly successful book. “We found ourselves, we… women, in the situation of drowsy heifers waiting for their bulls to complete the testing of their powers.” This third novel stretches our mind, our perception, every social observation, theory and historical assessment to its limits and towards its true purpose as concerns the ‘exteriority’ of men when it comes to women, the presumed incompatibility, the natural estrangement, all the Mars and Venus clichés and stereotypes. Elena marries Pietro, a perfectly gentle, brilliantly cerebral intellectual. The marriage fails for lack of understanding, mutuality, intellectual dignity and commonality. Elena yearns for a different male-female balance, a “two distincts, division none” kind of proposition, and she discovers feminism. A very shrewd and self-aware feminism, a person’s feminism and not the feminism of a robotic ideologist. She analyses feminism beyond the theory, seeking a possible human, female reality, overturning gently, judiciously, determinedly, “the coarse language of the environment we came from [which] was useful for self-defence, but, precisely because it was a language of violence, it hindered, rather than encouraging, intimate confidences.”

All three books seek precisely that: intimate confidences, a permanent lull in the violence, “the capacity to put together the fragments of things in [one’s] own way”; they long desperately, spasmodically, lyrically, for more permanent rather than permanently “provisional… fixed points”. They ultimately yearn to be able to hope that “the new living flesh [would stop] repeating the old in a game, [that we would no longer be] a chain of shadows who had always been on the stage with the same burden of love, hatred, desire and violence.”

Ferrante has said in one of her rare interviews that “in literary fiction you have to be sincere to the point where it is unbearable” and she confronts her readers fearlessly with all that is unbearable in the everyday life of her young people growing older and eventually old. Her Naples has thugs and cowards, dirty roads, filthy flats, cockroaches and pervading stenches. It has poverty, beaten men and subjected women. It has shopkeepers, shoemakers, greater and lesser public sector employees, self-important minor poets or mortadella tycoons, her Milan and Florence are infested with revolutionaries who lose their revolution and find utter blackness, a newly rich middle-class unsatisfied with its illusions and delusions, it is populated with professors who teach but will not be taught, publishers who are “very clever to guess that [one is] clever”. Her Italy is haunted by gaudy and ruthless Camorra bosses, their girlfriends and their underlings, by “Archangels without annunciations” in the form of passionate yet fleshless idealists. It has fragile people living in a meaningless world of their own, brilliant beautiful people trapped in a vileness for which they are responsible but also not altogether so. This Naples/Florence/Milan, this Italy and this world, has passions, murders, rites of passage, births and funerals, marriages and lustful cravings, obscenity, vulgarity, toughness. It has friendships, betrayals, joys and discoveries, unspeakable beauty and unutterable misery. It has people whose lives are lived and told breathlessly. These three novels absorb the threads and storylines of many books; echo the voices and teachings of many wise teachers or foolish men. They are inhabited by students of both literature and life, who try, fail again, fail better, “in order to be able to say… yes, I understand, I know.”

Above all these novels are gripping. They do not let you go, and once you begin reading them, you do not want to let go of them either. There are frequent moments when the pain of reading is excruciating, when the horror of understanding leaves you speechless. And yet to stop reading would be a betrayal. Of oneself and of everything that constitutes life. These stories are truly “the lie that always speaks the truth”, as Cocteau would have it, and the pain and the horror of the reader are also the pain and the horror of the writer, who acts as a vulnerable yet unwavering witness to our own madness, to our insane ability for destruction and self-devastation.

My Brilliant Friend and The Story of a New Name are full of this unwavering vulnerability; they are true tragedies inviting compassion, offering catharsis. There is the chorus of what a teacher calls “the plebeians”, and Dante had already called the ignavi, gossiping, chattering, spreading rumours, spite and some truths. From within this same mass of mankind, emerges Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, especially Elena Greco, who insists on dreaming, living, hoping, remembering – and writing. It is through her that we learn, that we see, that we know and feel. It is she who makes Ferrante’s stories different from the vulgar voyeurism, the exhibitionism and sentimentalism, the indulgent vicious violence of so much of contemporary prose. Elena is the redeeming difference, the gentle assertion that there may be full-blooded life waiting to happen for all the abysmal bleakness and recorded unnameable horror of so many of the individual lives. And this is perhaps the most powerful, entrancing charm of these novels: their determined faith that there is something beyond the direness. Elena is God’s ironic answer to man’s despondency.

My Brilliant Friend and The Story of a New Name are full of this unwavering vulnerability; they are true tragedies inviting compassion, offering catharsis. There is the chorus of what a teacher calls “the plebeians”, and Dante had already called the ignavi, gossiping, chattering, spreading rumours, spite and some truths. From within this same mass of mankind, emerges Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, especially Elena Greco, who insists on dreaming, living, hoping, remembering – and writing. It is through her that we learn, that we see, that we know and feel. It is she who makes Ferrante’s stories different from the vulgar voyeurism, the exhibitionism and sentimentalism, the indulgent vicious violence of so much of contemporary prose. Elena is the redeeming difference, the gentle assertion that there may be full-blooded life waiting to happen for all the abysmal bleakness and recorded unnameable horror of so many of the individual lives. And this is perhaps the most powerful, entrancing charm of these novels: their determined faith that there is something beyond the direness. Elena is God’s ironic answer to man’s despondency.

Ferrante shows throughout a very fine talent for subtle humour and mischievous satire. We read of Elena giving a volume of Beckett to another character: “I took the volume of Beckett, the one I used to kill the mosquitoes, and gave it to her. It seemed the most accessible text I had.” We are also told of the reaction of Elena’s father at the publication of Elena’s first novel: “My father said: ‘It’s my surname’, but he spoke without satisfaction, as if suddenly instead of being proud of me, he had discovered that I had stolen money from his pocket.” Yet Ferrante is never sarcastic. She is shrewd, perceptive, demanding of her characters and her readers. She expects truth and courage for life. Elena has a shadow in the novel – or she thinks that she is herself the shadow of this character, Lila, the effortlessly, exceptionally brilliant, stunningly beautiful friend of her childhood. Their relationship is one of inseparable opposites, as is so much in these books, in our lives. The struggle to love and not be possessed, to give and take, yet neither devour nor be subsumed, to grow up without growing away from, the sense of a past, a present and a future, are central concerns of the novels, dealt with meticulously, with absolute honesty, and with serious determination. There is continuous chilling suspense or burning excitement, constant undermining of great expectations, there are unfulfilled promises, reversals, and even veritable, terrible revolutions. There are passages which in the hands of many other writers would have loomed as merely trite and risqué, yet here they reveal Ferrante’s courage to take the risk of speaking, feeling, resurrecting humanity in a merely vulgar dehumanised world.

These are books to cherish, to share, to discuss vividly and vitally; they are especially books to remember, books that teach us how to remember and even how to forget. Ann Goldstein’s translation is truly gifted. It has all the lyricism which makes transcendence possible, it is blessed with beautifully balanced echoes of the Italian cadences and idiosyncrasies. One can only look eagerly forward to reading these books again, and to reading more Neapolitan novels.

Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend (2012), The Story of a New Name (2013) and Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014), translated by Ann Goldstein, are published by Europa Editions. A fourth book in the series will be published in 2015. Read more.

elenaferrante.com

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.