Ellen Hawley: Hard-earned love

by Farhana GaniAs any art director, editor or marketer would insist, a book should always be judged by its cover. What made Other People Manage so pickupable for me, was the immediate association with books by Anne Tyler, Carol Shields, Alice Munro, Suzanne Berne… you get the picture. Physically, and thematically, this book resembles those other rather wonderful stories of ordinary middle-American people making the best of their space, time and place as small dramas ignite their everyday lives.

Ellen Hawley’s first novel to be published in the UK is a book about joy, sorrow and deep loneliness. You’re plunged into this from the very first line. Marge, a bus driver, and Peg, a psychotherapist, have been together for over two decades, and after Peg dies from cancer, Marge finds herself bereft and alone.

They first got together in the 1970s after meeting at the Women’s Coffee House in a small Minnesota town. It was a place where gay women could hang out and dance together unhindered. In spite of, or perhaps because of their very different personalities (Marge laconic; Peg rarely lost for words), they were drawn to each other. However, Peg was being pursued by Megan, a three-night stand who became obsessed and started stalking her, until a devastating event cemented the foundations of Peg’s new life with Marge.

Over the course of the novel their ups and downs unfold. There is humour, sweetness, consideration and drama. Peg’s family is large – two younger sisters, down-to-earth Jude and flighty Deena and a sharp-tongued mother, Rose. Marge is warmly welcomed into their relatively untroubled world. Things take an unconventional turn when Deena first becomes pregnant at 17, and even though the family all step up to help raise her children, Deena is an unreliable mother, disappearing for long stretches. Marge and Peg become even more involved in the children’s lives after Jude unofficially adopts them.

After Peg dies, Marge finds herself newly detached from the family, an outsider, and in this new phase of life she must accept a new way of managing.

It’s not a plot-heavy story but, like the brief, sure strokes of Annie Proulx’s ‘Brokeback Mountain’, its impact is like a rupture. I was left with a deeply unsettling and authentic sense of bittersweet melancholy – a fleeting glimpse into the loneliness that comes from losing a life partner too soon.

Ellen sent Other People Manage to Swift Press unsolicited. This is one of those rare and incredible stories in book publishing – a hidden literary beauty, brilliantly told, picked up by an astute publisher who immediately recognised its quality.

Click on images below to enlarge and view in slideshow

Farhana: Your UK debut was plucked from the proverbial slush pile. Can you tell us more?

Ellen: My agent had retired and I was in the dispiriting process of sending queries to some endless number of agents. One had just turned it down after reading the chunk she’d requested, which cut off when the characters’ lives were at a low point. “It runs out of energy,” she wrote. I emailed to ask if she’d be willing to read a bit further, since it picked up soon after that and the low point was necessary. Silence.

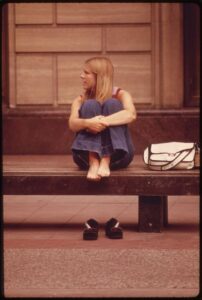

Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

Not long before that, I’d sent Swift Press a novel that had been published in the US – a political satire about fake news, which had suffered from lousy timing, since it came out during the hope-and-change optimism of Obama’s first run for the presidency. I was trying to revive it with a British edition, since it’s more relevant now than ever. I had its US publisher’s OK for that, but it was unagented so I was limited to small presses.

Swift was new and I gambled that they’d actually read their slush pile. Or at least glance at it from time to time. The publisher, Mark Richards, emailed to say it had come out too long ago to be commercially viable, but did I have anything else? Well, yes, I did, but by then I’d heard from that one damn agent and begun to wonder if she was right, so I reread Other People Manage to see if I should commit myself to a massive rewrite. No, I decided, the energy changed, but it needed to. I sent it off.

Within what I remember as days, although it might’ve been a little longer, Mark wrote back saying, simply, “I love it.” I’d published three books by then without an acceptance letter ever saying that. If there’s a moral to the story, it’s that experts will disagree about what works and what doesn’t. As will readers.

Tell us about your writing history.

I’ve published three novels in the US: Trip Sheets, Open Line and The Divorce Diet. Other People Manage is my first in the UK and the first one that a publisher has committed itself to so heavily.

How would you pitch your latest book in up to 25 words?

Other People Manage is about the hard-earned, everyday love between two women. It’s about family and grief and pain – and the love that gets us through. (I cheated. That’s 26.)

Inevitably, I draw from real people – this person’s energy or their impact when they enter a room; the way that person is in the world, or at least how they seem to me.”

Was there a particular event, person or insight that inspired this story, and did you have any concern it could be viewed as autobiographical?

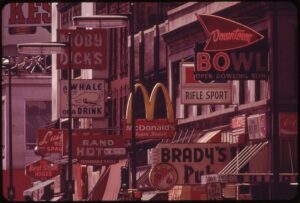

Hennepin Avenue, downtown Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

Maybe this is naive, but the events are far enough from my own life that I never thought about anyone assuming it’s autobiographical. Still, to some extent our characters and stories can only come from our own understanding of people, which is to say from the lives we’ve lived. My novels have mined the jobs I’ve held and the jobs that friends have held. I’ve set my stories in communities I know and understand. I can see where that would give the appearance of autobiography, but to date I haven’t written anything based on my own life.

With one exception, I’ve been careful not to base any of my characters on people I know. I have no right to other people’s stories. The exception is The Divorce Diet, which I wrote to make a friend laugh when her marriage was going down in flames and she was losing weight. But I had her permission to publish it, and the central character was based on her in only the loosest way – close enough for her to get the jokes; far enough away that I could write freely – and the people around the main character were purely (and carefully) fictional.

Inevitably, though, I draw from real people – this person’s energy or their impact when they enter a room; the way that person is in the world, or at least how they seem to me; some other person’s habit of, say, stroking a thumbnail. And the things that happen around me inform my sense of what’s possible, but none of it appears in my books in its raw form.

The ‘five stages of grief’ are alluded to in the opening line, and loss and sorrow run throughout the book. Was it always your intention to write a meditation on grief?

The book started with loss and sorrow, with Marge flat on the couch and watching the light change on the wall, so in that sense the answer is yes. But I had only the vaguest sense at that point where the story would take me, so I could say no with equal honesty.

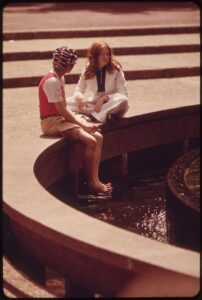

Oasis in the city: Block Square Park, Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

The novel is written from Marge’s point of view. Would Peg have given us a different narrative?

Interesting question, and one I’ve never asked myself. I expect Peg’s emphases would be different. Different moments would be pivotal for her, and she’d see the same ones from different angles. She’d interpret them differently. I don’t imagine the two versions would be in outright conflict, but without putting myself inside Peg’s awareness and telling the tale that way, I don’t know. As things stand, I know Peg only from the outside.

Marge carried out an act of violence in the early stages of their romance which haunted them over decades. Can you explain the guilt Marge continued to feel?

Marge feels not exactly responsible for what her violence led to, but does feel implicated in it. As she sees it, it grew directly out of the choices she made, even if she didn’t choose the result and couldn’t have foreseen it. (Sorry for being vague here, but I want to let anyone who hasn’t read the book come to it with an open mind.) If Marge were offered absolution, she’d turn it down. Guilt is a debt she owes and she intends to honour it.

It’s a place where I think Peg would tell the story differently…

Marge and Peg’s long relationship leaves Marge somewhat untethered when Peg is no longer around. Loneliness is another strong element running throughout the novel. Tell us about the core themes you set out to convey.

I didn’t really set out to convey themes. I found them as the story unrolled, and loneliness is definitely one of them. Marge doesn’t take her welcome in the world for granted, so loneliness is her default setting. Other central themes are grief – both for those we love and, surprisingly, for those we don’t – and family, with all its power and difficulty. At its heart, though, the novel’s about love. Not the perfect love of romances, but real, difficult, everyday love. Hard-earned love, not just for a partner but also for family and for children.

A number of issues that in another book might have been themes are background here: the relationship being between two women; class; the women’s liberation and the gay and lesbian liberation movements of the seventies. They inform the story, but they’re not the focus.

Family dynamics are strongly represented, particularly between mothers and daughters. Do you feel more comfortable writing female characters?

I’m drawn to women characters in large part because it’s as a woman that I’ve experienced life, but also because women – at least women with any depth – are wildly under-represented in fiction, and because women are just plain interesting. But I wrote part of Open Line from a man’s point of view and found myself comfortable in it. I don’t think I’d have a problem writing a book from a man’s point of view, but to date I haven’t been particularly drawn to the idea.

The title Other People Manage is both provocative and consoling. Was that your intention?

Confession: It wasn’t my original title, it was the publisher’s suggestion, and it’s much better than the original. Thanks, Mark.

If that’s the impact it has, I’m happy with that, but I find it disturbing as well as provocative and comforting. All three of those feel right. We grow up on tales of success, of romance, of triumph, and they leave us comparing ourselves to illusions and wondering why we don’t measure up. And yet, other people do manage – for the most part as imperfectly as we do.

I get to know my characters the way I get to know my friends, by seeing what they do and hearing what they say. The difference is that I sometimes have access to what they feel and think.”

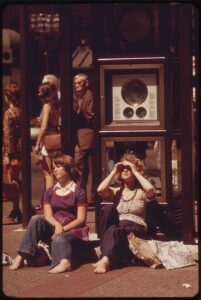

Block Square Park, Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

Marge, Peg, Rose, Jude, Deena and Krys are distinctive, beautifully defined people. Can you tell us about your process in creating all your characters? Do you create a backstory first, or let them loose in their worlds to see what transpires?

My characters usually define themselves as the story plays out. I used to teach fiction-writing classes, and some of my students had been bitten by how-to books that told them to create a backstory for their characters, or to interview them. I’ve never done either and I can’t think of more dismal ways to work – although if they work for someone else I won’t argue. It’s for myself that I hate them. What works for one writer will be a disaster for another.

I get to know my characters the way I get to know my friends, by seeing what they do and hearing what they say. The difference is that I sometimes have access to what they feel and think, but even there I generally have to wait until a scene comes together before I know their response. When I push them to do or feel something that doesn’t fit, the energy drains out of the writing and I have to go back and try again.

Megan is a troubled and disturbing character. Tell us about shaping her character and story arc in particular.

I’ve been around – at a distance, fortunately – several people who refused to let go of a relationship or to acknowledge that it had never existed, and at least one was an otherwise likeable person, not someone who set off any warning bells when I met him. Inevitably, I drew on my experience of them in imagining Megan, although her story is more extreme than any of theirs. I’m not sure why, but sexual obsession seems to be a powerful, recurring them in our culture. It’s never been the side of the story I care about. I’m less interested in what drives Megan than I am in the way Marge and Peg get sucked into the tornado around her, and the way that changes their lives.

Peg’s mother Rose is fierce with her daughters. She’s also very funny. Peg describes her as a woman who relinquished her ‘mommy routine’ and as someone who has enough unhappiness for everyone. Tell us more about Rose and the impact of her ways on her daughters.

For all her failings, I like Rose. I like that she’s funny and I like that you’d know where you stand with her. But she wouldn’t be an easy mother to have, in part because she did abdicate when her kids needed her and in part because she doesn’t hold back any part of herself to give them space. But for all her failings, she does love her daughters. Love is imperfect. Parents are imperfect. We’re all a mass of contradictions, and most of us do the best we can in difficult situations.

Rose’s abdication replays in a more extreme form when Deena abandons her kids, and it plays out in Jude’s dedication to her family – and in what I’d see as a tendency to hold them too tightly.

Weather station, Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

There are poignant scenes throughout the novel – from Peg and Marge getting to know each other by sharing stories of parental loss, Deena’s desperation, Marge finally letting go of the clothes in Peg’s closet. I’m curious to learn about how your own experiences have informed such highly skilled, deeply moving moments.

Again, my own story hasn’t poured into it in any obvious way. My parents lived into their nineties and were as likely to abdicate responsibility as they were to flap their arms and fly. My partner and I have been together for 45 years and last time I checked we were both still alive. In multiple ways, my life has been lucky. But eventually my parents did die, and even though it’s easier to accept when a person’s old, loss is still loss. And I’ve lived through the suicides of two close friends. I know what grief feels like. And guilt, for that matter. Those deaths left me with an awareness of how fragile life is, and the gaps people leave behind. My partner and I have also been spare adults in the lives of a number of kids, and that’s taught me how powerful – not to mention exhausting – the relationship is.

Why did you choose to set your novel in Minnesota?

I lived in Minnesota for forty long years (the weather’s brutal and I never did make peace with that), and it was the only place I could possibly have set it. The Women’s Coffee House was real. The bus routes, the Southdale Mall and the streets are real. The neighbourhoods aren’t named in the book, but I could walk you through them. I could take you to one or two of the buildings and to the place where another used to be. Some stories grow out of particular patches of soil and can only happen there. This, for me at least, is one of them.

How different have you found the US and UK publishing industries?

I can only talk about my experience. How typical it is, I don’t know. With Swift Press, I was allowed deeper into the publishing process than I’ve been able to go before, helping to shape the cover copy and the summary of a book that’s a bear to summarise. Swift has been an absolute dream to work with. But I don’t know if it’s fair to generalise from that. As far as submissions and agents and slush piles go, they work pretty much the same way on both sides of the Atlantic.

There is no universal measure of good writing. If one agent or press turns you down, or if fifty do, another may love it. If one reader hates your book, it may be exactly what another one needs in their life.”

What have you learnt about the publishing process that would be useful to share with writers without agents?

Having an agent is great but it doesn’t solve everything. Publishing’s still a tough business. Let me walk you through my experience:

I sold Trip Sheets, unagented, to a small literary press. I had an agent for Open Line and it also sold to a small literary press – one that I could have submitted to without an agent. I don’t say that as criticism of the agent. She was wonderful and stood by the novel through multiple rejections from larger houses. Agents can knock on doors that writers can’t reach, but they can’t force them open.

Waiting for the bus at Nicollet Mall, Minneapolis by Donald Emmerich, 1973. National Archives at College Park/Wikimedia Commons

When I sent The Divorce Diet to my agent, she wasn’t in love with it, possibly because it was more commercial than literary. I found another agent. (I was reasonably well connected in the writing community then and had a referral. That can get you read, although it doesn’t guarantee that you get accepted.)

That agent also stood by the novel through many rejections, finally placing it with a large, commercial independent publisher.

I tried both agents when I was ready to send out Other People. One was in the process of retiring and the other liked it and predicted that someone else would take it, but she wasn’t super-charged about it and, she said, you have to be to sell a novel these days. I’d have sent it to the press that brought out Open Line, but the editor/publisher had left and they hadn’t yet hired a replacement. That left me sending out endless queries, most of which got ignored, and led me eventually, still unagented, to Swift Press.

The advantages of a small press are that they’re open to newcomers and to writers whose previous books haven’t sold massively; that some of them have fabulous editors; and that they’re more likely to commit to the books they publish, because they can’t afford not to. The disadvantages are that not all of them have a long reach, although a few do, and that they can’t pay large advances. Having published The Divorce Diet with a larger, more commercial press where it didn’t do particularly well, I’m grateful to be back with a small press. Nothing’s guaranteed – did I mention that publishing’s a tough business? – but they’re doing what they can.

So by way of advice for unagented writers, let me say something most writers already know but that’s easy to forget when it comes to our own work: there is no universal measure of good writing. If one agent or press turns you down, or if fifty do, another may love it. If one reader hates your book, it may be exactly what another one needs in their life. Having a manuscript come close can be harder than having it overlooked completely, but it’s still only one person’s opinion, not everyone’s.

You do need a good piece of writing (by whatever standard) to start with, but after that a lot of luck is involved. I was lucky enough to try Swift Press, and to have them see possibilities in my manuscript, but the odds of being lucky increase if you’re relentless about sending out your work. The more hands it passes through, the greater the chances of it finding the right pair.

What are you working on next?

Swift has already accepted a second novel, which explores what happened to the American Left. I have no idea what the title will be. Let’s say that’s still in negotiations. In the meantime, I’m working on a novel that’s too new for me to say much about it – I’m not sure it’ll pan out – and I have a couple of non-fiction projects that are close to completion, one about moving to Britain and the other about English history.

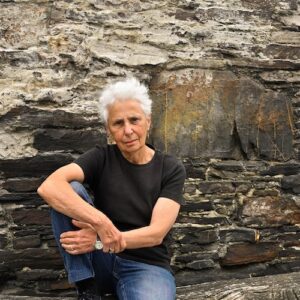

Ellen Hawley has worked as an editor and copy editor, a talk-show host, a cab driver, a waitress, a janitor, an assembler, a file clerk and, for four panic-filled hours, a receptionist. She has also taught creative writing. She was born and raised in New York, lived in Minnesota for many long, cold winters, and now lives in Cornwall. Other People Manage is published by Swift Press in hardback and eBook.

Ellen Hawley has worked as an editor and copy editor, a talk-show host, a cab driver, a waitress, a janitor, an assembler, a file clerk and, for four panic-filled hours, a receptionist. She has also taught creative writing. She was born and raised in New York, lived in Minnesota for many long, cold winters, and now lives in Cornwall. Other People Manage is published by Swift Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@ellen_hawley

@_SwiftPress

Author portrait © Ida Swearingen

Farhana Gani is a freelance writer, a book scout for Red Production Company and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@farhanagani11

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/farhana