Fatima Bhutto: Culture shifts

by Mark ReynoldsIn New Kings of the World, with customary wit and insight, Fatima Bhutto investigates how Bollywood, Turkish soap operas and K-pop are leading an emerging cultural movement that represents the biggest challenge to America’s monopoly on soft power since the end of the Second World War. The film below touches on some of the main themes, along with an update on her recent novel The Runaways, and is followed by a full transcript of our conversation.

MR: So America’s is no longer the only dominant pop culture, and unlike its flashy, liberal values that appeal to elites and the rising middle classes, the emerging genres have a broad appeal among the masses….

FB: American pop culture still exists in a massive and overwhelming form, but I think it speaks to less people today than ever before. Essentially the betrayal of globalisation, which promised the world a future of untold access, opportunity and riches, turned out to be a lie. The people who had access and opportunity and untold riches were the people who always had them, and everyone else found themselves unmoored. Hundreds of millions of people move from rural areas to the big city and find themselves abandoned, with no structure, with no help. And I think for the many hundreds of millions of people whose boats did not rise on the tide of neo-liberal reform and globalisation, American soft power means nothing. It doesn’t speak to your experience, it doesn’t speak to your suffering, to your failing, to your dreams and aspirations. In fact it becomes almost offensive to those failings and dreams and aspirations, because it’s so alien. But what do speak to you are Turkish cultural products, Indian films, Korean music, because those are still rooted in a world based on a traditional morality, coming to modernity and negotiating those changes. The storylines are more familiar, and what came up over and over again in my research is that people are hungry for storylines that reflect their own experiences.

Most of the migration in the world today isn’t international, it’s people moving within their own countries from rural to urban spaces. And urban spaces unfortunately have no mechanism to absorb all those people.”

You point out that those people newly arrived in cities from conservative, rural areas are often shocked by the depravity of the city and look for entertainments that match their own values…

That’s it, if you come to any big city, if you’re driving through Karachi you will see enormous billboards selling Magnum ice cream that even to me look sometimes jarring and out of place. What does that look like to somebody who’s come from a village where the population all know each other, where their families know each other, where if there’s a problem you rely on each other? How do you survive in a place where there is no support, but also the alienation of all big cities? And I think that’s true whether we look at Karachi or Bombay, or London or New York. Most of the migration in the world today isn’t international, most of it’s internal, it’s people moving within their own countries from rural to urban spaces. And urban spaces unfortunately have no mechanism to absorb all those people, to care for all those people, to support all those people, and to guide those people. And we see that in a lot of displays of anger, in a lot of rage, in a lot of fear. Things like Trump’s America speak a lot to the fear of this new world. You might even say Brexit Britain speaks to that.

You begin with Bollywood, and quickly assert that its tropes are “no more absurd than Hollywood’s”. Now that might not chime with Western prejudices, so could you explain why it is so?

I think we make fun of Bollywood quite easily, and we all have a shorthand for the joke, which is that there’s a dance number in a Bollywood film every ten minutes, at a very serious occasion there’ll be a musical interlude where people come back from the brink of death. And we joke about this, but the truth is that Hollywood has its own absurdities. In any Hollywood movie involving the CIA or the FBI, you’ll notice that the CIA director is always an adorable, kind and compassionate man who cries at the news of drone strikes, you know, the President weeps at the sound of war. Americans are always battling, but on the side of good. And they are always triumphant against their enemies, who never seem to change. We had decades of the Soviet menace, now decades of the Muslim menace, and it is absurd. One of the examples I give is Zero Dark Thirty, where you have a quite brutal torture scene where a man is being waterboarded, and the gaze of the camera is not on the man being tortured to within an inch of his life, but on Jessica Chastain the FBI agent, shivering in the corner because she’s so disturbed by torture she can barely stand straight. To me that’s absurd, but I think we’re so entranced by Hollywood, and we’ve been conditioned in Hollywood’s tropes and mores, that we come to it quite innocently. But of course no cultural production is innocent. Within it is politics that’s coded in a certain way, within it are a society’s leanings. So many things are written into culture.

Today’s Bollywood I find pretty thoughtless. The heroes are not dalits, they are not minorities. Women in Bollywood films are revered, but denied expression. They are always victims, and they never have any agency.”

So what do you love about Bollywood, and which aspects could you perhaps live without?

I have to confess that I am not a big fan of Bollywood – I know this is sacrilege to say. But I find Bollywood’s older movies quite interesting because they reflect in a very strong way the passage of time and of history, not just in India but in the subcontinent. So if you watch the movies of the 1970s or 80s, they’ve got very strong components of injustice. The hero is a man who is downtrodden, but honourable and noble, and has to fight insurmountable odds just to recover dignity, and there is something moving about that, but also something that’s easy to get behind, and to ignore all the kitsch. Today’s Bollywood I find… ah, well I would say I find it pretty thoughtless, and I think in its thoughtlessness it’s dangerous. So the heroes of Bollywood films today are not dalits, they are not minorities. Women in Bollywood films are revered, but denied expression. They are always victims, and they never have any agency. Agency is always delivered in tokenistic symbols and signs, but I don’t see them pushing against society. I see Bollywood film as the wholehearted acceptance of whatever society is today. And I find that worrying, as an audience member.

Do you think Shah Rukh Khan might disagree with that assessment? Because he has taken on roles in films that do sometimes challenge themes of identity and being an outsider.

© Fox Star Studios, Dharma Productions and Red Chillies Entertainment Watch the trailer

Certainly there are Bollywood films that have challenged concepts like identity. Shah Rukh Khan’s My Name Is Khan is an example of that. In the post-9/11 era, to make a film about a Muslim migrant to America who suffers racial stereotyping and abuse, that was I think unusual for its time, and important for its time. But the Bollywood movies of today are just bold-faced government propaganda. The danger is there’s a lot of war films, there’s a lot of films glorifying violence, and that violence comes at the behest of a movement. And I find that uncomfortable, I find it hard to watch Bollywood today much more than ever before.

You spent some time with Shah Rukh Khan in Dubai and Abu Dhabi when he flew out to participate in a prank TV show. Could you say a little about that episode?

New Kings of the World begins with the story of Bollywood, the history of Bollywood, and then I went to Dubai and Abu Dhabi to observe Shah Rukh Khan, who is the biggest star in Bollywood, as he filmed an Egyptian prank show for a Middle Eastern television channel. So it was this perfect example of global culture and the ways in which these different strains come together today. It was a ridiculous prank show. Anyone who has seen it will know that it involves swamps, lizards, drowning, death-defying stunts, and it was fascinating to watch. But also to watch the reaction of a film crew that was made up essentially of Middle Eastern men – of Lebanese and Moroccan, Tunisian and Egyptian men – to an Indian star. And they had the very clear sense that Shah Rukh Khan was their own. They didn’t see him as a foreign star, they didn’t see him as an international commodity, they identified themselves very strongly with him, and I wasn’t really prepared for that, that was unusual to see.

You point out that Khan is a Muslim superstar in a country run by Hindu nationalists, as well as an icon of neo-liberal capitalism. Does it bother you at all that he’s played Muslim characters in only a handful of his films?

In Shah Rukh Khan’s career he’s played many different roles: from soldier to busker, to angel, to superhero – quite a varied list! He’s only played Muslim characters six times, I believe, and two of those were cameos. But that’s not unique to Shah Rukh Khan. The heroes of Bollywood films are not Muslims, just like they’re not dalits or members of the tribal community, or farmers, or children who are abandoned to lives on the footpath. Bollywood is an industry at the moment that celebrates wealth and power, and I think that’s true for all its characters. Just thinking of the last ten years, they mainly work in multinational corporations in London, or they travel to Lisbon, they have these borderless lives which don’t really reflect the world as it is today. I would say, however, that Indian television, which is not as old an industry as Bollywood, if we’re talking about streaming and shows on Netflix or Amazon Prime, they are more interesting than Bollywood because, for all their faults, I think they’re trying to expand a little bit more about what a main character can be. And they’re trying, in whatever way that they’re trying, to touch issues that you wouldn’t see in Bollywood film, issues like sexuality or homosexuality, or abuse that goes on in families. That is new, so I’m watching that with some interest at the moment.

In the 1970s and 80s, under the darkest period of dictatorship that Pakistan has ever faced, you had great movements of resistance against that oppression that came through not just theatre, poetry, music, art, but a lot in television.”

Of course there has always been more to Indian cinema than just Bollywood, from Mehboob Khan and Satyajit Ray to Deepa Mehta and Mira Nair. Which non-Bollywood filmmakers are making an international impact today?

One of the great cultural products which is little known outside today actually doesn’t come from India at all. Pakistani television dramas are very popular in South Asia, and they have been very popular in the West Indies and England, and in far-out parts of the world over the years. But Pakistani theatre and Pakistani television dramas have a quite rich history. In the 1970s and 80s, under the darkest period of dictatorship that Pakistan has ever faced, when CIA-backed dictator General Zia-ul-Haq essentially brutalised Pakistani society, censoring the media, prescribing amputations as a punishment for theft, you had great movements of resistance against that oppression that came through not just theatre, poetry, music, art, but a lot in television. And those dramas were very nuanced, they were written in a very classical, beautiful Urdu, they had a limited number of episodes – ten or twenty episodes – and they tackled not just the political system but the social systems and the social ills of Pakistan. And actually if we’re looking for sophisticated art forms that have a powerful political centre, I’d say it would come from Pakistan.

Does that translate into cinematic releases as well?

Not so much in the 70s and 80s. In the early 2000s up to today, Pakistan has started to produce more films, but they’re not cut from the same cloth. There were some famous early attempts, after 9/11 again, that addressed the issue of being Muslim abroad, the idea of stereotyping, but otherwise I would say that Pakistani films or cinematic products are still in their early days. They are always producing new things, they’re bringing in talented young directors, but it doesn’t quite have the same history that the TV dramas do.

The Turkish soaps you describe were a new phenomenon to me, and I’m not aware of any of them having been broadcast in the US or the UK, so I was intrigued to see that the English-subtitled opening episode of Magnificent Century has 6 million views on YouTube. So what are the largest – and most surprising – territories the Turkish soaps have conquered?

Today Turkish television dramas, or dizi as they’re called, are second only to the Americans in worldwide television distribution, and the Anglo-Saxon, English-speaking world is the one part they haven’t quite penetrated yet. However, they’re incredibly popular all across Asia. The Turkish wave began in the Middle East, and it went from the Middle East to South Asia, they’re very popular in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh. It’s incredibly popular in Eastern Europe, actually, and it’s massive in South America. Spanish television bought several shows, they broadcast at primetime and have more viewership than American shows like Modern Family or The Big Bang Theory. And they are on Netflix and Amazon Prime and things like that, so you can watch them with English subtitles.

It’s fair to say that President Erdoğan has mixed feelings about Magnificent Century’s portrayal of a powerful but liberal Ottoman Empire. Can you say a little about the Turkish state’s response to the show…

Magnificent Century is of course the most popular, the most famous Turkish dizi, and it’s the story of Sultan Suleiman and the expansion of the Ottoman Empire to the point where it reaches the doors of Vienna but is pushed back. And though this was an international hit – its distributors estimate that upwards of 500 million people in the world have seen it – Erdoğan’s government were not big fans of the show. They found it a bit racy and risqué, there was a bit too much of the love story, not enough of the glory and honour – though there was a lot of that. The most popular dizi today is a show called Ertuğrul, which is a story of the last Ottoman emperor, who was then unseated by the Young Turks. That has, if not the guidance of Erdoğan’s government, certainly its blessings, and it’s a phenomenally popular soap. So this is the Turkish state’s narrative, but it’s done in an incredibly watchable, engaging way.

Soft power relies on a certain believability. However brutal or unfair American power was, even when it had a soft cover like Obama or Clinton, it was still seen as believable. That story is much harder when Trump is the face of that power.”

Of course the past glory and subsequent demise of the Ottomans offers a clear warning to the geopoitical powers of today and tomorrow. So is the American Century well and truly over?

I don’t think we could put an expiration date on the American Century and say today it’s dead in the water, no, but I it’s never been so weak. This is the first time it’s faced serious challenges to its hegemony. If you go to Turkey or you go to India, Hollywood movies are not the first at the box office, local movies are. I think soft power relies on a certain believability. However brutal or unfair American power was, even when it had a soft cover like Obama, or let’s say even the Clinton years for some, it was still seen as believable. When you watched a film about the good old American soldier out to save the world, you could believe it. That story is much harder when Trump is the face of that power, when Mike Pence is the face of that power, that’s a harder sell. That doesn’t mean that India or Turkey or Korea are innocent powers with no agendas; but our exposure to those agendas is fairly new, if we’re looking at an international audience.

Which other countries outside the scope of this book are also becoming more of a cultural influence in recent years?

There are so many countries whose cultural products are not just fascinating but have far-reaching implications who I sadly couldn’t fit into the book. I think if we look at Nigeria, Nollywood is making amazing strides in the world of streaming; they have massive viewership online, there are many Netflix-type portals that pull in huge numbers of people, not just in Nigeria but across Africa. If you’re looking at sophisticated cultural products, then you can’t have a conversation without Iran. If we’re talking about music, that comes from not just places like Korea but the Chinese are moving ahead. The head of Warner Bros Music said already, several years ago, that people will want to break into China the way they once wanted to break into America. So I would say the Chinese are certainly one to watch; I think they’re going to be an enormous force in global culture. Certainly we already feel their imprint today, but I think that’s going to grow and it’s going to change the way the model works. But the truth is, it’s happening everywhere, there are lots of micro little explosions, there is no centre anymore. We live in a multipolar world, and culture reflects that.

Turning to K-pop, Psy’s 2012 ‘Gangnam Style’ video has racked up 3.4 billion views on YouTube. In many ways it should be indecipherable to non-Koreans, yet everybody still sings along and does the silly dance, and Ban Ki-Moon even hailed it as “a force for world peace.” You write that, “For the uninitiated, K-pop sounds like something you’ve heard, and vaguely liked, before… EDM earworm pop [that is] genuinely catchy and happy.” It’s a perfect example of ‘glocalization’…

K-pop is fascinating, and one has to separate ‘Gangnam Style’ from K-pop, because Psy is not considered a product of the K-pop system, which is incredibly regimented and run the way a multi-billion-dollar corporation is, not an artistic industry. Korean, unlike Japanese or Mandarin, is a syllabic language, that’s why it’s very easy for us English speakers to sing along with it. And it follows the general trend of glocalisation, which is what a lot of K-pop is built on, which is to take music we know – Western pop and dance music – and to speed it up so it’s at a slightly faster pitch, and that makes it dancier, it makes it more energetic. K-pop wasn’t born by accident, it comes out of the Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s, and Korea’s incredible innovation, which was to understand that it would be at the mercy of economic forces if it relied on heavy industry, but inspired by Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s theatre productions and Hollywood films, the then president of Korea thought that if you had time, and you had talent, you could build something enormous that would not be so vulnerable to market fluctuations. And that’s what they did, they poured millions and millions and millions of dollars into the cultural industries, into film, into television shows, into video games and into music.

While Hollywood takes its sweet time putting people who come from non-white backgrounds into films, the truth is we’re watching other stuff already.”

‘Gangnam Style’ is actually only the sixth most viewed video on YouTube. In top spot is Puerto Rican singer Luis Fonsi’s ‘Despacito’ with an astounding 6.5 billion views. So Latin pop is a thing too…

Wherever we are in the world or whatever decade, we have sung along to Latin songs and Latin hits, whether it’s Buena Vista Social Club or Gypsy Kings or those one-hit wonders like ‘Macarena’. But what separates the Latin from the Korean is that Spanish is the most widely-spoken language in the world, it beats English, so there would be an enormous population receptive to Spanish-language music, whereas nobody speaks Korean except North and South Korea, and yet they’ve got people from Iran, Indonesia to America singing along to their music, so that’s what makes it a more curious phenomenon.

One thing that links this book with your fiction is that you’re championing sections of society that are generally misunderstood or misrepresented in Western media, and questioning the ideas and norms that the West has long imposed on the rest of the world. So what other themes and issues inspire you to write?

I’m always interested in the world that’s presented outside of the centre, whether I’m writing fiction or non-fiction. I always felt, growing up and even today as a an adult, that the Western centre doesn’t speak to many of us, even people like me who were educated in Western schools or speak and write and work in English. We have different centres, and those centres are never quite given the same light. So in my writing that’s always what I’m looking for, to move a bit of the light somewhere else, somewhere that to the rest of us isn’t dark, but may as well be. And it was very important with New Kings to do this somewhere like culture. Because we talk a lot about representation today when it comes to film, but what does representation mean? It’s not enough to see someone that looks like you in a film, it means something much more to see someone that struggles like you, someone whose language is yours, someone whose community is yours, someone whose shorthand is yours. And I don’t think we see that. And while Hollywood takes its sweet time putting people who come from non-white backgrounds into films, the truth is we’re watching other stuff already. It’s not enough for Hollywood to make a film where there’s a South Asian main character or there’s an African-American hero, because there are other industries where it’s not just the figure but the story, the plot, the scenery, that’s powered by different cultures, and we can just go there and watch those products.

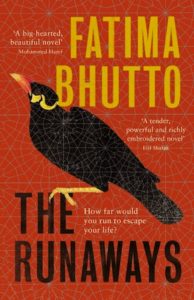

What’s been happening with The Runaways since first publication?

It’s been a really interesting experience, because it came out at a very politically charged time, when you did have the stories of many real-life young people who had run away to join radical groups like Daesh in Iraq and Syria, and that’s been very interesting to talk about alongside a novel, alongside a work of fiction, but I think it’s also made it quite uncomfortable. The Runaways doesn’t have an American publisher, because that’s not a conversation America wants to have. The stories of young Muslims who are displaced and alienated doesn’t have a lot of room in Trump’s America. And that’s surprising and unsurprising at the same time – especially for someone like me who has always drunk the Kool-Aid, and believed that we are supposed to talk about uncomfortable issues. But on the other hand it’s been really well received in England and Australia, it comes out in French next year, and it’s been really moving for me to meet a lot of young people all over the world who are not radicalised, but who understand how dangerous alienation is – because we feel it today, it’s a symptom of the modern world. How do you connect in a world that is supposed to foster connections, with all the technology we have, but actually it’s a very lonely place, especially if you don’t look or sound like you belong.

Can you imagine the book as a TV drama, and perhaps cracking America in that way?

I’m nervous of that, because I think a TV series would remove the nuance of the story. If we look at film or television shows that have been able to understand radicalism, and the violence that springs from radicalism, I can only think of one. There’s a very good French show called The Bureau, which to my mind is the most sophisticated understanding of terror and radicalisation, and how especially young Western people can be radicalised. But I don’t see that really in Hollywood. The Bodyguard in England didn’t do it for me, I have to say. There was another show called The Informer that I found really pretty offensive and kind of base. Homeland, 24, we know the American versions, and again they’ve traded on a simplicity that’s not just dangerous, but pretty ugly.

So what are you writing next?

I’m slightly depleted after the last two books because of the timing; it happened that they ended up overlapping a little bit. So I’m going to take a little break now, post-New Kings, and I don’t know if I’ll write another non-fiction or fiction yet, but hopefully I’ll have a quiet period to look for things that start to obsess me.

Fatima Bhutto was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1982 and grew up in Syria and Pakistan. She graduated from Barnard with a degree in Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures, and has a masters in South Asian Government and politics from SOAS. She is the author of five previous books of fiction and non-fiction, including her debut novel, The Shadow of the Crescent Moon (2013), which was longlisted for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, and the memoir about her father Murtaza Bhutto’s life and assassination, Songs of Blood and Sword (2010). Her second novel The Runaways was published in March 2019, and will be out in paperback in spring 2020. New Kings of the World is published in paperback by Columbia Global Reports.

Fatima Bhutto was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1982 and grew up in Syria and Pakistan. She graduated from Barnard with a degree in Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures, and has a masters in South Asian Government and politics from SOAS. She is the author of five previous books of fiction and non-fiction, including her debut novel, The Shadow of the Crescent Moon (2013), which was longlisted for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, and the memoir about her father Murtaza Bhutto’s life and assassination, Songs of Blood and Sword (2010). Her second novel The Runaways was published in March 2019, and will be out in paperback in spring 2020. New Kings of the World is published in paperback by Columbia Global Reports.

Read more

fatimabhutto.com.pk

@fbhutto

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista